George Gershwin will be forever associated with New York City. This most American of composers derived his inspiration from Manhattan’s energy, skyscrapers, jazz, nightlife, and evolving Broadway-musical art form.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”65″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Nevertheless, in the 1920s and ’30s Gershwin and his music traversed the nation, often ending up in Pittsburgh.

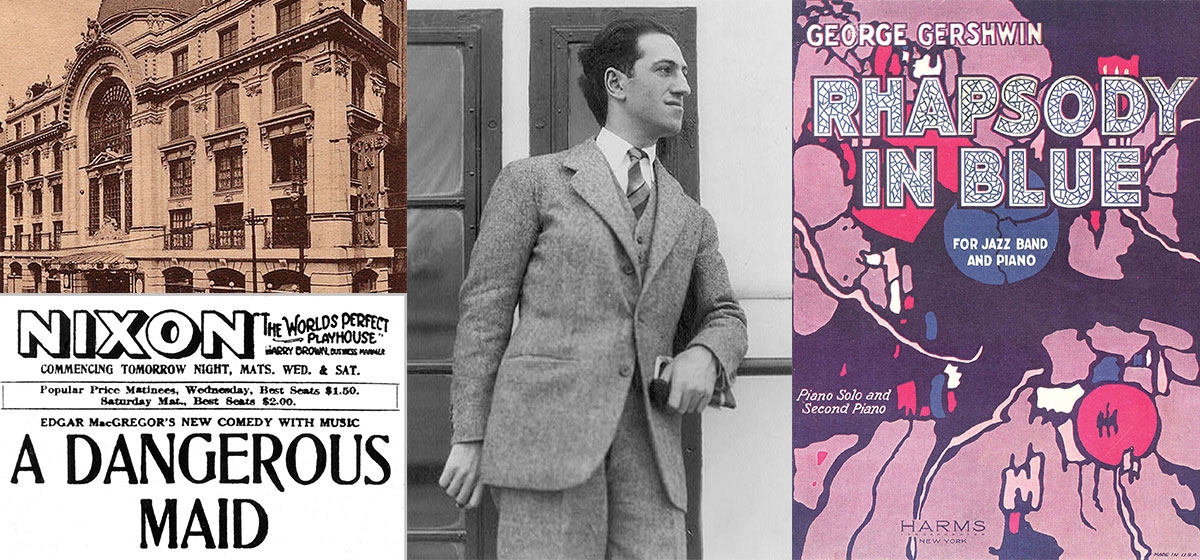

New York musicals and plays of the time normally opened out of town as “tryouts,” allowing fine-tuning before their arrival on the Great White Way. After a successful Broadway run, a musical might tour cities across America. Gershwin’s earliest songs were heard in Pittsburgh, usually at the Nixon Theatre, an opulent domed playhouse located until 1950 on Sixth Avenue.

One of the initial opportunities for Pittsburgh audiences to enjoy a Gershwin tune in its stage context was during performances of “Hitchy-Koo of 1918” at the Nixon. For “Ladies First,” Gershwin visited Pittsburgh (where it was called “Look Who’s Here”) during a 1918 multicity tour with vaudeville singer Nora Bayes. The musical incorporated “The Real American Folk Song Is a Rag,” which is the first publicly performed song written by the team of George and Ira Gershwin (under the name Arthur Francis). Attending one of the show’s performances was Oscar Levant—then 12 years old—who would turn up at Gershwin’s New York apartment in the mid-1920s and soon become his musical alter ego.

In his autobiographical book, “A Smattering of Ignorance” (1940), Levant recalled the 1918 show: “After one chorus of the first song my attention left Bayes and remained fixed on the playing of the pianist. I had never heard such fresh, brisk, unstudied, completely free and inventive playing—all within a consistent frame that set off her singing perfectly. Later, when I reminded George of the show and his part in it, he remarked that Bayes was constantly complaining that his playing distracted her from what she was trying to do, and that she frequently threatened to get somebody else.”

Pittsburgh continued as a venue for Gershwin firsts. “A Dangerous Maid,” starring Vivienne Segal, opened at the Nixon on April 11, 1921 and soon closed there. One of the most obscure Gershwin shows, it never made it to Broadway. An important landmark in the composer’s career, Gershwin’s “Pittsburgh musical” was the first one he wrote with his brother Ira (again as Arthur Francis).

In the early 1920s, George Gershwin—now the famous composer of “Swanee”—was involved in a successful series of annual revues, “George White’s Scandals,” one of which arrived in Pittsburgh on Jan. 15, 1923. It featured the Paul Whiteman Orchestra and introduced one of Gershwin’s most characteristic rhythm songs, “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise.” By the following year, Whiteman had the idea of a concert demonstrating that jazz and American popular music could be taken seriously as art. He booked his “Experiment in Modern Music” at New York’s prestigious Aeolian Hall for February 12, 1924. Victor Herbert—who had been conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony from 1889 to 1899—contributed “An American Suite” (ultimately “A Suite of Serenades”), and Gershwin was pianist for his own “Rhapsody in Blue.” During the subsequent road tour, Gershwin played at Pittsburgh’s Syria Mosque on Saturday afternoon and evening, May 17, 1924.

In 1933, Gershwin returned to Pittsburgh as a soloist in a special concert by the Pittsburgh Symphony. A lengthy article in the Nov. 20 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette said the sold-out event at the Syria Mosque represented “the largest crowd ever to attend a symphony concert” there: “Gershwin himself made Pennsylvania history on the steps of the Mosque yesterday afternoon, selling the first ticket—first for the concert and first ever legally sold for a Sunday concert in the state.” The article also reported Gershwin’s comments to the newsreel cameras: “I consider it a great honor to be able to sell the first ticket ever sold in Pittsburgh for a Sunday concert. Although I like blue music, I can’t say I’m very fond of Blue Laws.”

By this time, Pittsburgh-born Oscar Levant was an essential part of Gershwin’s circle. In “A Smattering of Ignorance,” Levant discussed his role in the 1933 visit, which occasioned one of the notorious wit’s most famous stories about his friend:

“It was through my professional association with George that I made my re-entry into Pittsburgh musical life… when Gershwin was invited to play the Rhapsody and Concerto with the orchestra there… We took a late train for the overnight trip, sharing a drawing room. A lengthy discussion of music occupied us for an hour or so, and I was actually in the midst of answering one of his questions when he calmly removed his clothes and eased himself into the lower berth…. I adjusted myself to the inconveniences of the upper berth…. At this moment my light must have disturbed George’s doze, for he opened his eyes, looked up at me and said drowsily, ‘Upper berth—lower berth. That’s the difference between talent and genius.’ ”

But the train trip back was delayed, because both Gershwin and Levant were busy at a post-concert party given by Mrs. Enoch (Bertha) Rauh and her son, Richard S. Rauh, the secretary of the Symphony Society. In a 1937 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article noting Gershwin’s passing, Charles R. Danver detailed the evening: “There was a buffet supper and afterwards Gershwin and Levant headed for the music room. Then began one of the most exciting piano recitals the guests had ever heard. Modern music, jazz, played by its two outstanding masters. First the composer of the Rhapsody in Blue played; then Levant played, and finally the two sat down together and turned out one duet after another. And so, far into the night. A good time was had by all—except the Rauh grand piano, which took a terrible beating. It was discovered later that the pianists had broken four of the keys!”

By the time of that visit another Pittsburgh son, playwright George S. Kaufman, had become Gershwin’s friend and collaborator. Kaufman, however, was not drawn back to his home city, as was Levant. His daughter, Anne Kaufman Schneider, in 1989 stated in the Post-Gazette that she saw little influence of Pittsburgh in her own experience of her father: “He kept saying, ‘We really should go there sometime’… but we never did.” In the early 1930s, Kaufman—with George, Ira, and Morrie Ryskind—created a trilogy of groundbreaking political-satire operettas: “Strike Up the Band,” “Of Thee I Sing,” and “Let ’Em Eat Cake.” “Of Thee I Sing” was the biggest hit of all the Gershwin brothers’ musicals, and it won the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for Kaufman and his writing cohorts (the music was ineligible). After 441 performances on Broadway, the operetta arrived at the Nixon in March 1933.

The next year, Gershwin was back as part of a 28-city concert tour with the Leo Reisman Orchestra, to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the “Rhapsody in Blue.” The Pittsburgh Press review of the February show said, “Both in this piece and his Concerto, Gershwin disclosed virtuosic command of the keyboard, and he was recalled again and again to acknowledge the sustained applause which he generously shared with his musicians and conductor.”

In February 1936, a weeklong run of “Porgy and Bess” at the Nixon won an ecstatic review by Ralph Lewando in The Pittsburgh Press: “Throbbing! Vital and human… original and entertaining.… Here, indeed, is something new—new in idiom, new in musical treatment, and new in subject matter for the lyric theater.” Lewando’s colleague in the drama seat, Kaspar Monahan, also chimed in: “As an opera… Porgy and Bess is the best I’ve ever witnessed from the standpoint of acting combined with music.”

The importance of Pittsburgh for Gershwin and his music did not end with the composer’s tragic passing in July 1937. His Pittsburgh associates continued his legacy.

Robert Russell Bennett, Gershwin’s orchestrator for many of his shows and films, produced “A Symphonic Picture of Porgy and Bess” for the 1943 season of the Pittsburgh Symphony; it was commissioned by the symphony’s musical director, Fritz Reiner, who enjoyed a long association with Gershwin.

It was Levant, however, who most prominently promoted Gershwin’s music, often in Pittsburgh. Oscar had helped George rehearse the two-piano versions of many of his major concert works, and beginning in 1932 he played Gershwin’s music at the Lewisohn Stadium concerts in New York.

Later that year, Levant began a series of appearances with the Pittsburgh Symphony under Reiner, often playing Gershwin’s Concerto in F and “Rhapsody in Blue,” as well as his own compositions, such as “Dirge-Adante (In Memory of George Gershwin)”. Levant acted in a number of movies, usually portraying a wisecracking pianist. In Hollywood’s version of Gershwin’s life, “Rhapsody in Blue” (1945), Levant played himself.

It was left to another Pittsburgher, actor-singer-dancer-choreographer Gene Kelly, to produce the ultimate homage to George Gershwin. Kelly scooped up a huge amount of Gershwin music to create one of the greatest movie musicals, 1951’s “An American in Paris.” With his major role in the film, Oscar Levant was once again in the spotlight shining from the spirit of George Gershwin.