It’s hard to play the alto sax when you’re wearing a mask, so Tony Campbell simply cut a hole in his and played right through the pandemic, appearing at any number of venues from Wallace’s Whiskey Room + Kitchen in East Liberty to a concert on the lawn at a private home in Forest Hills to the Genuine Pub’s Thursday Night Jazz Circuit in Verona. Every other Thursday, some of Pittsburgh’s best jazz musicians join Campbell (in 2010 he was the youngest saxophone player to be inducted into the Pittsburgh Jazz Society’s Hall of Fame) at Helltown Brewing in the Strip for the Alto Madness Jazz Jam Sessions. Vocalist Ruby Vere, a newcomer to the local jazz scene who has performed with Campbell, calls him the “hardest-working musician in Pittsburgh.”

Since 2019 when it began offering live jazz seven nights a week in Shadyside, Con Alma (“with soul”) has been at the forefront of Pittsburgh’s jazz renaissance. Esquire magazine named it one of the “Best Bars in America” in 2021. The place is tiny, seating 50 inside and another dozen on the patio. Pittsburgh jazz guitarist John Shannon is Con Alma’s musical curator. He and his partners — Executive Chef Josh Ross and general manager Aimee Marshal — got creative after the lockdowns, bringing the music outside and offering a limited menu plus cocktails-to-go five nights a week. They also bought a food truck, set it up at 1700 Penn Avenue in the Strip (the current site of Helltown Brewing) and hired musicians to play in the parking lot four nights a week. One of those musicians was Campbell, who is still in residence there every Saturday night for those Alto Madness Jazz Sessions.

If the idea was to keep jazz alive while the country adjusted to a new normal, it worked. Call it a leap of faith in uncertain times, but in July Con Alma opened a second location in the Cultural District. On opening night, Shannon jammed with Campbell and jazz pianist Antonio Croes. The club has gotten positive reviews for the music and the menu, which features a blend of Latin American and Asian-influenced cuisine.

WZUM, the “Pittsburgh Jazz Channel,” started keeping track of jazz activities in and around Pittsburgh in 2017. By the beginning of 2020, the website was posting some 200+ events per month on its Jazz Central calendar (wzum.org). By that time, a few other venues also were supporting local jazz at least one night a week: The Brick Shop & Rooftop at the TRYP Hotel in Lawrenceville, Wallace’s Whiskey Room + Kitchen in East Liberty, Eddie V’s Prime Seafood in the Union Trust Building, Downtown, The Genuine Pub in Verona, and Kingfly Spirits, a distillery and cocktail bar in the Strip.

“With this many places presenting music, it was possible to accommodate a lot more artists,” says Scott Henley, general manager WZUM AM/FM. Then COVID-19 and the lockdowns brought everything to a screeching halt. “See the listings for March and April of 2020,” he says, “but also note the creative approaches in May and June that kept the music playing.” With the lifting of many COVID protocols, Henley noticed an uptick in live events to nearly pre-COVID levels.

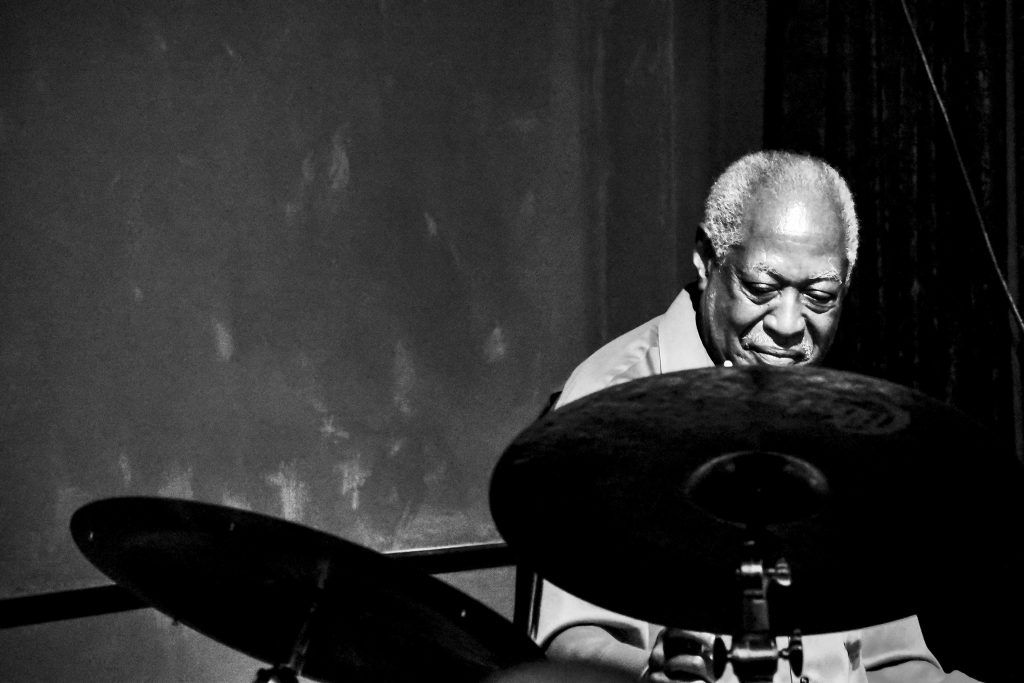

Jazz afficionados, hungry for live music again, showed up in June for “Inside/Out,” the inaugural summer music festival presented by Point Park University’s Pittsburgh Playhouse in collaboration with MCG Jazz, a program at Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild. WZUM was a media sponsor for the event, which showcased some of the area’s best jazz pianists, drummers and guitarists, including three generations of the DeFade family and drummer James Johnson III, an artist-in-residence at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Music.

In August, legendary Pittsburgh jazz drummer Roger Humphries and his band RH Factor boarded the Gateway Clipper with a sold-out crowd for Jazz on the River, his annual fundraiser that provides scholarships to talented young musicians. The event featured a number of local musicians, including renowned jazz and funk bassist Dwayne Dolphin and Campbell, as well as the vocal stylings of Dred “Perky” Scott and Anita Levels.

The jazz scene in Pittsburgh is remarkably diverse. Con Alma has provided a showcase for Latin jazz artists Geña y Peña (Geña on vocals, Carlos Peña on guitar and Tony DePaolis on bass). African American vocalist, Chantal Joseph is a regular at Eddie V’s. Cuban-born Hugo Cruz is an internationally renowned drummer who has appeared at Con Alma, the Frick Museum and the Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival with his band, Caminos, offering a fusion of Cuban, Afro-Cuban and American music. Phat Man Dee, who describes herself as a “cosmic jazz cabaret vocalist” was voted Best Local Jazz Act in 2020 in City Paper’s “Best of Pittsburgh” Reader’s Poll.

“We have a treasure trove of talent in Pittsburgh, a cache of musicians who are playing at super-high levels,” says Chuck Leavens, president and CEO of Pittsburgh Public Media/WZUM. “It’s almost an embarrassment of riches, and I don’t want people to take it for granted.”

Aside from Humphries, who has played with everyone from Dizzy Gillespie and Lionel Hampton to George Benson and Billy Preston, Leavens mentions other artists, like trombonist Reggie Watkins, former musical director for Maynard Ferguson, who plays at Kingfly Spirits about once a month, and internationally known Brazilian jazz singer Kenia, who has lived in Pittsburgh for decades and performs at Alphabet City on the North Side. Kind of Blue (the name pays homage to the studio album by Miles Davis) comprises only teenagers: Marcus Hicks on trumpet, Danny Evans on guitar, Joe Hodges on drums and Eli Alfieri on bass.

Ernest McCarty is a native of Chicago who studied classical piano at 3, was a violin prodigy at 7 and learned to play bass at 13. He moved to Pittsburgh in 1993. Coming of age, his “musical siblings” were Maurice White, later of Earth, Wind & Fire, and Herbie Hancock. “The South Side of Chicago was a humming place,” he says. In the 1980s he toured with Gloria Gaynor as her musical director and played standup bass for Pittsburgh native Erroll Garner, arguably one of the greatest jazz pianists who ever lived and a composer remembered for the jazz standard, “Misty.” During the pandemic, McCarty entertained the neighbors by playing standup bass on his front porch in Lawrenceville, and he still performs at a few venues around town, including Con Alma. Hired as an advisor on “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” which was filmed here, it was his job to ensure authenticity. “If the notes were above middle C,” he says, “then the actor’s hands had to be there too.” In closeups, it’s McCarty’s hands you see when Toledo (Glynn Turmon) plays stride piano — “The bass is hit first,” he explains, “and then you stride in with the chords.”

When we think of jazz, New Orleans, Chicago and New York come to mind, but Pittsburgh’s legacy, which dates back at least 100 years, is just as important. With roots in ragtime and blues coming out of New Orleans, jazz made its way to Pittsburgh in the early 20th century when pianist Fate Marable and his band (Louis Armstrong was a member) traveled north by riverboat. By 1917, singer and pianist Lois Deppe was performing around town in one of the earliest swing bands in the area when he discovered Earl “Fatha” Hines, a seminal figure in the development of what became known as jazz piano. While adept at stride piano, Hines pioneered a “trumpet style” of improvisation, playing single-note solo lines in quick succession much like a horn player. Now, 38 years after his death, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission has approved criteria for a marker recognizing Hines in his hometown of Duquesne.

The list of jazz musicians who cut their teeth in Pittsburgh is impressive and includes composer and bandleader Ahmad Jamal; jazz drummer and bandleader Art Blakey; jazz guitarist Joe Negri; double bassist Ray Brown, who worked with Oscar Peterson and Ella Fitzgerald; Kenny Clarke, who pioneered the bebop style of drumming; David Roy Eldridge, a jazz trumpeter, who played with Gene Krupa and His Orchestra; pop singer and band leader Billy Eckstine; jazz composer, pianist and arranger Billy Strayhorn, who collaborated with Duke Ellington for nearly three decades; George Benson, who began his professional career as a jazz guitarist at 19; Erroll Garner, of course, who died in Los Angeles in 1977 but is interred in Homewood Cemetery; and many more. So, it felt like a slight when filmmaker Ken Burns chose to leave Pittsburgh out of his 2000 documentary, “Jazz,” prompting angry letters to producers from many older musicians in the area.

While jazz has survived and even thrived in Pittsburgh for more than a century, its popularity ebbs and flows. The Crawford Grill has had a number of incarnations, including the original location on Wylie Avenue in the Hill District that was destroyed by fire in 1951. A second location, which opened 10 blocks away in 1942, became the epicenter of jazz in Pittsburgh for the next two decades, booking acts like Chet Baker, Art Blakey, John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Charles Mingus. The club attracted a racially diverse audience, from blue-collar workers to athletes such as Roberto Clemente and celebrities including Frank Sinatra.

FROM LEFT: Jazz guitarist and Con Alma musical curator John Shannon; Dwayne Dolphin; jazz drummer, composer and percussionist George Heid III; Branford Marsalis; and Tony Campbell.

By the 1960s, when hippies were flooding the coffeehouses along Walnut Street in Shadyside by day, it was SRO each evening at clubs like The Encore, where men wore jackets and ties, and cocktails, steaks and live jazz were on the menu. Local businessman Will Shiner opened The Encore in 1959 and began booking jazz legends like Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Art Blakey, Ahmad Jamal, George Benson and Ella Fitzgerald. Trombonist Harold Betters was a regular there for 17 years, garnering national attention when he recorded his first album, “Harold Betters at the Encore,” live in 1962. His shows were so popular that the club became known as the “House that Betters Built.”

In 1961, Shiner opened the private Gaslight Club on Bellefonte Street with a cocktail bar downstairs and fine dining upstairs. Again, live jazz was on the menu. Meanwhile, jazz pianist Walt Harper, who was part of the local jazz scene in the 1940s and 1950s, opened his own club, Walt Harper’s Attic, in Market Square, Downtown, in 1969. For Harper, music transcended differences between people, and the line of fans waiting to hear jazz legends like Stan Getz, Dave Brubeck and Wynton Marsalis often snaked around the block.

Richard “Muzz” Meyers and Bob Feldman came late to the game, opening The Balcony, an upscale restaurant and jazz nightclub in Shadyside in 1980, but the club held its own for 18 years, booking national acts as well as local artists such as Negri, vocalist Etta Cox, Harper and saxophonist Kenny Blake. The last show on New Year’s Eve in 1997 was sold out.

Now jazz is being embraced by a new generation whose grandparents grew up listening to rock’n’roll. “For them, jazz seems fresh and new,” says John Shannon. “You really feel this music when you experience it live.” Done right, he says, jazz is a meeting of high intellect and a deep level of heart. “It takes time to learn the language of jazz, but it’s very rewarding when you do.”

Shannon grew up in Pittsburgh where he studied under jazz giants like Dwayne Dolphin and jazz saxophonist Eric Kloss before attending Berklee College of Music in Boston and moving to New York City. After years of touring, he returned to Pittsburgh, which sparked a new appreciation for the musicians keeping jazz alive here. “Jazz musicians in Pittsburgh are world-class,” he says. “If you’re playing jazz and you’re from Pittsburgh, it means something out in the world.”