Ignoring What We Knew

“One who excels at sending forth the unorthodox [army] is as inexhaustible as heaven.” –Sun Tzu, “The Art of War,” Chapter 5

In the case of Vietnam, we don’t need to speculate about how Gen. Sun Tzu would have conducted the war, for the simple reason that the U.S. military already knew how to conduct it. Unfortunately, that knowledge was lost to the closed minds of William Westmoreland and our other senior military and civilian leaders.

As noted earlier in this series, America had fought almost 200 small or proxy wars, including many guerilla insurgencies. And almost all those wars were brought to a successful conclusion.

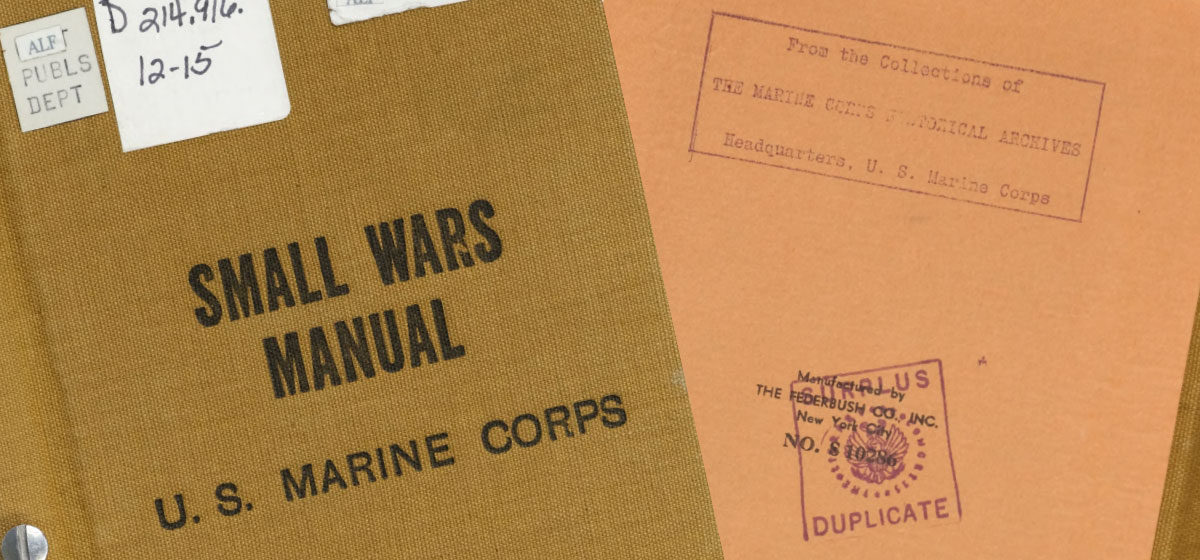

In 1940, the consolidated experiences of these hostilities was collected by the Marine Corps into the “Small Wars Manual,” a work that could almost have leapt directly from the pen of Gen. Sun Tzu.

Consider these excerpts from the manual:

“In dealing with the local population [for example, in Vietnam] courtesy, friendliness, justice, and firmness should be exhibited.”

“A… commander who gains his objective in a small war without firing a shot has attained far greater success than one who resorted to the use of arms.”

“All officers upon assignment to [combat guerilla insurgencies] should study and acquire a working knowledge of the local language.”

“[The key to victory over a guerilla insurgency in any country is] serious study of the people.”

“A hungry man will not be inclined to listen to reason.”

“In small wars, caution must be exercised, and instead of striving to generate the maximum power with forces available, the goal is to gain decisive results with the least application of force and the consequent minimum loss of life.”

“Friendships should be made with the inhabitants in an honest and faithful endeavor to assist them to resume their peaceful occupations.”

“When native troops are available, they may be included in the patrol. They will … do much to establish friendly relations between the peaceful inhabitants and the intervening force.”

“Night marches are practicable and desirable… Training for small wars operations places particular emphasis upon the following subjects: *** Night operations, both offensive and defensive.”

It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that America’s war plan in Vietnam was exactly the opposite of the war plan recommended in the “Small Wars Manual.”

The centerpiece of American strategy in Vietnam was the so-called “search-and-destroy” patrol. The idea was that army and marine patrols would scour the countryside, engage the enemy, and defeat them with vastly superior firepower.

But there was a big problem with this strategy: the enemy wasn’t interested in being engaged. Hanoi and the Viet Cong had no illusions that they could defeat the Americans in head-to-head confrontations, and so such confrontations were avoided.

During the day, while the Americans were wasting their time and their lives on search-and-destroy patrols, the Viet Cong remained hidden in the jungle. At night, while the Americans remained inside their heavily guarded bases, the Viet Cong controlled the countryside. By the time I entered the army, grunts ridiculed the search-and-destroy patrols by referring to them as search-for-phantoms-and-destroy-yourself patrols.

But not everyone in the U.S. military had forgotten how to fight guerilla wars. Consider, for example, CAP and Operation Phoenix.

CAP

While Westmoreland et al. were trying and failing to win the war via the application of massive superior firepower, a few lower-level commanders were following Sun Tzu (via the “Small Wars Manual”).

The most prominent and successful of these efforts was the Combined Action Platoon—CAP—an idea taken directly from the “Small Wars Manual” and which turned the main American war plan on its head.

Instead of sending out patrols during the day and returning to base at night, CAP operations would occur during the nighttime, denying the Viet Cong any chance of controlling the countryside.

Instead of remaining inside American bases, isolated from the Vietnamese people (not counting hooch maids and prostitutes), CAP units would live in the villages among the people.

Instead of patrolling using exclusively American military units, CAP units would patrol jointly—and live jointly—with South Vietnamese local militia soldiers who knew, intimately, the villages, the people, and the jungle.

In total, roughly three million Americans would serve in Vietnam, most of them draftees, but the CAP program relied on tiny groups of volunteers, all marines.

Vietnamese villages were for the most part laid out differently from what Americans would think of as a “village.” In the United States, a village is a group of people who live close to each other in one cluster. But in Vietnam, a village was usually a group of small clusters of people spread out, sometimes for miles, along a valley or stream.

The village might have, in total, 3,000 to 7,000 residents (after that it would likely be a town). How many soldiers would it take to roust out Viet Cong guerillas and keep them out, allowing the people of the village to “resume their peaceful occupations”?

If you are Army General Westmoreland, your answer would be something like, “A battalion would probably do it, assuming air support [i.e., about 1,000 soldiers].”

If you are a Marine CAP commander in the field your answer would be “A marine rifle squad would do it [i.e., 12–15 marines].”

True, the rifle squad would be paired with a South Vietnamese Popular Forces militia platoon (25–30 militiamen), but the militia was made up of part-time, poorly trained, poorly paid and poorly equipped young men.

Poorly trained or not, when paired with highly combat-ready marines, the combination of marines and militiamen represented a formidable fighting unit, easily a match for anything the Viet Cong could mount against them.

How did these tiny CAP units fare? We’ll find out next week by looking into the classic description of CAP marines in action, contained in a book called “The Village.”