Wheeling v. Pittsburgh

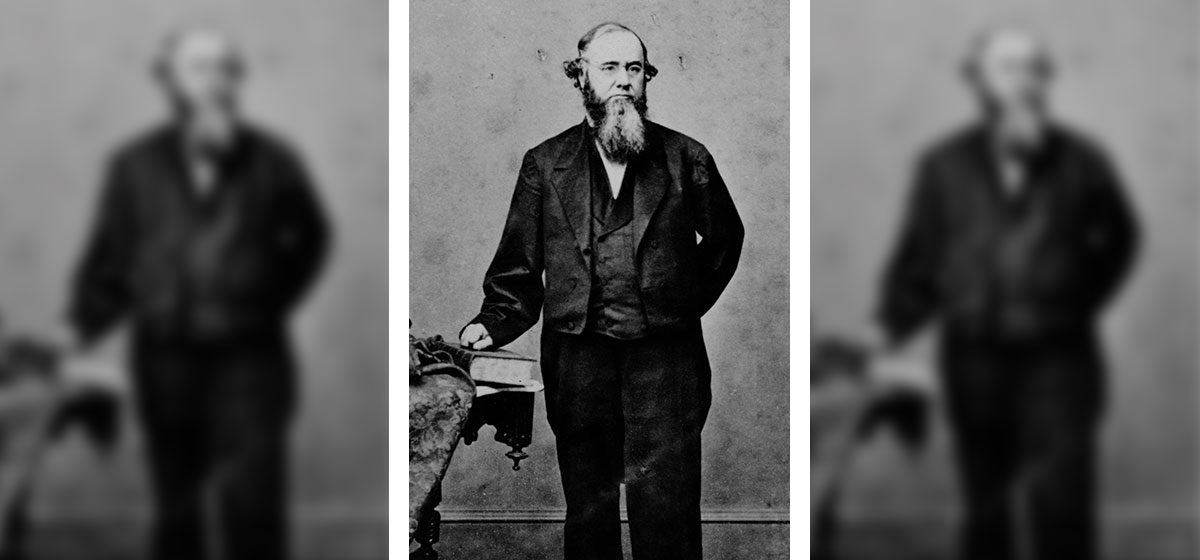

Now he belongs to the ages.” Those famous words were uttered by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton as the last breath of life fell from the lips of Abraham Lincoln.

With the murder of Lincoln, the task of reconstruction would take a very different face and raise political retaliation in the U.S. to a fever pitch. Secretary Stanton would play a Goliath role in the political fallout after President Lincoln’s death. That fallout and his uncanny ability to make enemies shaped history’s view of the man, a view that is only recently emerging from clouds of rumor and innuendo.

Whatever legacy historians place on Edwin M. Stanton from a political perspective, it does not alter one critical fact. Attorney Stanton practiced the bulk of his profession in Pittsburgh and argued and won the most influential U.S. Supreme Court decision in the history of—and in favor of—Pittsburgh.

Born in Steubenville, Ohio in 1814, Stanton was enrolled at Kenyon College, but he was compelled to leave early in his sophomore year to help support his family after their finances unexpectedly crashed. Faced with this daunting challenge, Stanton then set about to secure a “Lincolnesque” education; first in Columbus and then back in Steubenville. Securing his legal education under a preceptor in Steubenville, Stanton passed his bar examination in 1835 and turned to practice law in Cadiz, the county seat of Harrison Co. Ohio, which became better known as the birthplace of George Armstrong Custer and Clark Gable.

By today’s standards, Stanton would be known as a workaholic. Relentless and remarkably successful in his profession, he looked beyond Ohio and in 1847 turned his attention to the more lucrative legal market of Pittsburgh. He would remain in Pittsburgh for a decade and secure the city’s standing as the “Hub of Western Commerce.” In 1847, Pittsburgh boasted a population of almost 50,000 and of course, three rivers. While the lock and dam systems of today did not exist and the rivers (most notably, the Ohio) were not navigable all 12 months, the Ohio River served as the interstate highway of the era and allowed for the transport of goods, materials and people in the most cost- and time-efficient manner of the day.

Try to imagine the chaos that would ensue if you were driving along Interstate 79 and suddenly, as you entered West Virginia, the level of the overpasses dropped by several feet. The number of truck crashes would be staggering. That scenario played out in the 1840s, but instead of interstate highway overpasses, it involved a bridge that spanned the Ohio River at Wheeling.

The now-obscure Wheeling Bridge case was one that would prove to be pivotal in the fortunes of Pittsburgh.

The players were the commonwealths of Virginia and Pennsylvania, the State of Ohio and the U.S. government. To bolster their economic influence, Virginia and Ohio chartered a company to proceed with a clever and grand scheme. Ohio and Virginia would create a private company to build a bridge along the present-day Route 40 (the National Road) that would cross the Ohio River from Wheeling, Va., into Ohio (West Virginia would not become a state until 1863). In addition to providing greater ease of transportation by coach and horse, and being poised to feed the ever-growing railroads, the bridge would have a fully intended yet devastating consequence to all ports sitting above Wheeling. Its deck was to be so low that river boats could not pass beneath it because of their high smokestacks.

Foiled by the inability to secure enough private financing, the company turned to the U.S. Congress, which appropriated federal funds to build the bridge. The political clout of Pennsylvania, however, defeated the effort and stopped the Congress from agreeing to fund the project on the grounds that the suggested level of the deck—90 feet above water level—would not allow the passage of steamboats with tall chimneys. Undaunted, on March 19, 1847, the Virginia legislature authorized the erection of a wire suspension bridge, subject to change in design, in case it should obstruct the navigation of the Ohio “in the usual manner.” Construction on the bridge began.

Deprived of the ability to transport materials and goods to market, Pittsburgh’s burgeoning industries would flounder. Already cut out of the National Road sweepstakes, Pittsburgh’s river traffic would now be strangled by the low deck of the Wheeling Suspension Bridge. With fortunes on the line, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania opened its wallet and hired a Pittsburgh lawyer, Stanton, to represent it before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Virginia built the bridge, and in 1850 Stanton argued before the Supreme Court for an injunction to remove or change the bridge. His argument was simple. The rivers were navigable routes and free to citizens of all states, including Pennsylvanians; construction of a bridge with so low a deck would cause irreparable injury to those above stream. He supported his argument with the fact that when he chartered the steam boat Hibernia and raced her beneath the Suspension bridge, her stacks ripped away and caused the Hibernia to collapse. Foreshadowing its looming secession, Virginia argued that it exercised exclusive sovereignty over the Ohio River.

Stanton prevailed, and over the next few years, the bridge was subjected to various court orders that ultimately raised the level of the bridge in lieu of making it a draw bridge. Likewise, Pittsburgh’s standing as the Hub of Western Commerce was secured, and the Civil War would propel it into an industrial giant.

The Wheeling Bridge case crystallized Stanton as an attorney with few peers and a specialist in matters involving federal law. With a substantial practice before the U.S. Supreme Court, he moved in 1856 to Washington, D.C.

In 1860, President James Buchanan appointed the nationally known and highly successful Stanton as attorney general. It proved fortuitous for the Union, as Stanton advocated against secession and stopped many last-minute moves of capitulation by the Buchanan administration, including the surrender of Fort Sumter.

The election of Republican Abraham Lincoln would normally have meant that Democrat Stanton would be job hunting. But these were no ordinary times, and Lincoln was no ordinary president. While Stanton is most widely known for his pivotal role as Lincoln’s secretary of war during the Civil War, his appointments continued after Lincoln’s death. Stanton served as secretary of war to President Andrew Johnson, though he despised Johnson’s reconstruction policies and resigned only after the Senate failed to convict Johnson in impeachment proceedings.

Appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant to the Supreme Court on Dec. 20, 1869, Stanton was confirmed by the Senate the same day. Stanton, however, died on Christmas Eve, before he could take the oath of office. And the lack of taking the oath has relegated Stanton to a footnote on the list of Supreme Court justices.

Of the many icons of Pittsburgh history, none is as simultaneously relevant and obscure as Edwin M. Stanton. He understood the importance of interstate transportation and the role the rivers would play in Pittsburgh’s destiny. And he possessed the acumen to carry the day when called upon to advocate Pittsburgh’s needs.