Destination of Choice?

Seemingly overnight, China has become the destination of choice for American companies looking to expand their operations overseas. In 2004, China surpassed the United States for the first time as the top worldwide destination for foreign direct investment.

For 2005, that should equate to about $58 billion. In the western Pennsylvania region alone, there are seven major corporations which have made significant investments in China, and another dozen are right behind. Some have made money; others have not—yet.

If you look back over the last 20 years, many businesses that ventured into China have found it a tough place to compete. While I have spent my career helping companies with their operations in Asia and elsewhere, I wanted to share with those who are now thinking about China some basic but critical considerations.

Much has been written about the politics of Taiwan and the buildup of the Chinese military on the Mainland. Will China and Taiwan go to war any time in the foreseeable future? I believe the answer is clearly “no,” and the reason is economics. What will surprise most people is that the largest investors in the People’s Republic of China are those Chinese sitting in Taiwan. If you look from Taiwan directly across the narrow strait at China, you see Fujian Province, which has emerged as one of the major growth areas in China over the last 15 years. Most of the investment in the Fujian Province is from the Taiwanese. While it comes in indirect ways, such as being invested in offshore companies and eventually winding its way around to China, it is nevertheless Taiwanese money. Over the last year the Opposition Party in Taiwan has actually traveled to China for meetings with top Chinese leaders. This surprising political connection along with the vast sums invested make it highly unlikely in my view that a war will erupt there.

If you assume the Chinese economy will continue its current growth rate, it could surpass the U.S. economy within the next 20 years. However, China faces three very daunting challenges, any one of which could significantly halt the growth of the Chinese economy and thus its attractiveness to foreign investors. In doing a risk analysis as an outsider, every company should carefully evaluate these challenges before making any investment in China.

First, and most fundamentally, China is sharply divided into a “rich China” and a “poor China.” Looking at a map of China, you will see along the eastern coast a string of cities that you recognize and some you might not: Shanghai, Beijing, Xiamen, Shenzhen, Guangzhou. Within that strip is where most of the Chinese industrialized growth has occurred over the last 25 years. In a very general sense, you will find about 400 million people who on a per capita basis are earning the equivalent of about $2,500 a year. What is left then are the 900 million people located in the central, southern and western regions of China. Comprising the “poor China”, most are dependent on agriculture and have a per capita income of about $500 a year. This is China’s greatest threat. With the advent of the Internet and cable television, what would you do if you saw some of your fellow countrymen making three to five times as much money as you? The answer is, you would move. There is an increasingly strong social and economic pressure for Chinese in the poorer agricultural areas to transplant themselves toward the coastal cities. The Chinese government realizes that this cannot be allowed to happen, otherwise there will be chaos. As a result, the Chinese government is creating tax incentives for foreign investors encouraging them to look inward toward lesser-known cities such as Harbin, Wuhan, and Chengdu. As the rising tide of expectation grows, though, no one knows if the Chinese government will really succeed in halting a mass migration to the large cities.

The second major challenge China faces has to do with energy and pollution. China is one of the most polluted countries in the world, and things are getting worse. Whether you travel to the back woods, the cities, or the countryside, whether in Beijing or Shanghai, you will encounter significant water and air pollution. One of the main causes of this pollution and an underlying threat to China is its voracious demand for energy. In order to fuel its vast manufacturing sector, China needs reliable sources of energy. Even today, the source of about 70 percent of China’s energy is coal. While China has vast proven reserves of coal, most of it is filled with sulphur, which produces severe pollution, and is located a long distance away from the major manufacturing centers along the coast. Any city you visit in China periodically experiences “brown outs.” When you see the wonderful tourist photos of Shanghai with twinkling lights at night, it is truly beautiful, but even Shanghai has energy problems.

The real question is whether China will be able to create enough infrastructure to meet its ongoing demand for power. Even if its growth stopped today, China needs to build for the next five years to meet current demand. When you factor in that the Chinese economy is growing at between 8% and 10% per year, you can just imagine its future needs. What also worries the Chinese is how the U.S. is reacting to its attempts to spend their currency reserves (to a large extent, U.S. dollars) in international markets. For example, the Chinese were shocked when the bid for Unocal by the Chinese National Overseas Oil Corporation (CNOOC) was rejected by many in the U.S. Congress and much of U.S. industry.

The fact is that China is now a permanent and direct competitor for energy resources with the United States across the world. It consumes about 6.3 million barrels per day and has to import at least half of it. How the United States handles this, and China’s growing energy needs, will do a lot to determine the future relationship between the two countries. Those who know anything about U.S. history will remember that part of the rise of Japan and its military leadership during the 1930s was a direct result of American and European efforts to cut back on Japan’s sources for energy and raw materials as Japan sought to grow into a larger economic power.

The final challenge is in many ways the most difficult to deal with because it involves the Chinese people. The Chinese government made a pact with its people over the last 20 years that it would allow increasing amounts of economic freedom and the ability to set up nonstate-owned businesses in exchange for continued tight control over political freedoms. Recently, however, the Chinese government has gone beyond just cracking down on dissidents — it has directly approached major Internet providers and insisted that those providers not allow certain key search words and sites to be provided to the Chinese. Although this has received very little attention in the American press, it is a significant development. There is also a semireligious group in China called Falun Gong (aka Falun Dafa) which has been suppressed by the Chinese government. The United States is now going around the world promoting freedom and democracy, but will it stand by such strong statements regarding these policies with the Chinese? If it does, it will clearly put the U.S. and China on a collision course. What the U.S. must decide regarding its future relationship with China is whether it will insist upon promoting civil freedoms or if global economics will take precedence.

What all of this means is that when any company looks at China for the first time and recognizes that it can do things less expensively there than in many other countries, it needs to factor in the three big-picture items I just discussed. No one, regardless of their amount of experience in China, really knows what the future holds. When Richard Nixon in 1970 said China had to open itself up to the world and the international community, China set itself on a new course from which it cannot reverse. Only time will tell where that will lead.

An American lawyer in China

Twenty years ago I visited China for the first time, and my view of the world changed forever. This took me by surprise. I had studied China at the University of Virginia as part of a lifelong fascination with the country and its people, and I mistakenly thought I “understood” China. I came to realize that it is a very long way from Pittsburgh to Beijing in more ways than one.

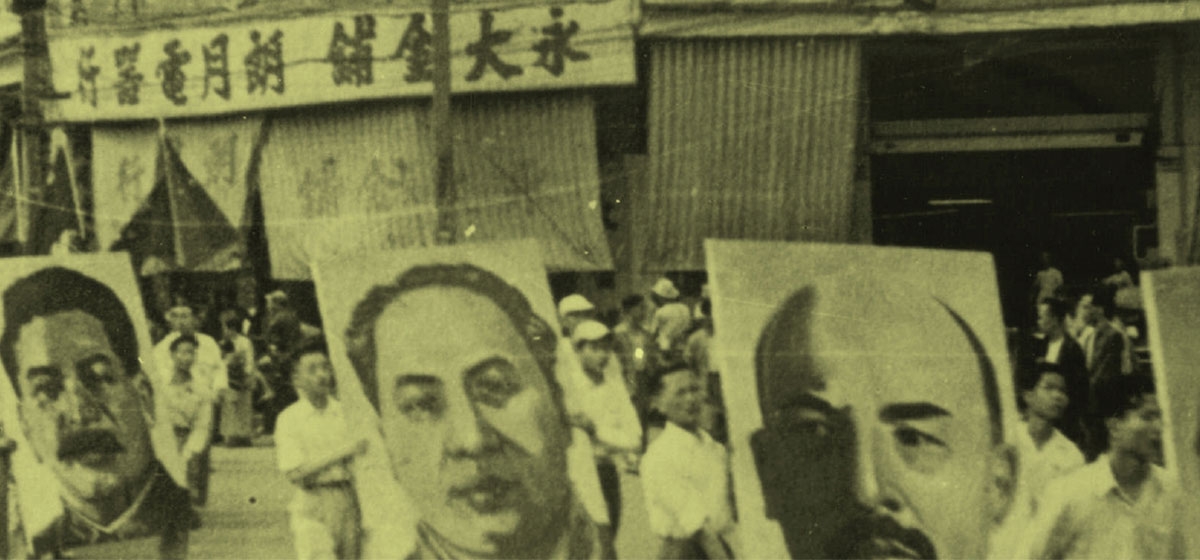

Over dozens of trips since then, I have learned that there is really no one definable China. My favorite Chinese saying is “We are in the mountains and the Emperor is far away.” This reflects a simple reality that the more removed one is from China’s central government, the more diverse things become. Beijing is a typical political city with overwrought buildings in the Mao/Stalinist 1950s style exuding an atmosphere of control. A mere 90-minute flight away is Shanghai, perhaps the fastestgrowing city in the world. The people there are confident, aggressively commercial, and literally a world away from the government capital of Beijing. To the south lies the Pearl River Delta, which stretches from Guangzhou (Old Canton) to Shenzhen to Hong Kong. Since the early 1980s, this region of 42 million people has exploded into the manufacturing heart of China. Much of what was once produced in America’s Midwest now comes out of thousands of factories populating the Pearl River Delta. Standing alone, it is the 16th largest economy in the world. They even speak a different language (Cantonese), and their attitude toward life and business is unlike anywhere else in China. If you travel west to Kunming (which is north of Vietnam), you encounter a China with a distinctly Southeast Asian flavor. These vast regional and cultural differences made me realize that in order to interact and successfully do business in China, I had to constantly adapt to diverse local needs and customs. This is a never-ending challenge. After 20 years, I still learn something new on every trip.

During every visit to China, its raw energy slaps me in the face. It reminds me of my grandfather who came to America as an impoverished immigrant from Yugoslavia in the early 20th century. As a child, I remember looking through his scrapbook of old black-and-white photographs of Pittsburgh that graphically portrayed the smoke, soot and heavy pollution that accompanied the city’s steel production. The biographer James Parton once described Pittsburgh as “Hell with the lid taken off.” Chinese cities of today, like Wuhan or Harbin, closely resemble those old photos of Pittsburgh 50 to 80 years ago. I quickly discovered that most of China is not postcard-beautiful—it is chaotic and the pollution is shocking. But underneath China’s drive to grow reflects a fierce vitality and challenge to those who want to compete within the Chinese economy. Halfway attempts are doomed to fail—China demands your best efforts.

Another lesson I have learned is that nowhere in the world is “face” more important than in China. Again and again over the years, I have seen the consequences of thoughtless actions by Americans, inadvertent or not, resulting in embarrassment to someone and thus causing loss of face. An intuitive understanding of the concept of face is why the Chinese are among the best negotiators in the world. Face is universal, but understanding how the Chinese use it to their advantage forces everyone else to step up and do the same.

Perhaps my most personal lesson in China was the most unexpected. Western Pennsylvania is a geographic region with a relatively small minority population. Unlike the 19th and early 20th centuries, there has been limited immigration here over the last 40 years. On my first trip to China, I remember walking down a busy street and feeling lost in a sea of humanity. It was the first time in my life when I looked around and realized that I was the only white face anywhere. It struck me then, and I have never forgotten, what it means to feel like a minority. This has sensitized me to what it must be like to live in a society where people are always looking at you as an outsider.

My business travels to China over the years have opened my eyes in so many ways, and now I look at my two university-aged children who are just beginning to contemplate their professional lives. The challenge facing them and the rest of their generation is stark. The U.S. today counts for 6% of the world’s population, yet it controls over 40% of the world’s wealth. Everyone outside of America wants what we have and are finding new ways to get it. Only through hard work and the better education of our children will America be able to meet this future competition and maintain our standard of living in the coming years. China, for example, graduates nine times as many engineers each year as the U.S. In this vastly competitive arena, it is the growing economies like China and India that pose the greatest challenge to America’s prosperity. We need to look at how the world really is if we want the next generations to do as well as we have.