A Monument Then and Now

Did the demolition of the greenfield (really the Beechwood Boulevard) Bridge feel like the passing of an era? The urbane, concrete arch span of 1923 was crumbling far too ominously above the speeding traffic of the Parkway East to be able to stay in place, so it was ceremoniously demolished. A replacement will be completed by September 2017, but today’s much stiffer concrete and less-resolute aesthetic tastes, at least in road construction, mean that no structure will be built exactly like that again.

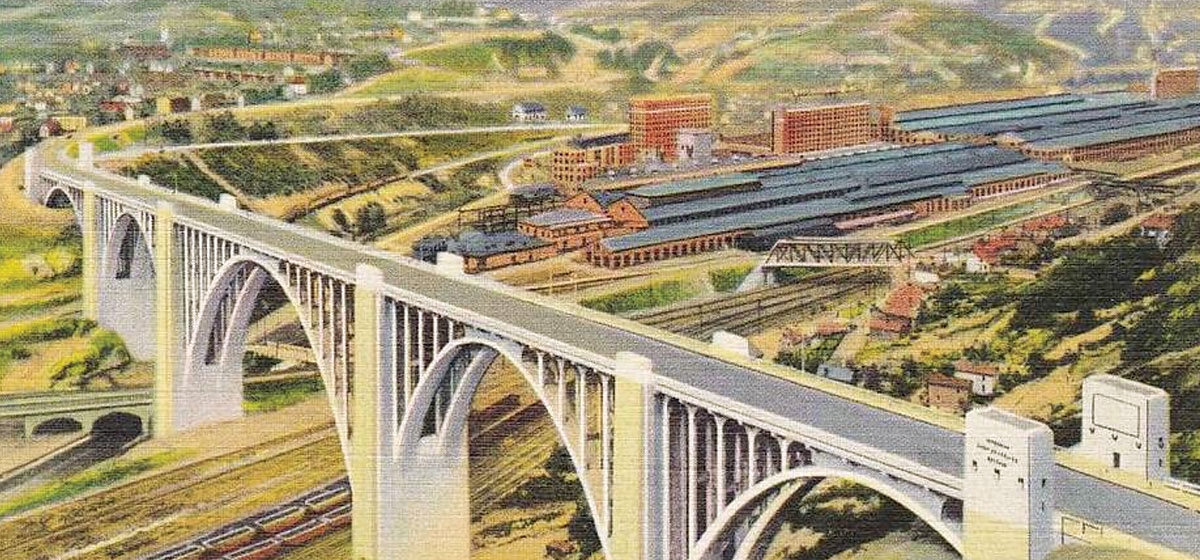

Yet, just a few miles away, the granddaddy of all 20th-century concrete spans, the George Westinghouse Bridge, is still with us, a great symbol of its era. Stretched dramatically over the Turtle Creek Valley between East Pittsburgh and North Versailles, the heroic concrete structure was considered a marvel of engineering when it was completed in 1932. It crosses 1,560 feet of the valley in a sequence of five arches, the largest of which rises 200 feet from the lowest point and spans 450 feet. When it opened, it was the largest such structure in America, and the second largest in the world.

Designed by George S. Richardson and built by Booth & Flinn Company, the Machine Age-style concrete construction with sculptural granite friezes atop its four outermost pylons might evoke the great achievements of the New Deal. In fact, Pittsburgh and Allegheny County had great bridgebuilding campaigns of the 1910s and ’20s. Car registrations increased tenfold in those decades, and roads had to keep pace.

The Lincoln Highway was no exception. It had been envisioned in 1912 as a cross-country road comprising largely existing routes. As the Philadelphia to Pittsburgh Turnpike (then Route 30), it had crossed through the Turtle Creek Valley in the early 19th century, but its early 20th century passage there seemed especially precarious and unpleasant. Cars wound down an alarming 9 percent grade through a thicket of streets and intersections, “the worst section of any road in the state,” opined the Post-Gazette in 1929.

Yet, the real congestion in the valley came from railroads and industry. The Pennsylvania Railroad first ran through in 1852. When Andrew Carnegie built his steel mill in adjacent Braddock in 1875, he famously named it for Pennsylvania Railroad President Edgar Thomson, for whom he quickly became the largest steel supplier. Other train lines—Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania & Lake Erie and Union Railroad—traversed the valley along the Monongahela. And George Westinghouse started moving his companies from Allegheny City to the burgeoning industrial nexus of the Turtle Creek Valley in 1889 to be near the Pennsylvania Railroad. In the process, he revolutionized railroad-related fields of safety, signaling and electrification.

Though we see the area as depressed brownfields today, the convergence of those three great industrial entities made this one of the world’s foremost manufacturing centers and infrastructural tangles. When the bridge went up, it wasn’t simply straightening and smoothing the automobile paths. It had several layers of transportation and industry to span and effectively culminate.

Supervising Engineer V.R. Covell explained in Scientific American, “One hundred ninety feet below the new bridge, the trains on the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad thunder past, crossed overhead by the Union Railroad, and underneath by a main highway carrying a street railway, and [finally] by the Turtle Creek.”

The transportation artery that would surmount all these others needed to be suitably monumental. The engineers considered numerous designs for the span, including a variety of steel cantilevers. Yet, regardless of the valley’s defining industries, they decided that a concrete arch structure would be most suitably monumental and grand. Concrete gave the hint of historic architecture and the cultural authority of the millennia. As Westinghouse chief A.W. Robertson declared on dedication day: “Noble arches will ever be a symbol of man’s conquest over nature… a symbol of man’s God-given ability to control and shape his environment to his advantage.”

The bridge that seemed simply like a culminating achievement in that moment looks in hindsight like a very different era simultaneously. While cars dashed over concrete superstructure to the suburbs, factories served by railroads continued to form the core of industrial towns and cities. No longer satisfied to go through or around, the automobiles of the 20th century drove above the industry of the 19th. Architectural historian Martin Aurand discusses this relationship and the view from the bridges and trains through the valley in an excellent book, “The Spectator and the Topographical City.”

Of course, much of the industry ultimately departed. Westinghouse Companies are gone from East Pittsburgh, with a few remaining industrial buildings available for rent in an industrial park. Though freight train traffic is brisk at 50 to 70 per day, passenger trains are down from a couple hundred a day to just a couple. The Edgar Thomson works persists with around 900 employees, down from a peak of 5,000, an isolated mill that once led an industrial region.

So, too, the George Westinghouse Bridge soldiers on. A major restoration in 1983 brought it back from a low point of poor maintenance and limited traffic. Addition of some unsympathetic Jersey barriers has not compromised its overall grandeur, even if the valley below gives cause for melancholy rather than celebration.

As we work to envision driverless cars and plan for the eventual end of fossil fuels, we experience a period of at least as much promise and tumult as that which greeted the Turtle Creek Valley in 1930. How to engage freeways and bridges in coming years? A great work of civic art gives sharp and lasting focus to moments of historic import in a way that a few new lanes, however wide and smooth, can never do.