World’s Fairs asks two questions of themselves: “Who are we?” and “Where are we going?” Sometimes they look backwards as well, perhaps a little wistfully. They also fall into the category of jamboree, a 19th-century slang word of American origin indicating a noisy assembly of people and things for a variety of purposes. Usually they turn out to be a mixture of high and low culture… democratic… educative… and promotional.

Progress, a much bandied-about watchword for all of these fairs, can sound at times like mindless cant, yet that is the ideal they aspire to capture. And these fairs have never been boring, and they so often catch exactly the spirit of their times.

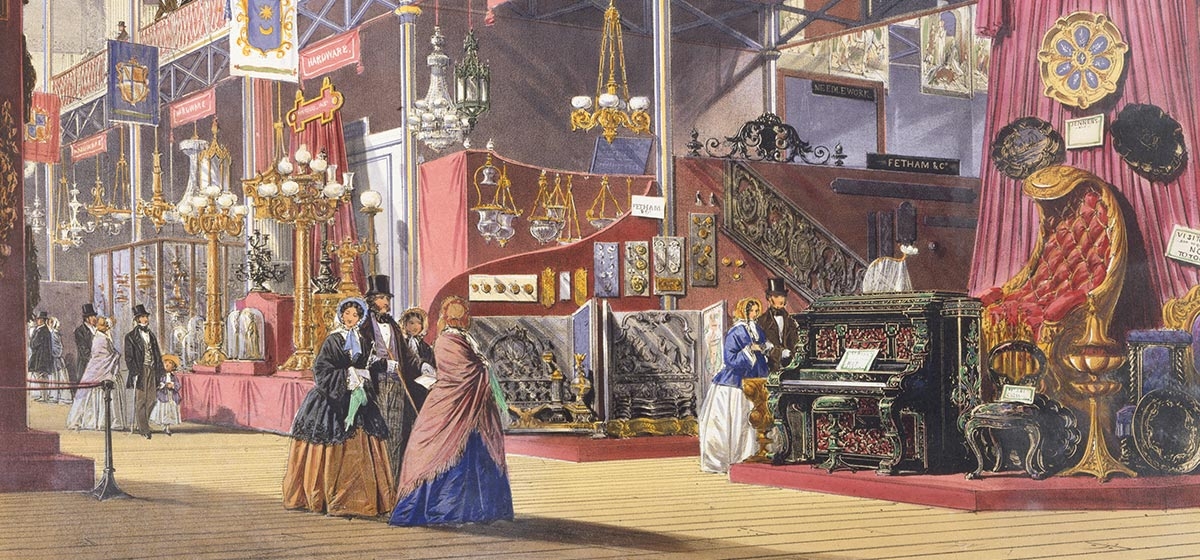

There have been a great many of them, but the idea of the World’s Fair became fixed in the mid 19th century when the phenomenon of cheaper travel made it possible for the local experience to become even global. Smaller, more local expositions (trade fairs really) predate them by over a hundred years, but The Great Exhibition of 1851, also known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition, held in London’s Hyde Park, is generally regarded as the model for all successive examples. At The Carnegie Museum of Art, that momentous happening, chaired by Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, begins a survey of nearly 100 years of such exhibitions in the major cities of the world… but only in so far as it relates to the decorative arts. Thus the jamboree is reduced to a more sober presentation. (In New York in 1939, the last fair to be considered, there were girlie shows to be contemplated as part of the entertainment. Decorative maybe, but not in the Pittsburgh survey).

Most people think of World’s Fairs in the context of the architectural confections which denote each new fair, perhaps with each one trying to outdo its predecessor. Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, constructed of riveted cast iron and the recently discovered plate glass was to give way in time to the reinforced poured concrete of the 1939 paired Trylon and Perisphere buildings, which were essentially modernistic conceptual works. In the years between the architecture of Revivalism, the Beaux Arts Movement and thematic Eclecticism made their entrances and their exits.

At The Carnegie it is important not to lose track of the fact that this is a survey of the decorative arts. The designers of the exhibition thus can only keep the visitor vaguely mindful of the changing architectural ambiance that a hundred years of change implies. Hints, some more obvious than others, suggest the architecture and the interior features of historic gallery space and their accompanying fixtures that would have been found in places as far apart as Chicago, Paris, London, New York, San Francisco, St. Louis and Barcelona, Spain. This is carefully parsed, with studied reference to historic prints, watercolors and photographs. Fabrics (for atmospheric draperies) are matched with documentary textiles, colors are chosen to suggest period, and even a range of display cases has been manufactured and colored-up to evoke the elaborate cabinetry that was part of the complex programming of these shows. So the presentation is more knowing than window dressing, and more indulgent than the neutral installations found in a contemporary museum.

The 1851 Exhibition was technically called The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations and sought to bring together the finest examples of achievement, a term that was to be broadly interpreted. Critics then and now have caviled at much of that achievement, as they have done at all World’s Fairs. The curators of this show are creatures of the 21st century and their concise redaction has the advantage of history at their disposal. They have chosen to select as many works of art as possible that were actually shown in those exhibitions, unearthing quite a few that had been entirely forgotten in the process. They have gone for the best quality they could find, especially in terms of workmanship. The objects are often of superb quality as well as being frequently innovative. Jason Busch, The Carnegie’s chief curator and co-curator of this show, early on made a seminal purchase for the museum with this long planned exhibition in mind, the Tennyson Vase, designed by H.H. Armitage and made by C.F. Hancock & Sons in 1867, which was shown at the 1867 Paris Universal Exhibition. It is superbly well made, and was grudgingly appreciated for that quality by the French silversmith Paul Christofle in the official report of the jury for that exhibition. He also pointed out that English silversmiths were inclined towards the over-grandiose. Silver of this kind has indeed had a rough time of it during the early to mid-20th century, falling from favor and often being scrapped for the value of the precious metal used in their construction. The Tennyson Vase thus carries with it revealing backstories that are typical of such fairs: national pride, national jealousies. Juries, then as now, cannot always be relied on to be even-handed. Christofle’s assertion that the vase’s drawing was faulty might well have received considerable assent in the years when the eclecticism of Victorian silver weighed heavily against it. It was not until the post-war years (1950 and onwards) that Victorian silver was re-evaluated. This exhibition is no less part of that continuing re-evaluation.

Another treasure of this exhibition is a rare loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum of the Yatman Cabinet of 1858 by William Burges, a fine architectural cabinet in the Revived Gothic (Burges’s style is quite unmistakeable) and decorated by Sir E.J. Poynter. Burges’s work slipped into near total oblivion with his death until the 1960s. It is good to have it here for a brief time since another work by this designer, the famous Narcissus Washstand, escaped this museum’s clutches a few years back. Burges was a key follower of A.W. N. Pugin, who did work for the 1851 Great Exhibition, and who is rather sketchily represented in this exhibition with a Bread Plate, ca. 1849, which he designed for the firm of Minton.

It may seem odd that an exhibition titled “Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs 1851–1939” should draw so heavily on revivalist forms. But critics of the time recognized that there was a symbiotic relationship between the innovative and the revivalist. This has never ceased to be the case, even to this day. But there are moments in the chronology of this exhibition when a more palpable tension is revealed. In the excellent catalog there is a chapter written by Stephen Harrison which succinctly outlines the situation: As the 19th century drew to a close, reform-minded theorists began to codify their distaste with the progress of art, architecture and design. Social awareness, a new sense of public rationalism and the input of newer modes of artistic education operated to effect a number of changes. The Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau and other manifestations of this trend (which were by and large nationalist variants of these two tendencies) are theory-based but work to ally craftsmanship and industrial technique with this new mindset. The various World’s Fair settings are classic situations in which these changes (Harrison suggests the term “ebb and flow”) are to be discerned. The 1900 Paris Universal Exposition with its Art Nouveau pavilion set up by Siegfried Bing (an installation suggested here at The Carnegie), with the accompanying displays of Tiffany and Lalique, mark this forward direction. But nothing in that fair more advances modernism than the quite remarkable Pitcher, from 1900, in gilded silver by the Paris firm of Keller Frères. This vessel, beautifully made, represents a reduction of form (still sinuous) that later is paralleled in 1935 by the famous Normandie pitcher by Peter Muller-Munk and anticipates the fully fledged modernism of the Bauhaus in all its manifestations, save one. The Keller Frères pitcher is key to this entire exhibition and sets off the cover of the catalog, but I don’t think it quite draws on any of the scientific influences to which the Bauhaus found itself receptive.

The difficulty in setting up a show of this kind cannot be underestimated. Busch has outlined the logistics of organizing a traveling show (Kansas City, Mo., Pittsburgh, New Orleans and Charlotte, N.C., are its venues), differently constituted in all locations and satisfying the far from exiguous requirements of all the lenders. At the back of the catalog there is an extensive list of nearly 100 World’s Fairs dating from 1851 to 1939! In fairness, this exhibition makes no attempt to deal with them exhaustively (we can forget the 1891 Tasmanian International Exhibition in Launceston, Australia, and quite a few others). The real question is how to deal with the numerous issues brought up by the subject within the loose chronological presentation that is necessary to tell the broad story.

This is done by carving out topics which characterize and inform the narrative. Only one early World’s Fair is closely surveyed, the 1851 Great Exhibition, the model, as one contributor to the catalog, London dealer and scholar Paul Levy, puts it. It remained the model despite successive shows becoming more commercial, and perhaps with the passage of time, more competitively cut-throat, certainly throughout the 19th century. The triumph of modernism (1900–1925) is outlined in an essay by Stephen Harrison, and the show ends on a resoundingly American note with the World’s Fairs in Chicago and New York, 1933 and 1939 respectively.

But that is not enough. There are more things to discuss. These are World’s Fairs, and deal with issues of nationalism and imperialism/colonialism, although not so extensively here. Rather the world is seen as a vast catchment area for stylistic interaction. India and the British Empire play an enormous role (though it should be remembered that India was only administered by the East India Company in 1851). Japan as a stylistic force only begins with the opening of trade with that nation in the third quarter of the 19th century. Islamic design, through the publications of Owen Jones, the design work of Christopher Dresser and (missing in this exhibition) the publications of Emile Prisse d’Avennes is rather well explored. So we encounter an ivory and ebony throne, Islamic-styled glass made in Paris and England, Japanese enamels juxtaposed with French and English imitations. A Japanese woodcut is the source of a series of French transfer-printed faience. Especially alluring are the jewels assembled for this show… works by Cartier, Tiffany, Boucheron and Castellani. And strangest of all are works from countries so seldom encountered in surveys of the decorative arts. Scandinavian textiles may come as a revelation, or the folk arts of Karelia, or Czech tapestry. The colonial empire of Belgium, horrid as it may have been, gave rise to interesting African-inspired furniture and other artifacts, but most notably a strange chair from 1896, derived from the tribal stools of the Kuba, and fashioned by Paul Hankar into what is described as an abstracted face, recalling African masks. All this suggests quite another type of ebb and flow. And finally the exhibition (with its catalog) takes two more in-depth approaches, by way of case studies of the productions of the Viennese firm of glass manufacturers, J. and L. Lobmeyr (a firm that imported much glass to the U.S. throughout the time span of the exhibition) and the infinitely more varied output of the phenomenon known as Tiffany and Company.

It may be that no fully definitive analysis of the long and complex history of the World’s Fairs could ever be presented, but this show for the first time puts the major role of the decorative arts in its proper perspective. It is unlikely that another World’s Fair could ever take place again, and if it did, it would be radically different from any of its predecessors.

In a way this exhibition rather underpins the policy of the decorative arts department at The Carnegie under its three most recent curators, Phillip Johnson (later director of the museum), Sarah Nichols (sometime chief curator) and Jason Busch (currently chief curator). Many of the acquisitions of their respective tenures appear in this exhibition. The exhibition itself is curated jointly by Busch and Catherine Futter, curator of decorative arts at the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Mo.