In China, the Unraveling Begins

“It is time for the United States to stand up to China in Hong Kong.” —Elizabeth Warren

Just for fun, let’s go back to 1842, which is when China “lost” Hong Kong. Most Westerners seem to think that the Brits had a 99-year lease on Hong Kong, that that lease terminated in 1997, and that the island accordingly reverted back to China. The truth is both more complicated and almost exactly the opposite.

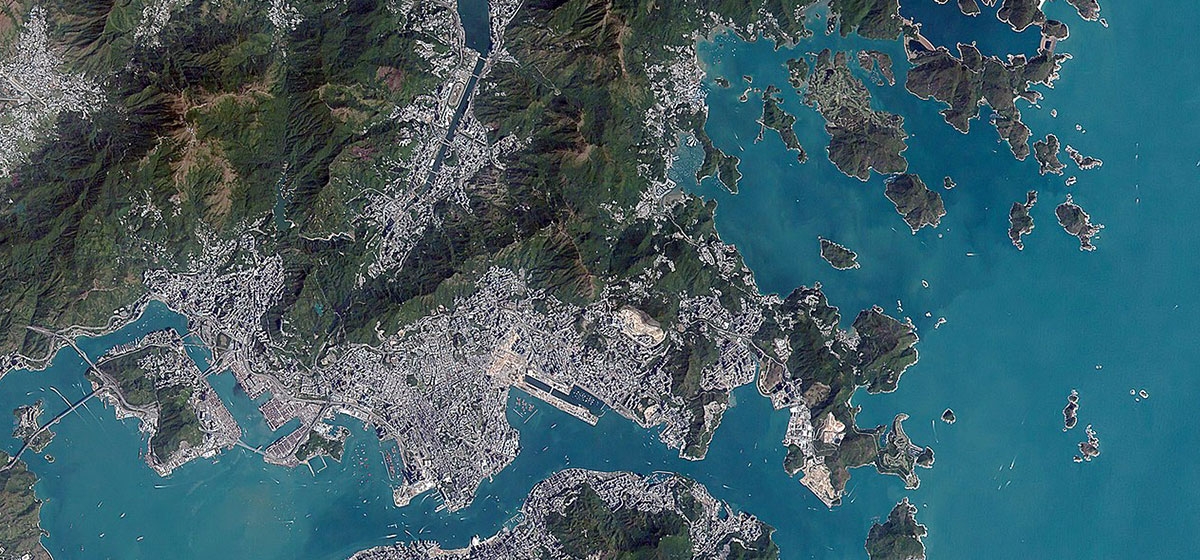

Following Britain’s victory over the Qing Dynasty in the First Opium War, China ceded Hong Kong to Britain in perpetuity (not for 99 years). At that time Hong Kong was a disease-ridden, under-populated island, but over the next few years, chaotic conditions on the mainland led to growth in Hong Kong’s population, commerce and general importance.

Then, following its victory in the Second Opium War in 1860, Britain also acquired the Kowloon Peninsula in perpetuity via the Convention of Peking.

During the subsequent three decades Hong Kong continued to prosper, becoming an important entrepôt for Britain in the Far East. By this time, however, Britain had begun to realize that it was virtually impossible to defend Hong Kong against Chinese and European aggression without also controlling additional territory. Thus, in 1898, acting under the most-favored-nations status it had acquired from Peking, Britain demanded additional territory.

Which is where the 99-year lease comes in. Under the terms of the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory, Britain leased the so-called New Territories from China for 99 years. At this point, and right up to the present day, Greater Hong Kong has consisted of Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, and the New Territories.

Why a 99-year lease? In part because, under English common law, 99 years was the longest lease of real property that was permitted. This was a version of the Rule Against Perpetuities; indeed, some American states continue to limit real property leases to 99 years by statute.

Also, in part, 99 years seemed like a very long time to people in the late nineteenth century, when time moved more slowly than it does today. Claude MacDonald, who represented the British in the negotiations, decided on a 99-year lease because he thought it was “as good as forever.” And, in point of fact, no one in Britain believed they would ever be forced to return the New Territories.

Now that we know what actually happened back in the day, let’s fast forward to the late twentieth century.

In the early 1980s, with the end of the 99-year lease coming into view, China began demanding the “return” of Hong Kong. And, bizarrely, Britain agreed.

Given that the Brits owned, in perpetuity, two of the three regions of Hong Kong, while China was entitled only to get the third region back, it certainly seemed as though Britain had the better case. Yet, without a whimper, the Brits caved. How could such a thing have happened?

We might speculate that it happened as the result of:

An act of cowardice? The Brits were terrified by the growing power of China and wanted no part of a military confrontation with the People’s Liberation Army. It never seemed to occur to the Brits that Taiwan had been independent of China since 1949 and, China’s rage notwithstanding, it remains independent to this day. Instead, Britain backed down and handed seven million people over to Communist tyranny. Hell, if China had demanded London I bet the Brits would have given it to them.

An act of greed? The Brits, who had governed Hong Kong for 155 years, threw seven million people under the bus because, like everyone else in the West, they were positively salivating over access to the huge Chinese markets. What is the fate of seven million people who had loyally served Britain for 155 years compared to that?

An act of—perhaps unconscious—racism? To the Brits, and probably to almost everyone in the West, it appeared that, since the residents of Hong Kong were Chinese, and so were the residents on the mainland, the two should be part of the same country. A Chinese-is-a-Chinese-is-a-Chinese.

To examine how preposterously racist this attitude was, let’s examine an analogous Western example. In 1936, a mere six years before China “lost” Hong Kong, Spain “lost” Mexico. As a reminder, China lost Hong Kong as a result of its defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars. By the same token, Spain lost Mexico as the result of a series of military defeats.

As you will recall, Mexico had declared its independence in 1821, but Spain never recognized that declaration and tried for years to “reconquer” Mexico. Those efforts ultimately failed with the Spanish defeat at the Battle of Pueblo Viejo, and in 1836 Spain recognized Mexico’s independence via the Treaty of Santa María–Calatrava.

Suppose that, in the late twentieth century, Spain had demanded the “return” of Mexico? Spain would have been laughed out of court. Why wasn’t China laughed out of court? Because, as noted above, in Western eyes, it appeared that people in Hong Kong and people in China were all alike and should therefore be under the same sovereign.

In fact, residents of Hong Kong are far more different culturally from residents of mainland China than residents of Mexico are from residents of Spain. Residents of Spain and Mexico speak the same language; the two countries have nearly identical GDPs; both are cosmopolitan nations that have attracted many foreign-born residents; most important, both are representative democracies characterized by broad civil rights, the rule of law, separation of powers, and free speech.

Residents of Hong Kong and mainland China meanwhile, speak different languages (Cantonese and Mandarin, respectively, the two languages being mutually unintelligible); Hong Kong residents earn incomes four times as large as mainland residents; Hong Kong is a cosmopolitan city that has attracted many foreign residents, while China has fewer foreign residents than any country in the world (yes, including North Korea). Most important, 15 decades of British rule has meant that people in Hong Kong expect broad civil rights, rule of law, separation of powers and free speech, while residents on the mainland expect tyranny.

Now that we know the actual facts, let’s take a look next week at what should have happened to Hong Kong.