Laissez-Faire vs. the Progressives

From the date of enactment of the first antitrust laws during the Roman Republic right up to the present moment, there have really been only three theories that have addressed the proper role of a government in controlling anticompetitive behavior.

Previously in this series: “Government Missteps: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part VIII”

Let’s take a quick look at each theory, in part because so much of what passes for antitrust opinion today seems to be completely ignorant of the past.

Laissez-Faire

After almost 2,000 years of laws dealing with monopolistic practices, philosophers and economists finally got around to thinking about what monopolies were, how they affected economies, and what, if anything, governments should do about them.

The first theory to be formed, the doctrine of laissez-faire, argued that governments shouldn’t attempt to control anticompetitive practices at all because those practices were inherently unstable and would collapse in the face competition from nimbler, more efficient competitors.

In other words, if a firm with a monopoly position raised prices, that would encourage the entry of new competitors who would charge less, thus undercutting the dominant firm and destroying its monopoly. Monopolists, according to the laissez-faire theory, become fat and happy and asleep-at-the-switch and are easy targets for smart new entrants.

Consider that most feared of monopolists, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. By 1875, Standard Oil controlled 90 percent of the market for the distribution and refining of Pennsylvania oil, which in turn represented more than 80 percent of all the oil produced in the world.

In 1890, the Sherman Act was adopted with Standard Oil specifically in mind. But in an ironic coincidence of timing, a year later the huge Spindletop gusher came in in Texas.

Although the Texas oil was thick and hard to refine (i.e., “sour,” unlike Pennsylvania oil, which is thinner and easier to refine, i.e., “sweet”) the sheer quantity of Texas oil spelled the end of the Pennsylvania boom and utterly destroyed the monopoly of Standard Oil. Exactly as predicted by the laissez-faire theory, Standard Oil was fat and happy in Pennsylvania and paid little attention to Texas until it was too late.

The laissez-faire theory was propounded by Adam Smith in the late eighteenth century, and was further elucidated by John Stuart Mill in his treatise “On Liberty” in 1859. Mill argued that free trade, without government interference even in the case of monopolies, was equivalent to individual liberty and thus “all restraint [by governments], qua restraint, is an evil.”

In 1942, Joseph Schumpeter further built the case for the laissez-faire position by arguing that capitalist economies are characterized by a “perennial gale of creative destruction” that prevents any monopoly from persisting. (Yes, that’s where the phrase “creative destruction” originated.)

Finally, under the influence of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, future Fed Chair Alan Greenspan also backed the laissez-faire approach to monopolistic activities.

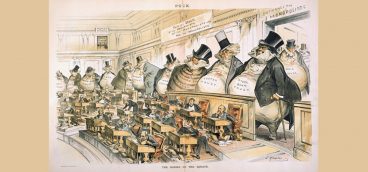

Laissez-faire was intellectually compelling but emotionally unsatisfying. The spectacle of a Rockefeller compounding his billions for years until competition undermined him infuriated people. Even if, ultimately, the economy would be better off allowing competition, rather than the government, to deal with the Standard Oils of the world, many people wanted faster action.

Populism and the Brandeisians

Dissatisfaction with the laissez-faire approach led to a reaction in the exact opposite direction. During the Progressive Era (1896–1916), government intervention in the economy skyrocketed, powered by a populist desire to return to a simpler era when corporations were smaller, more human-scaled.

The intellectual leader of this movement was Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who argued that the increasingly large corporate entities in the United States were both inefficient and “unamerican.” He supported vigorous enforcement of antitrust laws even without claims of monopoly, simply because the companies were large.

As an amusing aside, Brandeis graduated from Harvard Law School at the age of twenty with the highest GPA in the school’s history — until his record was eclipsed by future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. The law school’s grading system was utterly bizarre. The professors took the position that no student could possibly be as smart as they were, and therefore a GPA of 75 out of 100 was considered extraordinarily good performance.

Frankfurter achieved a 77 GPA his first year, an astonishing performance. But when the grades were sent to Frankfurter’s father, the old man wrote to his son saying, “If you can’t do any better than that, my boy, you’d better come home and work in the store.”

Brandeis’s antitrust positions were supported by populist politicians like William Jennings Bryan and Robert LaFollette, but in the end, Brandeisian theories proved to be naïve and simplistic, even downright dangerous.

Even in the early twentieth century, markets were becoming international in nature, and only large corporations could possibly hope to compete on such a large scale. Like it or not, the only options were to accept the ever-growing scale of American industry or to be outcompeted by the large firms growing in England, France and Germany.

Faced with this choice, Brandeisian theories went out of fashion and antitrust enforcement slowed and virtually stopped. As noted earlier in this series, during FDR’s Administration antitrust laws were even waived to allow companies to collude with each other and, FDR hoped, pull the country out of the Great Depression.

At this point in my story, laissez-faire theories had proved to be intellectually compelling but emotionally unsatisfying, while Brandeisian theories had proved to be emotionally gratifying but hopelessly naïve.

It fell to a group of economists and legal scholars associated mainly with the University of Chicago to develop an approach to antitrust enforcement that acknowledged the challenges of a global world while also advocating a more activist approach than the laissez-faire theory would accept. We’ll take a look at the Chicago School next week.

Next in this series: “How to Handle the FAANGs: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part X”