How to Handle the FAANGs

“Consumers won’t thank antitrust enforcers for repeating the mistakes of the past.” —Jessica Melugin, Competitive Enterprise Institute

Previously in this series: “Laissez-Faire vs. the Progressives: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part IX”

The so-called Chicago School approach to antitrust enforcement has many fathers and they rarely agree on much. In addition, the school has evolved over time, especially through the work of people like Robert Bork and Richard Posner.

That said, the Chicago School has been dismissive of almost everything about the Brandeisian approach. Its proponents argue that many of the corporate strategies the Brandeisians believed to be anticompetitive were in fact completely reasonable: They improved corporate operating efficiency and allowed companies to compete against other large domestic and foreign corporations.

The school agrees with the laissez-faire theorists that in many cases activities that are concededly anticompetitive are nonetheless best dealt with by market competition, not government bureaucrats. On the other hand, unlike the laissez-faire approach, the Chicago School does find certain activities to warrant government action, rather than wait for the market to eliminate the problem.

At the core of the Chicago School approach is the “consumer welfare standard.” While difficult to define, the standard at least focuses thought on the needs of the consuming public, rather than on bigness or arcane issues like “predatory pricing.” This approach focuses not on protecting individual competitors but on preserving competition. It insists on using economics to analyze the efficiency of markets and market sectors.

The Chicago School approach has been so successful that it has dominated the world of antitrust enforcement in the United States since the 1970s. It is not without its problems, of course, as I’ve detailed in earlier posts in this series.

One particular recurring problem is the definition of the relevant market. If a company is being accused of monopolizing a particular market sector, it’s crucial to understand what that sector is. Unfortunately, governments are extremely bad at understanding the true nature of market sectors.

Very often, when the FTC or Justice Department loses an antitrust case it’s because the courts didn’t agree with the government’s definition of the market sector that was supposedly being monopolized. Is Amazon dominating the retail market sector? Hardly, since it has only about 5 percent of that market. Is it dominating the online retail market sector? Maybe, since it has almost 15 percent of that market, much more than anyone else. But which market sector is more relevant to deciding if Amazon is a monopolist?

Looking ahead

The Chicago School has had a good run, dominating antitrust thinking for half a century. But the astonishing rise of the great technology companies has badly stressed the Chicago School approach.

The so-called FAANGs — Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google (and we could add Microsoft, which is second only to Apple in terms of revenue) — seem to many people to be creatures wholly outside traditional antitrust thinking. Or, at the very least, to beg the question of what consumer welfare really means in the context of the huge platform companies.

A “platform company,” by the way, has different meanings in different contexts. Here I mean companies that are digital communities and marketplaces that enable transactions and interactions on a massive scale. This is a wholly new business model and it is one where first-mover advantage is crucial.

Today, astonishingly, seven of the 10 largest firms in the United States (by revenue) are platform companies or at least platform hybrids. Think Amazon with its marketplace, Apple with its AppStore, or companies like Facebook and Google that were founded as standalone platform companies, although they (especially Google) have expanded into other businesses.

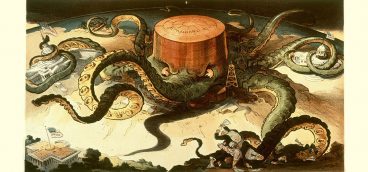

Can a core antitrust law passed in 1890 possibly be used effectively against these new behemoths? Does “consumer welfare” refer only to pricing? Many platform businesses, after all, are free to the user, and others, like Amazon, have driven consumer prices down dramatically.

The many challenges of trying to apply the Chicago School’s consumer welfare standard to the tech giants has led to the rise of a possible fourth antitrust theory, the so-called “neo-Brandeisians.”

Neo-Brandeisian thought isn’t really a new theory, since it doesn’t pretend to add much to the original Brandeisians. Essentially, neo-Brandeisians are opposed to big companies just because they are big. Also — much like Brandeis himself, albeit a century later — the neo-Brandeisians want to use antitrust law to achieve other policy goals they support, including strengthening labor unions, reducing inequality, enhancing privacy protections and so on.

Given the lack of new content in neo-Brandeisian theory, many Chicago School adherents dismiss it as “hipster antitrust.” That’s probably not far from the truth, but merely because neo-Brandeisian ideas don’t much resonate doesn’t mean that the Chicago School is up to the task of dealing with the tech giants.

Just as a simple example of how complex the problems are, consider that it is true that the tech giants have produced — and invented — incredible products that are much in demand and have simplified people’s lives and reduced prices across the board. On the other hand, studies show that, viewed as an overall economy, competition and productivity have declined in the United States, boding poorly for America’s future.

Would we rather pay a bit more for our books, movies, phones and Internet searches and live in a more robust and faster-growing economy? Or is that too high a price to pay? Or, is it even true that competition and productivity are in decline? Maybe the old-fashioned tools we use to measure such things simply don’t capture the true vigor of the modern, high-tech U.S. economy.

Before we consider whether there are better ways to approach antitrust policy, especially in an economy dominated by the tech giants, let’s take a quick look at some of the more pressing complaints about the FAANGs and their brethren. We’ll delve into that hornets’ nest next week.

Next in this series: “The Coming Missteps on Big Tech: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part XI”