For the Joy of It

I recently read that the audience for baseball is shrinking. The author did not cite any particular franchises or cities where there were fewer fans in the stands, nor did he cite any reasons or statistics.

As someone who loves baseball, I wondered what prompted the article. Could the author have seen the proliferation of bobblehead giveaways as a way of enhancing attendance? Were more and more firework celebrations being added as inducements along with bring-your-dog evenings? Or was it something about the game itself that might explain it?

I began wondering if the baseball attendees were in some ways different from those who attend football or hockey games. If so, was it something about the games themselves that could explain this?

Leaving civic pride out of this consideration for the moment, why do different sports attract different people, i.e. attendees who genuinely are attracted by the game and not merely as a way of demonstrating their support of the “home team?” I wondered why the aforementioned author felt obliged to emphasize a decline in baseball crowds but did not point out any decline in the size of audiences for football and hockey games, where the nature of play differs radically from baseball action. The first and most obvious difference is that football and hockey, unlike baseball, are contact sports and that the contact is often violent. The field or rink is divided in half, and the aim of opposing teams is to penetrate the opponent’s territory and score. The time that is allowed for teams to do this is “clock time.” They must score before time runs out. There is no denying the territorial imperative in both sports. That alone often creates fanatic defenses. And, as I have already mentioned, the possibility of serious injury is not uncommon. Some say that this is simply part of the game. But it then permits us to ask if the attendees come primarily to witness and even relish that part of the game—the violence.

We have all seen gap-toothed hockey players (“just part of the game”), but injuries to professional football players, though not as visible, have been identified as being more serious.

Having played sandlot football and having coached a Marine Corps team during my time in the service, I found myself in agreement. Based upon corroborated statistics, it is estimated that the percentage of professional football players who retire from the game with permanent injuries to the neck and knee is 100%. Recent studies have shown that injuries from repeated concussions have affected players after retirement with corrosive brain damage, some of which have driven these players to suicide.

With these statistics in mind, I listened recently to a televised interview with Mike Ditka and Brett Favre. Both men had long careers as players, and Ditka was subsequently a coach. They were both asked if, based on their knowledge now of the multiplicity of injuries that could inevitably befall players during their careers, they would permit their sons to play football. They each emphatically said no. My presumption is that there are probably other players like them who would give a similar answer. Such answers might have little effect upon attendance to date, but I cannot help but think that eventually they will.

The glory of baseball is that injuries tend to be unintentional. A player who injures another player on purpose is penalized for doing so, sometimes severely. But what is known to all is that baseball is rife with absurdity because the rate of failure is so high. Ted Williams, for example, batted over .400 in a record-breaking season. It was and remains a record, and rightly so. But mathematically speaking, it means that six out of ten times he failed to hit safely. That’s simply the way the “ball bounces” in baseball parlance. It’s what can be expected when someone attempts to do what is universally recognized as the most difficult thing in sports—to hit with a 32- or 34-ounce bat a baseball pitched by someone who does not want you to hit it.

And even if you do hit it, there are eight players plus the pitcher who will try to catch the ball on the fly or otherwise field it and throw you out. Players who bat .300 or better are regarded as outstanding, but they fail 7 out of 10 times. I can think of no other sport where the rate of failure is so high. But for those who love to play or watch the game, the odds do not discourage as much as they tantalize and challenge.

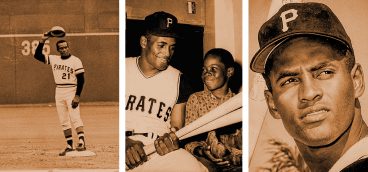

The beauty of baseball is that it makes time is irrelevant. The goal is to start from home and hopefully return. Home and back—the oldest and most basic instinct in man! Every pitch is a new game. The irrelevance of time is made even more irrelevant by the fact that the baserunners run the bases counterclockwise, further nullifying time as the game progresses. The truly observant is always ready to appreciate the instantaneous poetry of a double play (or possibly a triple play), the bullet accuracy of a catcher’s throw to second to surprise a runner attempting to steal a base, the perfect throw from the outfield a la Andy Van Slyke or Roberto Clemente to frustrate a runner-from-third’s attempt to score after a catch, the precise bunt that’s slow and unreachable enough to allow the bunter to reach first base, the rare effrontery of a theft of home by a runner who learned from Jackie Robinson that at the right time it could be done.

Played without violence and within its umpire-enforced rules, the art of baseball exists in a timeless world of its own. This may have been what prompted Moe Berg, the legendary catcher of the Chicago White Sox who spoke seven languages and had a degree from Princeton, to say that he’d rather play baseball than do anything else. It also might explain why Ichiro Suzuki, who plays baseball the way a pool shark plays billiards, keeps his bats with him in the dugout with the same care that a pool shark reserves for his cues. Joe Torre, who speaks with the wisdom of a former player and manager, says that he enjoys the way Suzuki plays baseball. He implies that Ichiro Suzuki considers his performance in the game as an art.

Contrasting football and baseball immediately reveals the essential differences. Football is a violent contest waged on land and through the air in order to gain territory. It’s a Napoleonic struggle in which strength is pitted against weakness, attacks against defenses, guile against adjustment—scrimmage after scrimmage after scrimmage. Baseball is a saga like the ODYSSEY of Homer—a timeless quest to return home after you’ve voluntarily left it. The return is all that matters, all that counts. Some returners die on first, second or third. Cyclopean pitchers use their wiles to frustrate you. You become a citizen of the Lotosland of walks. You face the Scylla and Charybdis of rundowns. But your destination is always the same, and the time it takes to get there makes no difference.

The Greeks deserve the world’s gratitude for having created the Olympics. But America is rightfully recognized as the country of origin of baseball. It’s a game that pits skill against skill in fair and overseen competition. And at its best it fulfills what the poet John Ciardi defined as the very essence of sport when he wrote: “Games are human activities made difficult for the joy of it.” The benchmark of difficulty in baseball is high, but both players and observers seem to think that the joy that comes from dealing with it successfully is worth it.