Making Monopoly Illegal

When people who don’t like free markets (i.e., almost everybody in academia) talk about antitrust law, they almost always begin by saying something like this: “One of the core defects of market economies is the inevitability of monopolistic practices.”

Previously in this series: “The Tricks of the Trade: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part V”

These people seem not to have noticed that socialist economies consist of nothing but monopolies; the state owns everything and doesn’t tolerate competitors. More compellingly, if monopolistic practices are characteristic only of market economies, it’s curious, indeed, that antitrust laws predate the rise of the market economy by almost 2,000 years.

In 50 BC, during the Roman Republic, grain traders were slowing grain-carrying ships in order to create artificial shortages, thereby driving up prices. A law was passed imposing heavy fines on anyone caught engaging in this practice.

Later, in the early fourth century AD, Rome imposed the death penalty on anyone convicted of creating artificial scarcities of necessary, everyday goods. Later, in the fifth century, Rome passed laws providing penalties, including confiscation and even banishment, for anyone creating a monopoly. (That is, anyone other than the Roman state, which happily awarded monopolies to itself.)

In the Middle Ages in England (before the Norman conquest), traders would buy up goods and withhold them from the market until prices rose. As recorded in the Domesday Book, laws provided for forfeitures for anyone convicted of this practice.

On the Continent, similar laws were passed addressing practices that artificially raised prices, and under Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, laws were passed “to prevent losses resulting from monopolies.”

In the famous Dyer’s case in England (1414), two dyers had conspired not to compete with each other for a period of time. When one of the dyers ignored the agreement, the other sued to compel his performance. But Judge Hull was outraged by this obvious restraint of trade and refused to enforce the agreement, writing that, “per Dieu, if the plaintiff were here he should go to prison.”

Meanwhile, market economies didn’t arise until the latter part of the eighteenth century, and even then only in the United States, Britain and Western Europe. This type of economy was first noticed and described in 1776 by Adam Smith in “The Wealth of Nations,” 1,826 years after the Roman Republic passed its first antitrust laws.

The modern era of antitrust law began in the United States in 1890 with the passage of the Sherman Act and, haltingly, in Europe in 1923 when Germany enacted the first antitrust legislation on the continent. But Europe’s antitrust laws disappeared during the Great Depression and weren’t resurrected until, under American pressure following World War II, the UK and Germany enacted comprehensive antitrust legislation.

In the United States, antitrust laws were strengthened and broadened beyond the Sherman Act by the enactment in 1914 of the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act. Other laws addressing anti-competitive behavior, albeit with far lesser impact, include the Robinson-Patman Act (1936) and the Celler-Kefauver Act (1950).

The main actions U.S. laws have deemed to be anti-competitive include these:

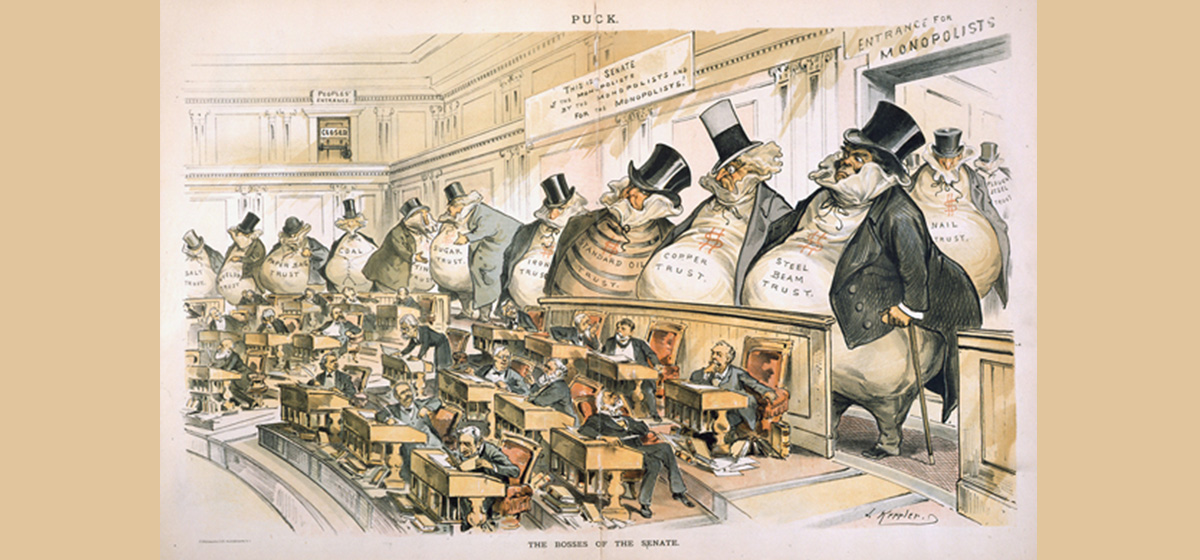

The Sherman Act: The Act arose out of concerns about the huge corporations that had arisen late in the Industrial Revolution and the real and perceived abuses of power these companies engaged in. Specifically, many companies had colluded with each other (forming “trusts” that the trust-busters wanted to bust) that gave them huge power over markets and prices. The Sherman Act prohibited such collusion. It also prohibited any conduct that monopolized or attempted to monopolize a market. Finally, the Act allowed private persons to sue for violations of the Act and demand treble damages.

The Clayton Act: The Clayton Act was passed because courts had interpreted the Sherman Act as not covering certain practices Congress deemed to be anti-competitive. In addition, corporations quickly realized that, instead of colluding with each other, which would violate the Sherman Act, they could simply merge and engage in the same conduct as one organization. (A company can’t “collude” with itself.) As a result, in the decades after the passage of the Sherman Act there was a wave of consolidation across American Industry, creating the very conditions the Act wished to prevent. The Clayton Act, inter alia, extended the Sherman Act to cover mergers and acquisitions that resulted in monopoly power.

The Federal Trade Commission Act: This law created the FTC and authorized it to prevent unfair methods of competition and various deceptive acts that were believed to harm consumers. Many antitrust enforcement actions are brought by the FTC, not the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department, adding a large dollop of confusion to the antitrust sector.

Speaking of confusion, outside the United States, antitrust law is a bit of a mess. The Treaty of Lisbon, adopted by the European Union, mostly mirrors U.S. antitrust law and authorizes the European Commission (the executive branch of the European Union) to enforce the law, much as the Justice Department and FTC do in the United States.

But after Brexit, the UK is no longer subject to the Treaty of Lisbon, and, therefore, inside the UK the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) will enforce UK antitrust laws while the European Commission will continue to enforce EU laws. Companies, including U.S. companies doing business in the UK and EU (even if the scale of their non-U.S. business is trivial), will therefore be subjected to three parallel investigations — United States, UK and EU — with potentially different and inconsistent outcomes in each jurisdiction.

Given that the main U.S. antitrust statute was passed in 1890 and that the next two most important laws are more than a century old, one might wonder whether it all makes any sense today. In fact, antitrust enforcement rarely made any sense from the very beginning, as we’ll see next week.

Next in this series: “The Weird Inconsistencies of Trust Busting: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part VII”