It’s Different This Time

“The four most dangerous words in investing are: It’s different this time.” —Sir John Templeton

“The 12 most dangerous words in investing are, ‘The four most dangerous words in investing are: It’s different this time.’ ” —Michael Batnick

Whatever, read my lips: It’s different this time.

From the time the United States was organized as a country right up until 2008—a mere 219 years—majority opinion was straightforward: The American economy was robust enough to fend for itself without massive assistance from a central bank.

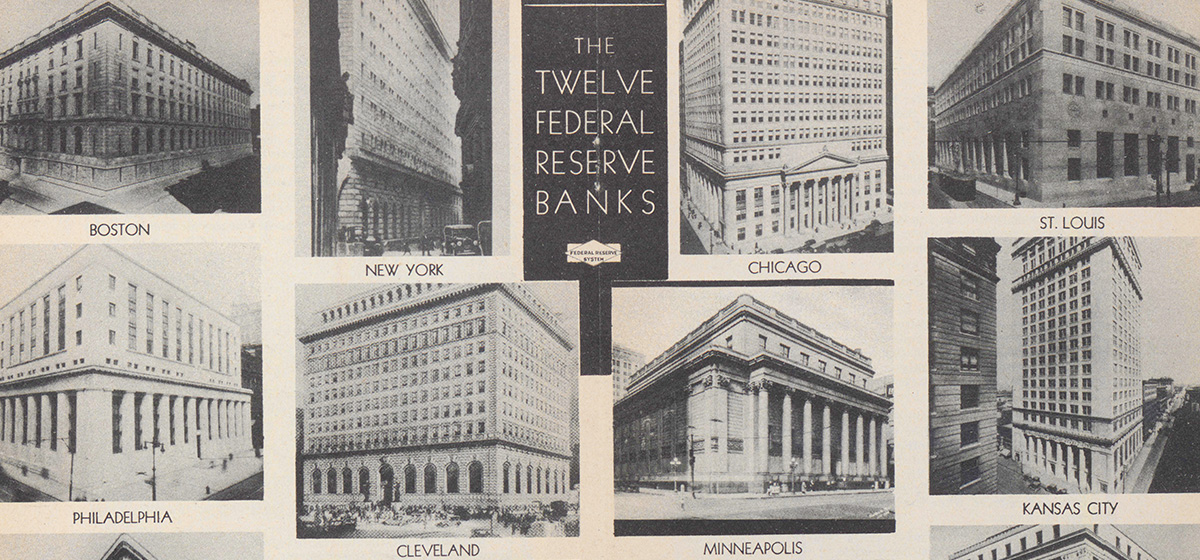

In fact, the first three attempts to establish a central bank in the United States all failed: the Bank of North America (1782, failed 1791); the First United States Bank (1791, failed 1811); and the Second United States Bank (1816, failed 1836). It wasn’t until 1913 that the Federal Reserve System was established.

As an aside, following the Fed’s screw-ups during and preceding the Great Depression, the Fed was subordinated to the Treasury Department and remained there until it was granted its independence in 1951.

True, the idea that the U.S. economy didn’t need a central bank’s help wasn’t always on the mark. When the stock market crashed in 1929 and the country entered a depression, the central bankers of the day should have done more, especially to prop up the banking system.

But that was the only exception, and even though the central bankers dropped the ball, the U.S. economy eventually came roaring back—it powered the Allied victory in World War II and went on to produce the most extraordinary economy in the world from the immediate post-WWII era right up to, well, 2008.

But then everything changed. American central bankers initially did the right thing by propping up the U.S. banking system after Lehman’s collapse. But then they broke the mold, deciding that the U.S. economy was too weak to grow without large and constant and ever-continuing Fed stimulus.

The result was predictable (and not just by Your Humble Blogger): the weakest economic recovery in U.S. history, the lowest inflation in 5,000 years, pathetic productivity gains, a soaring equity market, a vast increase in inequality, populism run riot.

As Mohammed El-Erian has noted, the Fed’s inability to withdraw its stimulus efforts resulted in its “winning the war but losing the peace.” The United States didn’t fall into a depression, but its economy never really regained traction.

Now, bizarrely, the Fed is at it again, as are the rest of the world’s central banks, since Groupthink dominates that hothouse little world.

During the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) the central banks of the G4 countries (the United States, the UK, Japan, and the EU) expanded their balance sheets by 7 percent, an all-time non-war high. When the pandemic hit, those same central banks expanded their balance sheets by 28 percent.

Granted, parts of the economic and financial system needed help when state governments began shutting down the economy, just as parts of the economic and financial system needed help after the collapse of Lehman.

But the Fed has made it clear that it intends to continue its extraordinary intervention not just during the crisis but essentially forever. And since the current intervention dwarfs the post-Lehman intervention, the consequences will be the-same-but-more-so: even weaker economic growth over the next decade, even lower inflation and interest rates, worse-than-pathetic productivity gains, continued massive decoupling of the stock market from the real economy, and a further increase in inequality that the political system won’t be able to handle.

I’ve made this point before, but here it is again: Constant Fed intervention—as opposed to temporary intervention during a crisis—isn’t the result of weak economic growth, but the cause of weak economic growth.

Up until 2008, the United States enjoyed the strongest economy in the developed world, and one of the strongest in the world period. What was the difference after 2008? It wasn’t population growth or decline, since the U.S. population is growing at the same (slow) rate it was before 2008. It wasn’t aging of the population, since median ages barely budged. It wasn’t the collapse of globalization, which was still in full swing. It wasn’t war or international tensions or political crises.

The only thing that changed pre-2008 and post-2008 was central banker interference in the economies of the world’s largest countries. When the banks stabilized in early 2009 and the stock market began to recover, the crisis was behind us and the Fed needed to withdraw from the scene.

But as Lawrence Seigel has pointed out, the Fed’s view of the world is that of “a crisis crisis. Everything that happens is a justification for expensive intervention.”

If that intervention somehow strengthened the real economy, maybe the massive debt the Fed has piled up would be worth it—the U.S. economy might actually grow its way out from under the gigantic albatross.

But, as was true in 2008 and as is even more true today, the Fed’s herculean interventions are designed to benefit Wall Street, not Main Street. Ordinary Americans are struggling with unemployment and small businesses are collapsing at rates not seen even during the Great Depression.

Meanwhile, Wall Street is booming. The stock market is soaring and investment banking and trading revenues at Wall Street firms are up 32 percent over the same period in 2019. Fixed income trading alone is up 56 percent.

The GFC vastly increased the power of central banks—especially the U.S. Fed—and the pandemic has supercharged those powers. Like any individual or institution that has amassed power, the central bankers won’t relinquish it until someone takes it away from them.

By favoring Wall Street and ignoring the consequences of a failing Main Street, the Fed has created, as El-Erian puts it, “the inequality trifecta (of income, wealth, and opportunity.)” Constant intervention in the U.S. economy by the Fed has, in effect, destroyed the American Dream.

Next week, we’ll examine in more detail what the Fed hath wrought.