Let Us Now Heal Wounded Men

One thing, as men, that we rarely talk about, are the experiences we have suffered in the form of sexual abuse or trauma. The National Institute of Health found that 30.7 percent of men report having been the victims of sexual violence . . . and more than half of those before the age of 16. A 2014 study found that it takes on average about 20 years for a man to talk about his history of sexual maltreatment, because of the implicit stigma, coupled with our societal mores regarding masculinity.

The first time I was approached by a predator I was about seven; luckily my father was present and quickly dispatched the man. All I remember is a lot of shouting. There were other instances in my life that I’ve never spoken about — including the time I was attacked in a hotel bathroom as an adolescent, and even much later, as an adult working on Wall Street, when a C-level executive tried to use his elevated position to make a move on me – but in both cases I repelled the unwanted advances. And it has come out in recent years that the director of a summer camp I attended back in the 1970s was a predator. Luckily, I was not abused – my guess is that I didn’t respond to what I now recognize as grooming — but a fellow camper and friend from that period shared with me, over three decades later, that he had been violated by that man. It was a moving conversation, and a rare one, as I can attest from personal experience that men do not normally – or easily — speak about such things.

Thus, I suspect that a lot more men than we realize carry such stories silently, and if the “reported” number is 31 percent, then the actual number of victims impacted by such trauma is probably much higher. Could it be 40 percent? 50 percent? Or even more?

These memories and questions arose as I watched Barebones Productions’ performance of “Unreconciled” (2024), now playing at the company’s black box theater in Braddock. Based on the experiences of playwright and performer Jay Sefton (and co-written by Mark Basquill), this one-man show recounts Mr. Sefton’s torturous abuse by a Catholic priest in Philadelphia during his childhood.

The catalyst for this story couldn’t be more twistedly ironic: the molestations began when Mr. Sefton was cast in his 8th grade Catholic school Passion Play in the role of Jesus. Yet, to his credit, we come to this point slowly, after a good 30 minutes of background story generated by a collection of characters Mr. Sefton embodies, including his chain-smoking dad, multiple classmates, neighbors, nuns, and the priest who molested him, Father Smith. Mr. Sefton is a gifted actor and impressionist, and we see how these people in his past have so strongly shaped his present. However, this springs not from an evocation of resentment, or rage, as a more superficial retelling might have offered. These are Proustian re-embodiments, profusions of deeply buried sentiments filtered through the playwrights’ adult reconsideration of his childhood traumas. Thus, as an audience, we never feel manipulated, or awash in sentimentality. We are treated as sentient adults, and most important, as witnesses, watching a play, “Unreconciled,” wrapped around the story of the Passion Play, which ultimately masks the play in plain sight: a priest “acting” the false role of spiritual mentor to an unsuspecting 13-year-old boy, his family, and a pious community. It’s enough to turn one away from the Church, from the theater, and even from life, but Mr. Sefton’s character – and I would argue his soul — perseveres. Even through the extreme grief, and subsequent alcoholism that he recounts, but to which he never succumbs. In effect, Mr. Sefton – through his play — becomes his own redeemer.

Director Geraldine Hughes, herself an accomplished actor from Ireland, brings a thespian’s acuity to her ministrations of this drama. She allows the action to be delivered with a brutal tenderness that could easily have been smothered by a more tendentious hand — as if saying, we’ll get to all the bad stuff in due course, but let’s let the protagonist deliver the ugly along with the comic, which is how good storytellers operate. So, we also see some funny moments in the quotidian lives of these characters, which makes what happens much more real than if we only were shown the bad bits in a hyperbolic manner.

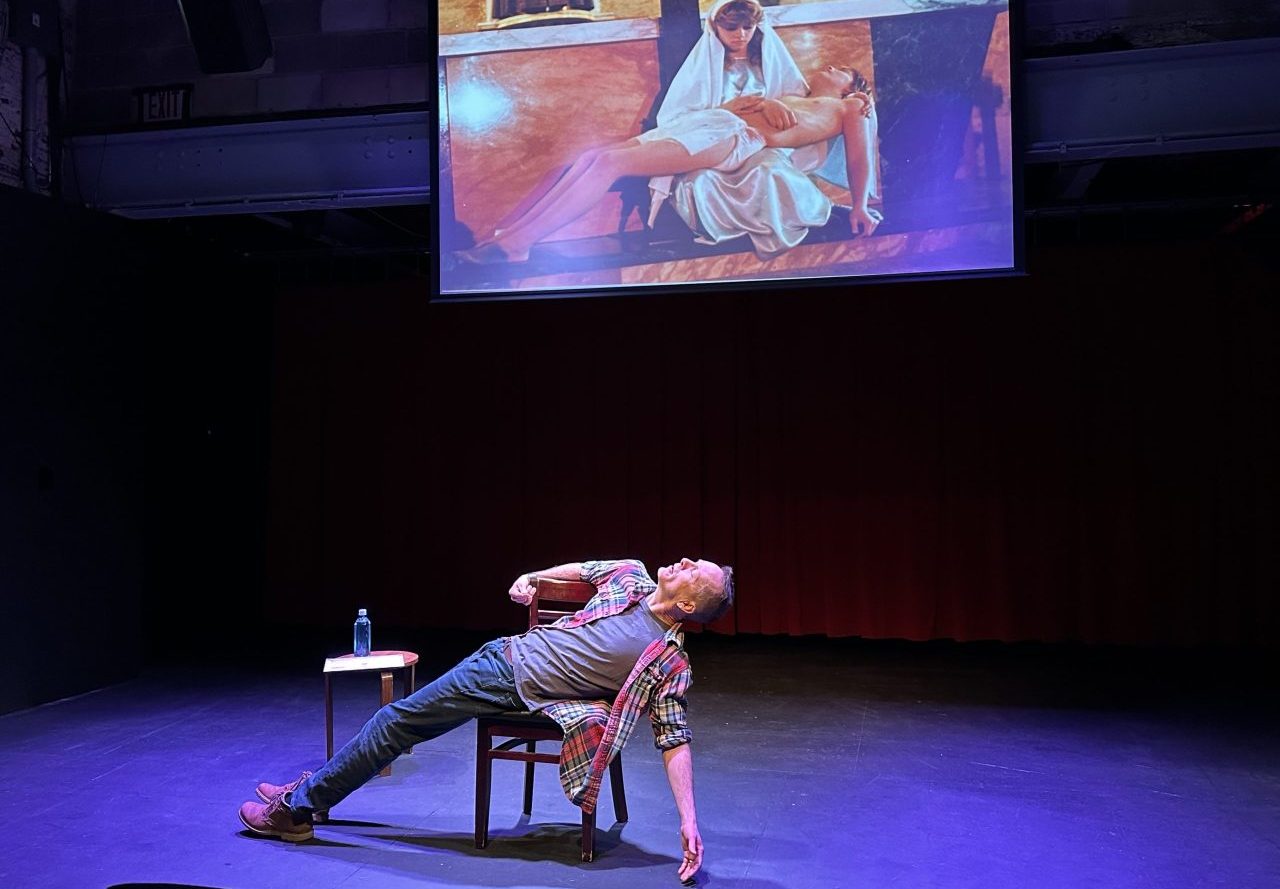

Adding to the intensity of the performance is the use of contemporaneous videos and photographs, where we actually see Mr. Sefton as a boy, playing Jesus, as well as on camping trips with Father Smith, where the abuse continued. One of the most striking images is of the young Mr. Sefton lying across the lap of Mary in the iconic pietà pose, suffering fictively as well as literally and, in addition, he recounts the teenage crush he had on the young woman holding him. It hits you on so many psychological levels and is, like all transcendent artistic acts, beyond simple explication.

This may be the barest Barebones production that you’ll see, as the set consists of one chair and a small table, on a completely unadorned stage. Looking back over Barebones’ last five offerings, it’s as if artistic director Patrick Jordan is whittling down his company’s productions to the most exiguous possible state of expression: casts of fewer and fewer actors dealing with bigger and bigger existential crises. There is a consistency here, a tableau spanning these shows – connected by vivid, contemporaneous playwrighting, a lack of histrionic embellishment, gritty acting, and even, most recently, by music. Sinéad O’Connor’s “Mandinka” ended the last presentation, while her “Emperor’s New Clothes” begins this one. Where can Barebones go from here? Only Samuel Beckett could guess.

Sitting on the table throughout the performance is an envelope, which turns out to be the Church’s “final determination” settlement offer, sent 33 years after the Passion Play in which the young Mr. Sefton played Jesus – notice the ironic symbolism of this number. I won’t reveal whether he accepts the offer or not; however, the title of this work may provide a slight clue. But what is crucial is how he reacts to it, and how, in the aikido moment of his last speech, emotionally cantilevered at the end of a raw, draining, funny, and profound 90 minutes, we get some closure, as painful as it might be. Projected over the stage, and especially compelling to a Pennsylvania audience, is the message that ours is one of about half the states that does not allow a “look-back” window for survivors to seek justice in the courts. Ultimately, what we do come away with is the stunning impact of this play, and a strong sense of redemption, even if that redemption is unreconciled.

UNRECONCILED continues through February 16th at the Barebones Black Box Theatre, 1211 Braddock Ave., Braddock, $40-50. www.barebonesproductions.com