For months last year, as the campaign for the White House shifted into high gear, opponents of President Obama tried to paint his first-term administration as hostile to the development of domestic fossil fuels, including the vast natural gas resources contained in the Marcellus and Utica shales, as well as other unconventional shale plays across the country.

As early as 2011, one coal industry official even went so far as to accuse the Obama administration of waging a “regulatory jihad” against fossil fuels. They warned that in a second term—once unshackled from the constraints imposed upon him by the need to seek reelection—he would likely give his full-throated endorsement to a host of what opponents termed “job killing regulations” that would choke off development of natural gas.

And many in the environmentalist community were privately hoping that a second-term Obama presidency would be every bit as tough on fossil fuels as the President’s opponents feared. Flush from their temporary victory last year in blocking the construction of the Keystone Pipeline that would carry tar sands oil from Alberta, Canada, to the Gulf of Mexico, but disappointed by what they saw as the administration’s willingness to compromise with the oil, gas and coal industries on a host of issues, many environmentalists hoped Obama would be less conciliatory.

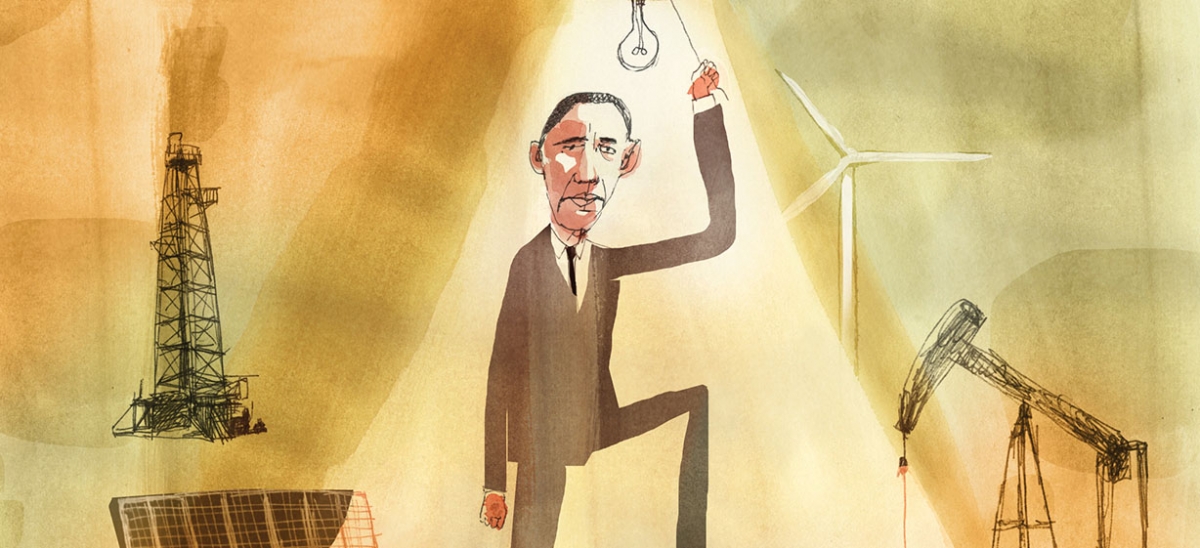

The reality, according to most analysts, is likely to be far more prosaic. In its second term, the Obama administration is not likely to be significantly different than it was in its first term. It’s likely to cautiously support the development of natural gas, both for its potential to reduce carbon emissions and its ability to help boost a sputtering economy.

“I honestly think that the administration is very divided, not just on fracking but on the whole unconventional gas revolution,” said Charles K. Ebinger, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “You have a number of people in the White House who see the job opportunities and the possibility of the President getting credit for revitalizing the economy using cheap natural gas. But on the other hand, there are people in the Environmental Protection Agency and elsewhere who say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, what are we doing here? We may be getting some short term benefits over coal with gas in terms of CO2, but in the long run we’re going to be… even more dependent on fossil fuel that we were before, and this is not going to help with climate change.’ ”

But while those divisions may be cast in somewhat sharper relief as the administration seeks a replacement for retiring EPA chief Lisa Jackson, they are unlikely to alter the administration’s moderately pro-gas trajectory, most analysts say.

The administration’s tacit support for the Natural Gas Act, which continues to face Republican opposition in Congress, remains unchanged. And regardless of who replaces Jackson after what is certain to be a contentious confirmation process, the EPA’s Toxic Air Rule, which has been credited in part for accelerating the shift from coal to natural gas by record amounts as a source of electrical power, is also likely to remain intact. So too, will the U.S. Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations—standards that will at least indirectly impact the natural gas industry, because in order to comply with its emission guidelines, an increasing number of vehicles will need to rely on the electricity it can generate.

Taken together, those initiatives bode well for the natural gas industry. But there are some other issues looming as well. The EPA is currently conducting a massive, multistate review of drilling and its impact on water quality, including detailed studies of wells in both Washington and Bradford counties in Pennsylvania and detailed projections of water usage from the Susquehanna River Basin. The report is not due until 2014, but in December, the EPA released a status report that, while it provided no details about what the EPA had found so far, seemed designed to allay critics’ concerns by going into excruciating detail about how data was being collected.

That sort of “everything out in the open” approach to the water quality study is understandable given the tensions that emerged during the President’s first term between the White House and state governments over how best to regulate and oversee the emerging industry. Nowhere was that tension more obvious than in Pennsylvania, where the White House and the Corbett administration locked horns over a number of issues, most notably over the contamination by methane—probably released by drilling—of several drinking water wells in the Susquehanna County village of Dimock. The EPA stepped in last year after the state declared the water safe to drink, and conducted its own battery of tests, ultimately concluding that the water—while it did contain elevated levels of methane—did not pose a health risk. The standoff outraged environmentalists and Hollywood activists who had flocked to Dimock, who saw it as an abdication by the EPA and the White House at large. It also infuriated the Corbett administration, which saw it as a power grab by the Obama White House.

With that episode as background, the Corbett administration remains leery about the White House’s attitude toward natural gas development. Although the President “articulated support for natural gas from an energy independence standpoint, one of our biggest concerns is that the President’s vision and rhetoric do not always align with what his EPA was doing,” said Patrick Henderson, the Corbett administration’s point man on all things energy-related. “I think going forward, one of our biggest concerns is overreach from a federal standpoint on natural gas development,” Henderson said. “When I talk about the federal government overreaching I am talking about them regulating something which they quite frankly may not have been equipped to regulate. We’ve seen the EPA ride in on a white horse and trot out with their tail between their legs on a couple of things.”

Despite that rocky history, however, Henderson believes that there may be room for a rapprochement between Harrisburg and Washington. “I think we’ve all—hopefully from the state as well as the federal government—said ‘OK, where can we focus on working together?’ Nobody benefits from an adversarial relationship. The federal government doesn’t, we don’t, and the landowners certainly don’t. We don’t want an adversarial relationship.” Instead, Henderson argued, the White House should defer to the state whenever possible, and the state needs to improve the lines of communication with the federal government. “I think information sharing—a lot of stuff that doesn’t make the day-to-day press—has been going on, opportunities to educate, to answer questions about what our state regulations are.”

If Henderson is arguing for the White House to take an arms-length approach to gas development in Pennsylvania, he is likely to get his wish, said Michael Shellenberger, president of the Breakthrough Institute, an Oakland, Calif.-based nonprofit that seeks to navigate between the partisan poles on a number of issues, including energy and the environment.

To Shellenberger, the Obama administration is going to have to continue to thread the needle when it comes to its own conflicting priorities on natural gas. “He wants to see gas production [continue] for his efforts toward [economic] recovery, and I think he’s probably going to increasingly understand gas as critical to having some climate legacy,” Shellenberger said. “I think that’s a very interesting situation. Obviously… you want to increase gas production, but that puts you at loggerheads with traditional environmental concerns.”

In the meantime, “the gas guys are always scared of the EPA coming in and shutting them down.” But Shellenberger suspects that the Obama administration will take a more arms-length approach toward both the states and the industry in a second term. “It seems like there’s a bunch of stuff happening in the states, and part of me thinks if I’m Obama or the EPA it would just be easier to say, ‘Let’s see how this stuff shakes out.’ ” There are signs, he said, that both the states and the industry, rattled by the bad press over a number of incidents including those in Dimock, are taking notice, and the administration is likely to allow that evolution to play out. “Unless it looks like the states are letting it just go crazy and all sorts of terrible things are happening, you probably want that kind of organic evolution.”

That’s not to say that the White House is likely to take an entirely hands-off approach in its second term, the Brookings Institution’s Ebinger said. “I would anticipate… that you may see [new] federal guidelines in terms of reporting what chemicals are going into fracking fluids to make that more transparent.”

But by and large, Ebinger expects that the second Obama term will look much like the first. “The debate is still out. However, I think that by the time the EPA gives a final ruling on fracking, we’re going to be up to about 50 to 55 percent of our total natural gas supply coming from fracking, and it’s hard to imagine that anything draconian would happen.”

To him, the most likely outcome is “benign neglect.” In other words, Ebinger said, despite the overheated rhetoric from the President’s opponents during the campaign, and despite the most fervent wishes of his nominal supporters, when it comes to natural gas, the second Obama term will probably be indistinguishable from the first. “I don’t think there are going to be any big changes.”