How We “Lost” Vietnam

Happy New Year!

After all the stupidity, all the lies, all the inflated body counts, all the unnecessary deaths, in spite of it all, by 1968 an American victory in Vietnam was within easy grasp. Even Westmoreland could have managed it.

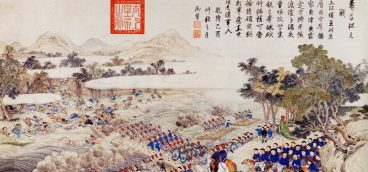

Why? Because the enemy had made a spectacular and unforced error: the Tet Offensive.

Tet—the Vietnamese New Year—was the biggest holiday of the year in both North and South Vietnam. To allow people to celebrate, Hanoi had announced in October of 1967 that it would observe a seven-day truce, beginning on January 27, 1968 and ending on February 3.

But Hanoi violated its own truce, and on the morning of January 30 a massive, long-planned offensive was launched all across South Vietnam, taking the Americans and South Vietnamese completely by surprise. But the Tet Offensive was the child not of confidence and strength, but of desperation.

Hồ Chí Minh had begun fighting in 1941 against the Japanese and he had not been at peace since. Twenty-seven years later Hồ was seventy-eight years old and in ill health; he would live only one more year.

In Hồ’s absence, the North Vietnamese Communist Party had fractured into numerous factions, the most important of which were headed, on the one hand, by Võ Nguyên Giáp, Hanoi’s famous general, and on the other by Party First Secretary Lê Duẩn.

Giáp’s wing of the party was “moderate.” He knew all too well how much the war had drained North Vietnam and, especially, its economy. The country couldn’t take much more and the best way out of the morass was to open negotiations with the Americans. Giáp was backed in this position by the Soviets.

Lê Duẩn headed the militant wing. They were well aware of the weak state of the North Vietnamese economy, but they were rigid Communists who viewed moderate opinion as akin to treason. In these positions Lê Duẩn was backed by the Chinese.

Lê Duẩn and his faction concluded that the best way to salvage the war effort would be to make one final, massive assault on the South, using every Viet Cong asset, backed where necessary by the North Vietnamese regular army (the NVA). Most large towns and cities would be captured during the offensive and, once the people of the South saw how powerful the Communists were, they would rise up as one, join the offensive, and drive the American aggressors out of the country.

This was purest fantasy, and Giáp saw it for what it was. But when he began to argue against the offensive his entire military staff was purged and imprisoned during the so-called Revisionist Anti-Party Affair. Giáp himself was too powerful to take down, but he recognized the danger he was in and quickly took himself off to Hungary for “medical treatment.”

The Tet Offensive was launched without Giáp and, at first, it achieved some modest gains. The U.S. Embassy compound in Saigon was breached and the ancient capital city of Huế was captured. At Huế, the Viet Cong promptly massacred almost 3,000 civilians.

Although control of the embassy was regained in a few hours, U.S. Marines and South Vietnamese forces fought a brutal, month-long, house-to-house battle before the Viet Cong were driven out of Huế.

But out of literally hundreds of targets across South Vietnam, none was taken and held by the Viet Cong, even when backed by NVA forces. No South Vietnamese units defected to the North, and not a single village, town or city joined the Tet Offensive.

Of the roughly 100,000 Viet Cong fighters involved in the Tet Offensive, 50,000 were killed, and thereafter the Viet Cong were never a factor in the war.

Hanoi was stunned by the failure of Tet, and Lê Duẩn and his militant wing of the Party lost face and influence. This was undoubtedly the darkest period for North Vietnam since its great victory over the French back in 1954: Hanoi’s main combat force in the South, the Viet Cong, had been destroyed; the North Vietnamese army was no match for the Americans; the economy of the North was in tatters.

Last, but not least, Hanoi’s main patron, the USSR, had had enough of the war and was putting immense pressure on Hanoi to launch negotiations with the United States. If the Soviets withheld aid and equipment, Hanoi would be dead, just as Saigon would be dead without U.S. aid and equipment.

At this exigent moment, with North Vietnam reeling, the Americans simply walked away from the war. Under public pressure to end the fighting—the U.S. media had portrayed Tet as a great Communist victory—and to stop the killing of American boys, President Nixon announced that American soldiers would no longer engage in combat. Henceforth all ground operations would be conducted by the South Vietnamese army.

Gen. Giáp could hardly believe his ears. Surely this was some capitalistic plot! But, impossible as it seemed, it was true. Sun Tzu’s remark, which launched my discussion of Vietnam, is one of those observations that is true in all countries and at all times: “No country ever profited from protracted warfare.”

The American media and the American public had simply had it with the United States’ handling of the war and it didn’t matter who’d prevailed in the Tet Offensive, whether or not Hanoi was on the ropes, or whether the moon was made of green cheese.

The United States was so desperate to end the war that it sold out South Vietnam and, far worse, sold out the mainly recent high school graduates who’d fought so bravely, and died so uselessly, for so long. There wasn’t a working-class kid in America in the early 1970s who hadn’t lost friends in that awful war.

What would Gen. Sun Tzu have made of this dog’s breakfast? We’ll find out next week.