History’s Lessons and Historic Mistakes

Angela Merkel’s Reputation Is Trashed – But Is America at Fault?

Merkel’s reign at the top of Germany’s political apparatus was remarkable, and she stepped down as something of a secular saint with a 77% approval rating. But it’s amazing what six months can do.

Previously in this series: A Coat of Varnish Part III, Not Everyone Agrees With Us

Today, post-Ukraine, Merkel’s reputation is in tatters, as all her signature policies have proven to be not just wrong, but disastrously wrong. As Jeremy Cliffe, a writer for the New Statesman, put it, “[Merkel’s] foreign policy sacred cows are now a steaming pot of beef stew.”

Merkel advocated (a) appeasing Vladimir Putin, (b) allowing her country to become utterly dependent on Russian energy, and (c) keeping German defense spending well below the minimum NATO threshold of 2% of GDP. All those policies have now been discredited and discarded, almost as though Merkel never existed.

The nadir for Merkel was probably when Ukrainian President Zelensky invited her, in the middle of the war, to visit Kyiv to get a close-up and personal view of her failed policies. (Merkel declined.) As the Financial Times put it, Merkel’s policies toward Russia were “part willfully naïve, part deeply corrupt.”

Of course, Merkel was hardly alone in allowing her country to become dependent on a despotic kleptocracy. In their zeal to reduce carbon emissions Europe reduced oil production to 3.6 million barrels/year while consuming 15 million barrels/year. Note, however, that this didn’t reduce carbon emissions by one whit – it simply transferred energy production from Europe to Russia and elsewhere. Europe’s virtue signaling didn’t make the world a cleaner place, but it certainly put its national security in jeopardy.

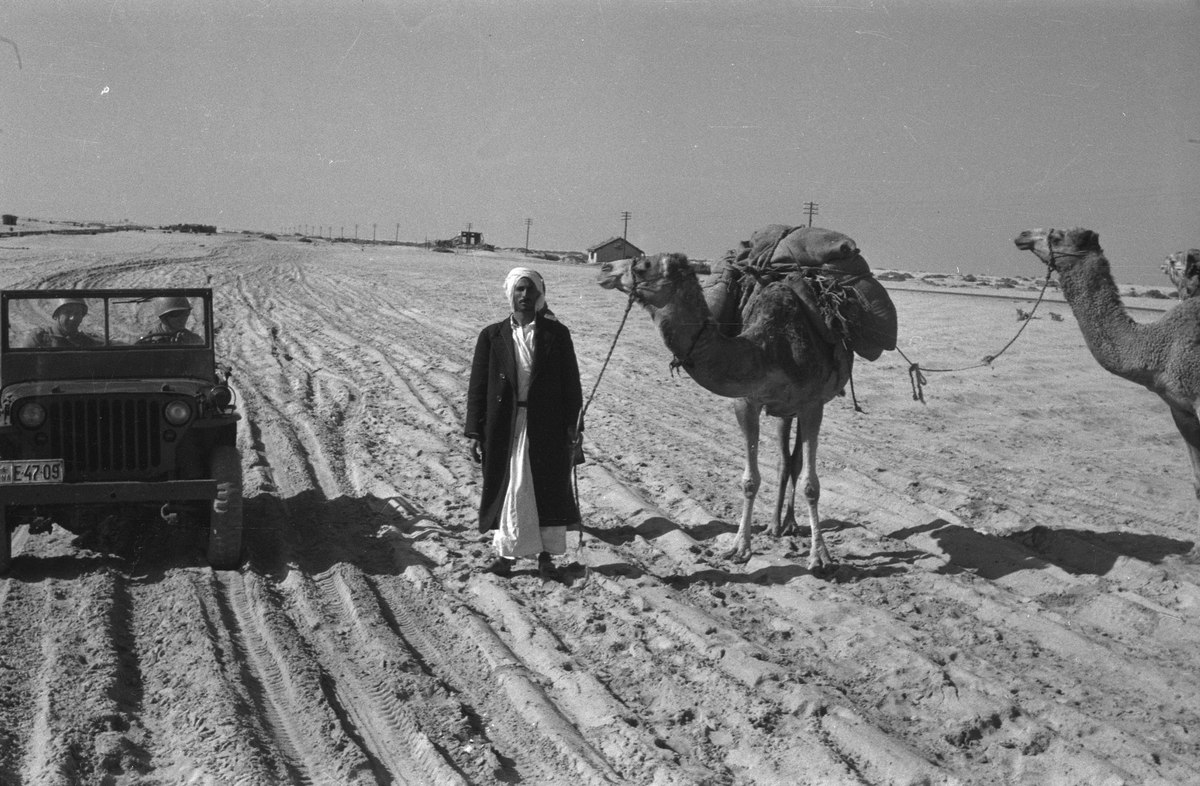

But before we wallow in too much Schadenfreude – Merkel was repeatedly warned by America that her policies were short-sighted and dangerous – let’s examine America’s role in pushing Germany into Russia’s arms. To do that we have to go back to the early 1950s, when America encouraged Europe to become reliant on cheap oil from the Middle East.

That oil had to pass through the Suez Canal – two-thirds of Europe’s oil went through the canal – but in 1956 Egyptian President Nassar nationalized the canal, halting Europe’s oil supplies. Britain and France, furious at this threat to Europe’s economy, invaded Egypt, along with Israel.

Any one of those armies was capable of defeating Egypt’s feeble and poorly led forces, much less all three. But just when it seemed Nassar would be crushed, America intervened.

The United States liked to think of itself as an anti-colonial power, unlike the Europeans, and it wasn’t about to stand by while European armies beat up on Egypt. Moreover, the U.S. was busily competing with the Soviet Union for influence in the Middle East, and that project wasn’t going well. (Syria, in particular, had cozied up to the USSR, a relationship that continues to this day with the Soviet successor, Russia.) If the U.S. allowed Britain and France to defeat Egypt, America’s hopes in the Middle East would surely be ended.

When America’s UN resolution calling on the combatants to withdraw was vetoed by Britain and France, it was time to take the gloves off. President Eisenhower warned Britain that if it didn’t halt the invasion the U.S. would destroy Britain’s economy.

America owned a vast store of UK-issued sterling bonds and if those bonds had been dumped on the market the consequences for an already-weakened UK would be dire.

Harold Macmillan, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, told Prime Minister Anthony Eden that if the U.S. made good on its threat, the value of the pound sterling would collapse, the country’s foreign exchange reserves would quickly be exhausted, and within weeks the UK would be unable to afford the cost of food and energy supplies needed to sustain the British population. The war against Egypt quickly ended, making Nassar a hero.

Angela Merkel was only a baby when those events occurred, but she was an astute student of history. She quite sensibly concluded from the Suez crisis that (a) Germany should never again find herself dependent on Middle East oil and (b) Europe could never know when it might be stabbed in the back by America.

Merkel’s policies proved to be ruinous, but she didn’t invent them out of thin air.

Ukraine Is Different from South Korea How?

“The offensive during the Korean War was an emergency program, but it created enduring strategic advantages that largely determined the Cold War’s outcome.” — Michael Beckly (Tufts) and Hal Brands (Johns Hopkins)

In 1950, when North Korea invaded South Korea, the U.S. was not a party to any treaty requiring it to come to the latter’s aid – exactly like Ukraine, a non-NATO member. South Korea was not included in the Asian Defense Perimeter outlined by Secretary of State Dean Atchison. The U.S. had been steadily withdrawing troops from South Korea as part of the broad military scale-back following the end of World War II, and Atchison strongly implied that the U.S. had no strong strategic interest South Korea.

In addition, by the time of the invasion of the South by the North, Japan had not yet been reintegrated into the free world and the USSR already had the atomic bomb, ending America’s nuclear monopoly.

Finally, Korea was 7,000 miles away on the other side of the world, raising massive logistical issues, while Ukraine sits in the heart of Europe.

Yet the U.S. promptly came to the aid of South Korea, despite the lack of a treaty, despite the fear of a nuclear confrontation, despite distance, and – incidentally – despite the fear that China might become involved in the war, which it eventually did. In fact, Korea launched a global campaign to strengthen the anticommunist world, resulting in, among other things, NATO.

There are, of course, many specific differences between Korea and Ukraine. But at the end of the day, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that an earlier generation of Americans was tougher, wiser, and braver than we are. Russia took note and acted accordingly, and China is watching closely.

Next up: A Coat of Varnish, Part 5