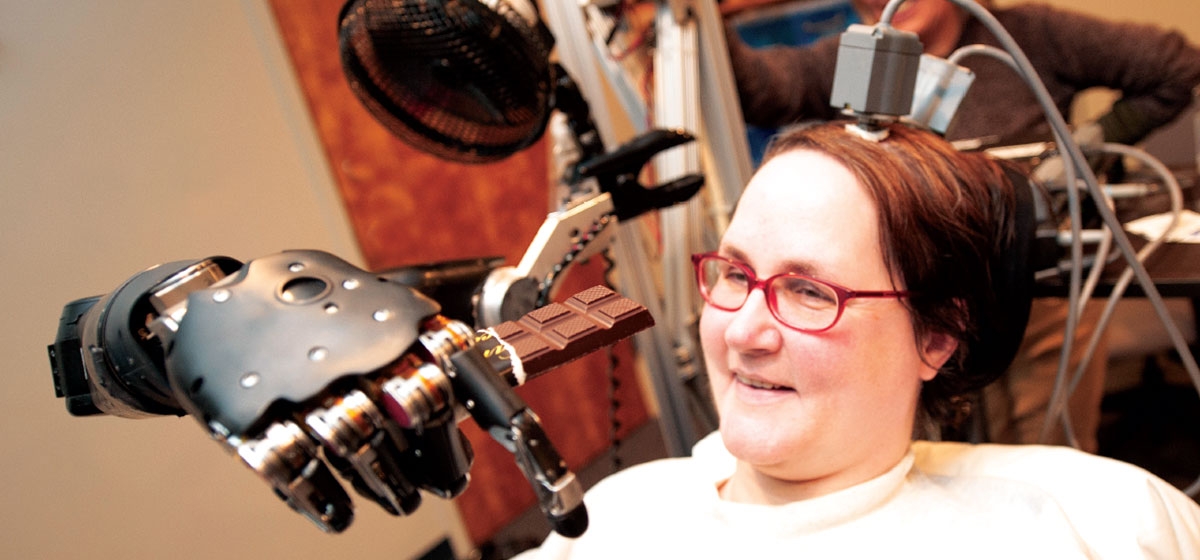

“Let me eat chocolate.”

That was quadriplegic Jan Scheuermann’s simple request when she committed to a trailblazing UPMC and Pitt School of Medicine study that would let her control a robotic arm with her mind.

“The doctors asked me: ‘What is your goal?’ ” Scheuermann recalled with a laugh. “I could tell they wanted to hear something profound. But I simply told them, ‘Heck, I want to feed myself chocolate.’ “

In February 2012, doctors surgically placed two quarter-inch square electrode grids in the regions of Scheuermann’s brain that would normally control right arm and hand movement. Ten months later, she fed herself a dark chocolate Dove bar as friends, family and doctors watched. She essentially moved the robotic arm with her thoughts. In April, the breakthrough was chosen to receive a Top 10 Clinical Research Achievement Award by the Clinical Research Forum.

“I was super excited,” said Scheuermann, who lives in Whitehall. “There was the excitement of reaching a goal, of accomplishing a task that could lead to so much more. And then, it was chocolate! I mean, come on.”

In 1996, Scheuermann was living in Lancaster, Calif., with her husband and two young children, running a business as a murder-mystery party host when her legs suddenly began to weaken. Soon, she could no longer drive her kids to school. Her legs and arms debilitated to the point that she needed a wheelchair and help with eating, bathing and dressing.

“The scariest part when it started was that no one could properly diagnose it. I thought I was going to die. All my family was back here in the Pittsburgh area, and I thought that if I died I didn’t want my kids alone out there without family. We moved back here.” Doctors diagnosed Scheuermann, now 53, with a genetic disease called spinocerebellar degeneration, and she gradually lost all motor function from the neck down. Before her illness, she stood 6 feet tall and was always bright and optimistic. A self-described “ham,” she exudes the same qualities these days. But after the disease set in, there were dark days.

“Of course, I was extremely depressed—there was a lot of crying for the first two years. I felt as if I was nothing.” She never contemplated suicide but said that therapy and antidepressant medication worked wonders. “Prozac gave me back my personality. I still get down once in a while but it is much easier for me to get out of it. When I get down, I tell myself to count my blessings. I have so much.”

Scheuermann, with the help of her attendant, Karina Palko, travels several times a week to Oakland for hours of testing with the robotic arm she affectionately named “Hector” (“Because it looked like a Hector,” she said. “No other reason.”) However, there’s also a believe-it-or-not coincidence behind the name. “We have since learned that ‘hector’ in Greek means ‘to grasp,’ ” she said. Doctors describe the work Scheuermann does with Hector as exhausting in every facet. But it’s given her new purpose and energy.

“She is an amazing person and she is amazingly upbeat,” said senior investigator Dr. Michael Boninger, professor and director of the UPMC Rehabilitation Institute. “She is not only a participant; she has become part of the team.”

Boninger estimates there are 100 doctors, engineers, technicians and others behind the technology known as brain-computer interface. They are studying Scheuermann’s brain signals to guide Hector. Specifically, the electrode points pick up signals from individual neurons, and computer algorithms are used to identify the firing patterns associated with particular observed or imagined movements, such as raising or lowering the arm, or turning the wrist As Boninger said, “The more that we can tap into the thought process, the more it has implications to help people with spinal cord injury or amputation.”

The emphasis is on the underlying idea of basic science—”not just putting together a bunch of machines and turning a switch on,” said Andrew Schwartz, a professor in the neurobiology department at Pitt’s School of Medicine. “The real excitement from my point of view is trying to understand something more about brain function. That is where the real payoff is going to be. The technology has enormous potential.”

Scheuermann embraced the project, which is entering its 16th month, after viewing a video of a similar UPMC and Pitt study involving a Butler man.

“I’m just having a blast,” she said. “But I feel like it’s the team who has done all the work. It’s like they spent all these years building up a terrific, souped-up car and now, at the last minute, I come in and I get to drive it and I get all the attention. It doesn’t seem fair. I understand that I am the human face of it, but the work behind this is incredible.”

She’s been interviewed by reporters from all over the world and recently appeared on “60 Minutes.” In February, she shared her story with students at St. Elizabeth Elementary School in Baldwin, her childhood alma mater.

Her daughter, Elizabeth, 23, is beaming with pride. “This study has given her new life,” she said. “She was always a very helpful person and very able-bodied. Now she’s doing something that could very well help others immensely down the road. Because of that, our entire family is happier.”

The length of the study remains undetermined. Doctors recently applied for an extension and received approval, after Scheuermann’s first year of testing. But at some point the implants in her brain will have to be removed as studies progress with better technology.

The lists of possibilities are many: Doctors would like to be able to make the arm-like devices small enough for patients to be able to take them home. They would eventually like to implement wireless technology for the robotic-arm setup. There’s even the hope that a device could be combined with brain control to restore movement to someone’s own limb.

“I hope Mom will remain a figurehead and part of the study for many years because it gives her so much meaning in life and happiness,” Scheuermann’s daughter said.

When Scheuermann is not working with doctors and researchers, she is working on her second murder-mystery novel. Her first, “Sharp as a Cucumber, A Brenda La Voom Mystery” was released last summer and is available on Amazon.com.

“I just count my blessings,” she said. “I have all these good things in my life. My family loves me. I can’t whine. I know I can’t walk tomorrow. But, so what? I can’t think about being a quadriplegic for the rest of my life. But can I do it today? Yes.’ ”