Finding Solitude in Westinghouse Park

Its pastoral charms are pleasant but unremarkable: 10 acres of well-tended lawn sprinkled with mature trees, a children’s play area and a utilitarian cement block park building. Other than the name, there is no reason to suspect that Westinghouse Park in the city’s Point Breeze North neighborhood was once the beating heart of a web of creative brilliance that extended around the world and changed it in profound ways.

Nowhere in the park is there evidence that on its acreage stood “Solitude,” the estate of inventor and industrialist George Westinghouse Jr. But the earth below has already given up crockery and other artifacts that offer a glimpse of life in Gilded Age Pittsburgh. And a neighborhood coalition is planning to look for more as it works to raise the park’s profile and preserve the memory of the man who was the Elon Musk of his day.

Rise of a serial entrepreneur

Westinghouse was already a wealthy, self-made man at age 25 in 1871, when he purchased for his wife, Marguerite, what was at the time a modest house on five of the acres where Westinghouse Park sits today.

He was born the son of a machine shop owner in 1846 in the town of Central Bridge near Albany, New York. He was only 15 when the Civil War broke out in 1861 but enlisted in the New York National Guard. Three years later, he joined the U.S. Navy as an engineer on the gunboat USS Muscoota. After Westinghouse was discharged in 1865, he returned to his family and enrolled at Union College in Schenectady, but quickly lost interest and dropped out. He had bigger ideas to pursue.

From his youth, Westinghouse demonstrated a talent for machinery. He patented his first invention, the rotary steam engine, at age 19. At 21, he invented a “car replacer” to guide derailed trains back onto the tracks, as well a reversible “frog,” a device used with a railroad switch to guide trains onto one of two tracks. He set up a plant to manufacture his products and traveled the country selling them to the railroad companies.

But inventing the air brake is what made Westinghouse rich. His air brake systems revolutionized the rail transit industry by giving engineers a quick, reliable way to stop their trains, allowing the railroads to run longer trains at higher speeds, increasing traffic and profit.

In 1869, he founded the Westinghouse Air Brake Company in Pittsburgh, where the Pennsylvania Railroad was headquartered. He had moved to Pittsburgh, a rail hub, for its low-cost steel and large supply of trained mechanics. He developed other important railroad equipment, including devices for an automatic signaling and switching system that further improved safety and efficiency, and led to another Westinghouse company, Union Switch and Signal, established in 1881.

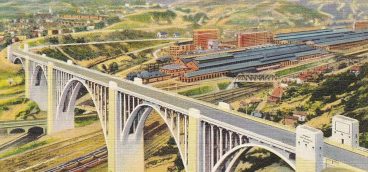

So it is understandable why Westinghouse was attracted to the house adjacent to the Pennsylvania Railroad’s mainline in the then still pastoral East Liberty Valley, between Murtland Street and Lang Avenue, six miles from downtown Pittsburgh.

Living along the rail line was a logical place for Westinghouse to settle. The railroad was his primary customer. And, with Homewood Station immediately adjacent, he had access to fast transportation both around the city and across the country.

Solitude along the tracks

Westinghouse expanded the house over the next several years. He doubled the size of his estate with the purchase of an adjacent five-acre parcel across McPherson Boulevard in 1879, giving him the entire block between Thomas Boulevard and the tracks.

He named the estate Solitude, although one wonders how serene it could have been with a steady flow of steam trains rumbling past day and night.

New construction included a stable/garage and underneath it, a suite of private subterranean workshops—his true inner sanctum. To further protect his privacy, Westinghouse had a 220-foot-long tunnel dug between his house and workshops. Beyond his property, Westinghouse had a private rail siding built at Homewood Station, where his personal railcar car was always waiting to whisk him away. He even had a private entrance through a tiled tunnel under Lang Avenue.

Solitude hosted numerous luminaries of the time, including President William McKinley and Britain’s Lord Kelvin. Regular local guests included neighbors H. J. Heinz and H. C. Frick.

Nicola Tesla spent many months in residence at Solitude working out the principles of alternating current electricity. His research led Westinghouse to become a pioneer in the development and distribution of AC electricity.

In 1886, he formed Westinghouse Electric Corporation and began a bruising competition with Thomas Edison and his direct current electricity over who would power America. Further development of AC electricity earned him the right to illuminate the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and then design and construct the power generation system that harnessed Niagara Falls in 1896 and transmission of that electricity to Buffalo, N.Y.

Lighting up the neighborhood

But the most spectacular episode that took place at Solitude was the discovery of a large supply of natural gas in three wells Westinghouse had drilled in his own backyard.

Early in the morning of May 22, 1884, the drill bit pierced a pocket of natural gas. The ensuing gusher spewed unchecked for a week before Westinghouse devised a method to cap the well. Then, to demonstrate the potential of gas, he had a flare lit from a standpipe at the top of the derrick that burned brightly for months. His high-tone neighbors could not have been pleased.

Prior to that, natural gas was considered too dangerous for commercial use. But the dozens of inventions Westinghouse developed and patented over the next two years demonstrated it could be safely harnessed, used and metered, paving the way for a new energy source for Pittsburgh and the world. His first customers included the nearby mansions of neighbors Heinz and Frick.

Westinghouse’s creative genius found many other outlets. He obtained 361 patents in his own name over his career, an average of one patent every six weeks for 41 years.

Westinghouse was as much a visionary entrepreneur and industrialist as he was gifted inventor, founding more than 50 companies. He was also a progressive thinker, particularly on labor issues. His employees worked shorter hours than was the norm, were given more vacation and were offered educational and cultural opportunities. Westinghouse paid higher wages to build a workforce of better craftsmen and engineers, and he hired the first female engineer.

His fortunes fell with the financial panic of 1907, which caught him heavily in debt and led him to lose control of Westinghouse Electric to the banks. His health also waned in the following years, and he died on March 12, 1914, at the age of 67. His wife, Marguerite, followed him into eternity three months later.

Solitude was bequeathed to their only child, George III. Four years later, he sold the property to the Engineers’ Society of Western Pennsylvania for $100,000, which the Society raised from contributions from several of his father’s companies.

A public offering

The Society transferred the deed to the City of Pittsburgh for a token dollar in 1918 on the condition the property would become a public park and a memorial to Westinghouse’s memory.

Solitude’s mansion was razed during the summer of 1919 as per stipulations in the deed transfer. The stable/garage stood for another 45 years, before being torn down in the early 1960s and replaced with a nondescript cinder block structure that has served the community ever since.

Today, three pairs of stone columns that stand at the former estate’s entrances and two flights of stone stairs that lead to Murtland Street and Lang Avenue are the only remaining vestiges of Solitude above ground, save for several copses of magnificent red oak trees, a pair of towering ginkgoes and a stately, spreading black oak.

Below ground is another matter.

When the mansion was destroyed, its fine fixtures and some structural materials were sold off, but most of the building was simply collapsed into the cellar and buried.

Solitude’s grave holds plenty of promise, as a 2005 test dig by archeologist Christine Davis revealed. Simply peeling back the sod over a small corner of its foundation uncovered hundreds of historic artifacts, including shards of stained glass, pieces of kitchen crockery and perfume bottles.

And there’s more. When the stable building was torn down, no record was made of what happened to Westinghouse’s suite of private laboratories underneath, but there is evidence to suspect that at least some rooms are still there. A survey conducted with electromagnetic detection and ground-penetrating radar last fall revealed more than a dozen “anomalies,” inviting deeper exploration.

Most enticing is the 220-foot tunnel that Westinghouse had built between his house and his inner sanctum of workshops. The tunnel is still there, beehive shaped and brick lined, eight feet high and five feet wide at the base. And it is entirely intact.

Preserving the past

On the eve of the park’s centennial last year, a group of neighbors and others organized the Westinghouse Park 2nd Century Coalition to enable the park to further blossom. It took on the role of steward of the park, with a mission of enhancing its existing amenities; exploring, documenting, and presenting its rich historical bounty; and honoring the memory of George Westinghouse.

With the support of Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto’s office and city Councilman Ricky Burgess, the group has begun work to unearth the park’s mysteries, starting with the recent deep peek into its tunnel. An ongoing archeological investigation of the relic-rich troves where the mansion and stables stood is planned. It’s part of an effort to raise the profile of the park as a public gathering place and awareness and appreciation of Westinghouse who, in his last words, said: “If someday they say of me that in my work I have contributed something to the welfare and happiness of my fellow man, I shall be satisfied.”

Follow Westinghouse Park at www.westinghousepark.org.