Explaining Donald Trump, Part III

I’m claiming to be able to explain Donald Trump—and predict his actions as President—by reference to only two of his characteristics. The first is that he’s what I’ve called a Mega Entrepreneurial Personality, a trait he shares with an infinitesimally small group of Americans.

The second trait is something Trump shares with almost all of us: he’s never held elective office. In fact, 98% of us have never held office (that’s the exact percentage, by the way).

The first reason this characteristic is important is because Trump—as would be the case with any of us non-officeholders—isn’t familiar with the ways of Washington, D.C. and doesn’t much know (or, more important, trust) anybody who does. Say what you will about people who have spent most of their time inside the Beltway, but they at least know how the place works, what do to and not to do, where the landmines are buried, which apparently innocent activities will, in fact, get you crucified.

Neither Donald Trump nor anyone in the trusted circle around him knows anything about all this. They are babes in the woods and every which way they turn they are stepping into the you-know-what without meaning to. Simple undertakings that, in a corporate context, would be routine no-brainers turn out, in the hothouse environment of Washington, D.C., to cause outrage and consternation.

Much of this is just Beltway nonsense and violating those kinds of rules, while jaw-dropping to insiders, is ultimately harmless and probably mostly to the good. Washington does need to be shaken up now and then, whether it’s by Barack Obama from the left or by Donald Trump from the right. But Washington is also the way it is for sound reasons: running a representative democracy on behalf of 330 million people is a very different thing from running your own private corporation.

If you are meeting with a business ally and want to solidify the relationship, you could do worse than confide in them some piece of confidential information that will help them out and, by the way, wow them with how knowledgeable you are. Try that when you are the President of the United States and the confidential information is Top Secret intelligence out of Israel and the wrath of God will come down on your head.

If someone who works for you at The Trump Organization has not only lost your confidence but has even energized your competitors with his behavior—in other words, the guy is a complete bozo—you simply fire him and get on with your life. But if you are the President of the United States and the guy is the Director of the FBI, you wake up to find yourself hounded by an independent prosecutor.

The second reason why Trump’s never having served in office is important is because he’s managed to live a long life (he’ll be 71 in a few weeks) and over all those years he has—like the rest of us—developed a long list of firmly held opinions, not a single one of which has ever had to be tested in the crucible of public policy debate. When a man with an MEP personality collides with a world in which his opinions don’t much matter, what’s likely to happen?

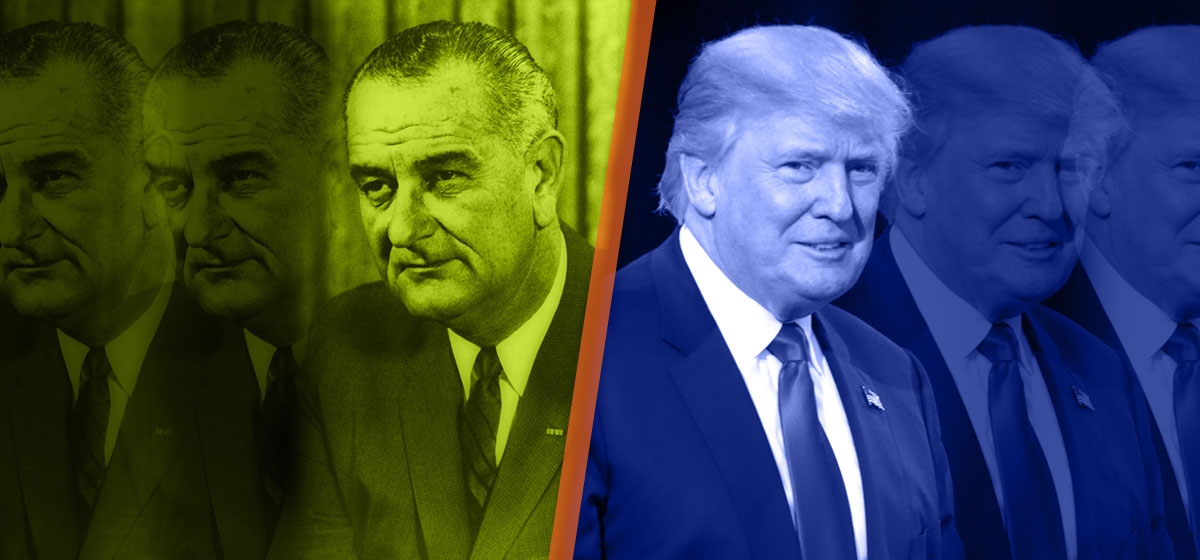

An interesting way to think about this is to compare the career of the American President who, at least during my lifetime, was the most MEP-like: Lyndon Johnson. LBJ was a huge man in almost every sense of the word. Among other things, he dominated the U.S. Senate—not exactly a coterie of retiring violets—for a decade by the sheer force of his personality and is widely considered to be the best Senate leader in history.

Johnson’s most famous weapon was the MEP-like assault known as The Treatment, via which Johnson would corner some hapless Senator whose vote he needed and, using “supplication, accusation, cajolery, exuberance, scorn, tears, complaint, and the hint of threat,” Johnson would render the victim of The Treatment “stunned and helpless.” (As described by Evans and Novak in their book on LBJ.)

The key difference between LBJ and Trump is that LBJ served in national elective office his entire adult lifetime. He was an enormously forceful man, and he certainly held a lot of opinions, but he knew only too well that his opinions were worthless unless he could convince a majority of legislators to agree with him.

At his best, LBJ was an incomparable politician. When he focused on being President of all the people, he could accomplish almost anything—consider his signature achievement, passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But when LBJ was in pure MEP-mode, imagining that he could accomplish the impossible and that he was right and everyone else was wrong, the results could be very, very bad.

The best example is Johnson’s belief that he could win the War in Vietnam and abolish poverty via his Great Society programs, both at once. As it happened, both were impossible—let alone either one—but Johnson was operating behind an impenetrable reality distortion field.

That reality distortion field would eventually slam into the brick wall of undistorted reality. In the spring of 1968 Eugene McCarthy did unexpectedly well in the New Hampshire Democratic primary and was polling strongly in Wisconsin. It was suddenly clear that the country had lost faith in Lyndon Johnson and he was forced out of the Presidential race, opening the way for Republican Nixon’s victory in the fall.

If an MEP who’d been in political office most of his life, and who knew the wicked ways of Washington better than almost any man alive, still managed to destroy his Presidency, what might we expect of Trump, who knows little about Washington?

We’ll look into that fascinating issue next week.

Next up: Explaining Donald Trump, Part IV