Lost and Found

Some days are memorable for obvious reasons: births, deaths, weddings and funerals. Occasionally, however, a day is noteworthy not for any dramatic event but for what you suddenly understand.

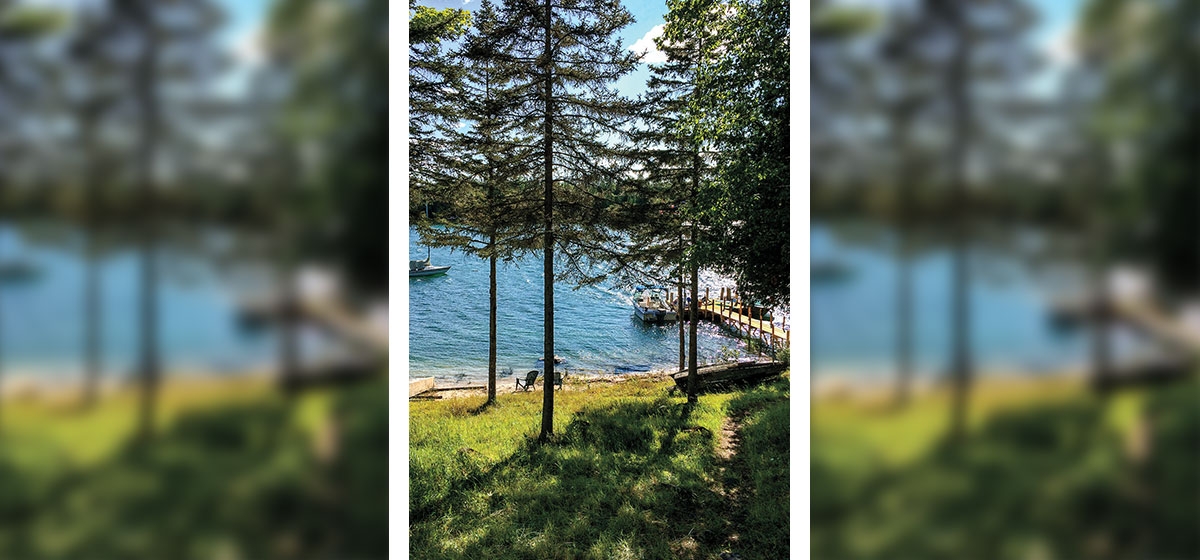

For 58 summers in a row, I’ve gone to a little town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula called Cedarville. What has turned out, in retrospect, to be the single most interesting day I’ve ever spent there began in a typical way 20 years ago. I drove the boat about three miles to my favorite spot, put out the anchor and started fishing.

At some point I noticed I was drifting and looked back to find the anchor and line gone. I hadn’t properly cleated it. Not a big deal—just an embarrassing little piece of negligence for a lifelong boater. At that spot, however, there’s a floating plastic milk bottle that someone tied to a weight, and it serves as a homemade rock marker. So that morning I tied my boat onto it and kept fishing.

Soon another boat appeared, and the other fisherman and I struck up a conversation across the water. I explained why I was tied to the rock marker. He turned out to be a local lawyer named Tom Evashevsky about whom I’d heard a lot of good things from a mutual close friend. We talked, fished, and the time flew, until I ultimately untied and said goodbye. As I drove home, I considered how just about everyone I knew in this little town had a kind of soft-spoken blend of modesty, integrity and wit that you couldn’t help but admire.

A couple hours later, when I went down to our dock, there was my anchor, with the line nicely coiled, sitting at the end of the dock. Whether by searching or luck, Tom had somehow found the anchor and taken the time to go miles out of his way and deliver it.

* * *

That afternoon, my old friend Jeb arrived with his wife and three kids for a visit. We unpacked their bags and went for a ride in my new used boat, and I told them, “This new boat has two gas gauges. One says it’s nearly empty and the other nearly full. If we run out of gas, we’ll know which one works.”

We were at Bosely’s Channel, a very narrow and beautiful waterway between two islands, when the motor sputtered, then conked, as they do when there’s no gas. We paddled 30 feet to the nearby boathouse, owned by some friends, and I asked Sam, our 10-year-old son, to see if he could find one of the Altmaiers and ask if they might have a tank of gas. I gave him directions because their house was a distance away, through a series of paths and roads. Off he went like a flash.

Some time later Sam appeared with Dale Dunn, a tall, strong man, with dark hair and dark tinted glasses. He was a local electrician who had married one of the Altmaiers and I knew him just well enough to say hi if I saw him in town, which was infrequent. He was carrying a red five-gallon plastic fuel container and something shiny. Everyone was happy to see him, and after I poured the gas into the tank, I thanked him and said, “I’ll just run down to Viking (the marina), fill this up and bring it right back.”

Dale shook his head and said, “You don’t need to do that.” But I said, “No Dale, we really appreciate it, and I definitely want to fill it up. I mean, that’s the least I could do.” And then in his slow, northern Michigan accent, he said “No, Doug. That’s not necessary.” I was about to protest when he raised his hand and said, “Maybe you’ll be able to help me some day.” How could I respond to that? I knew that was never going to happen, but there it was. So I just thanked him. And then Dale handed over the shiny item, which was tin foil over a big salmon filet he’d caught and cleaned that morning.

As we drove away, the others were chatting and smiling. I was thinking about the people in this remote little northern town. There had always been a tacit divide between many of the summer people and the locals. Historically, we came from big cities with purchasing power. And they worked taking care of our cottages, docks, and boats and selling us groceries, gas and wine.

That day, however, I realized there was a more profound divide. The locals had something essential that we had largely lost. In the city, we hustle, hurry and look after our own interests, the devil take the hindmost. In Cedarville, they look after each other. They go out of their way to help, if you need it. And they expect nothing in return. It’s simply their way of life, and it became obvious to me that day that theirs was simply better.

* * *

Jeb and his family ended up buying a summer place nearby, which they’ve enjoyed for years now. One day after Sam graduated from college, Jeb asked me for Sam’s contact info. Before long, Jeb had hired Sam to oversee his company’s Shanghai operations. It would be Sam’s first job out of college, and after it was a fait accompli, I asked Jeb why he’d thought of Sam.

“Well, you had told me Sam speaks Mandarin,” Jeb said. “But what really impressed me was that day when we came up to Michigan, and you ran out of gas. Sam jumped right out of the boat and ran off without a complaint—and he got the job done.”

The job with Jeb turned out to be a real launching pad for Sam. And of course it made me appreciate that day years ago even more.

Every summer in Cedarville has its events and rhythms. Some are memorable for years. Some just for a moment—like a sunset. Sometimes things go awry, and sometimes they come together, as if completing some previously inscrutable cycle.

Last summer I was out at Bosely’s Channel again, beyond the narrow passage where I’d run out of gas 20 years ago and in a bay on the big lake, as we call Lake Huron. There, floating in the shallows, was a very nice section of flotation dock—about 10 feet by 10 feet. It was just the kind of thing I’d been thinking of buying, but flotation docking is pricey.

This one had a line on it, and I waded out into the water and pulled it ashore. How it got there I had no idea—maybe it floated all the way across Lake Huron. I didn’t care. Under marine salvage law, if you find something like that adrift, it’s yours. And I would put this to good use.

The next day at the grocery I ran into David Altmaier, who lived across Bosley’s Channel. I mentioned I’d found this dock section and asked if it belonged to him. He said no, but then paused and cocked his head. “You know, Dale Dunn has been looking for a diving platform that fits that description. Somehow it got untied and he’s been looking all over for it.”

Back at the cottage, I hastily thumbed through the pages of the old phone directory. I punched in the number and waited for the old fashioned ringer on the other end. A familiar deep voice answered. “Dale,” I said. “It’s Doug Heuck.” I recalled to him that day 20 years ago and then said, “I was sure this day would never come, but today, I think I’m going to be able to help you.”