Democracy, Populism, and the Tyranny of the Experts, Part VI

Populism is an unsettling phenomenon in part because we don’t know where it will end. And we don’t know where it will end because populism isn’t itself a governing idea—it’s a response to the perceived failure of other governing ideas.

On the other hand, looking back through history we can notice—as a matter of observation, not necessarily causation—that populist revolts tend to take somewhat predictable paths. When the revolt is targeted against a government composed of hereditary elites, the outcome has tended to be an authoritarian government of the left. We saw that in Russia, China, France (the Commune), Cuba, and so on. On the other hand, when the populist revolt is targeted against a weak democracy, the result has tended to be an authoritarian government of the right: Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal.

Mostly, populist uprisings don’t actually amount to “revolts,” but to something less; call them populist “uprisings.” The U.S. has had many populist politicians (from the left and right) over the years, although mostly at the state and local level. Consider Pat Buchanan, William Jennings Bryan, George Wallace, Huey Long, maybe even John Edwards. But more typically, as politicians have moved ever closer to the pinnacle of national power, they have tended either to move toward the political center or not to get reelected.

More recently, though, this pattern seems to be breaking down. As David Brooks has pointed out, Barack Obama’s politics were further from the American political center (to the left) than any successful Presidential candidate in history. And once the pattern was broken, other extreme candidates rushed in—most notably, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump.

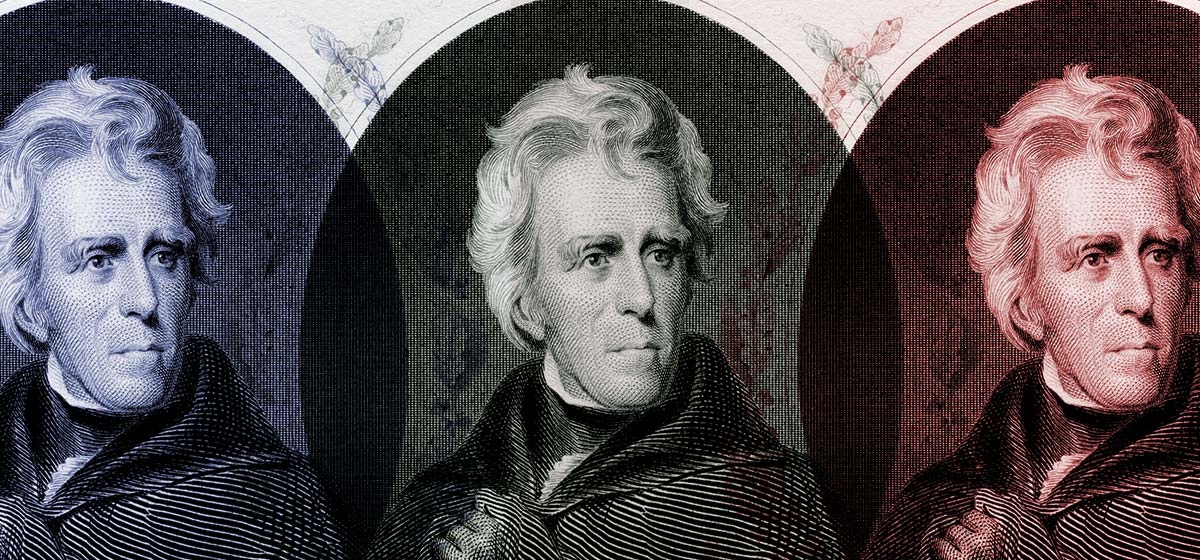

This raises the question of where populist uprisings might lead in the U.S., and one way to look at this question is to go back nearly 200 years to the career of Andrew Jackson—the only President before Trump who might be considered to have been elected as the result of a populist “uprising.”

One interesting thing to observe about Jackson is how consequential his Presidency was. Despite the opposition of every political party, the mainstream media of the day, and the governing elites in finance and government, he served eight years and enacted much of his populist program. Among other things, Jackson weeded out corruption, reduced the power of banks, paid off the national debt (the only time in history this has ever been done), oversaw the demise of the Second Bank of the United States, and threatened military force against South Carolina when it hinted it might secede from the Union. In his spare time he founded the Democratic Party.

More important for our purposes is the fact that Jackson was the first true democrat in Presidential office. Prior to him, power in America had resided in a small, affluent, well-educated elite, harkening back to the elites that had launched the American Revolution and founded the country. But over the ensuing four decades that elite had degenerated into a narrow, corrupt, venal group pushing almost nothing but its own interests.

The way Washington worked in the so-called Era of Good Feelings was (and this is only a slight exaggeration) that revenues would flow into Washington from excise taxes, tariffs, customs duties and land sales and the spoils would be divided among the governing elite and their cronies. Out of nowhere Jackson landed, as Ellen Goodman might have put it, like a karate chop on this weary little world of degenerate elites.

The Jackson phenomenon was so startling it had a name: “Jacksonian democracy.” Prior to Jackson, democracy in America was a somewhat theoretical conceit. It didn’t include women and African-Americans, of course, and it didn’t include most men, either—only those who owned property. Our modern-day focus on civil rights, though, has caused us to lose sight of how crucial the Jacksonian breakthrough was.

Although America didn’t have the rigid social classes of 18th century England, it had been founded by elites, many of whom had inherited their high place in the world. “Jeffersonian democracy” insisted on eliminating the heritability of power, but it substituted education for birthright. Under Jefferson’s view, the U.S. would be governed by an educated, “enlightened” elite. The requirement that a man own property in order to vote was, in essence, a proxy for Jefferson’s new aristocracy—if you were a property owner in the late 18th and early 19th century, you were almost certainly an educated man.

It wasn’t until the arrival of the populist Jackson that the property requirement was eliminated and essentially all men were allowed to vote. (Assuming, of course, that they were white.) Jefferson had eliminated inherited elites, but it wasn’t until Jackson that elites were eliminated altogether. Eventually the franchise would be extended to African-Americans and women, and suffrage would be universal.

Jackson succeeded in the face of high odds because he harnessed the power of ordinary people—farmers, working families, westerners—who had long been ignored, exploited and patronized by a wealthy, well-educated, and seriously out-of-touch elite. If this sounds familiar it’s because Donald Trump, for better or worse, followed the Jacksonian model to the letter. But instead of trying to shove aside a wealthy and well-educated elite, Trump and his supporters were up in arms about a very different version of the problem, namely, the tyranny of the experts.

Just as the elites in Jackson’s era had dominated ordinary people for three or four decades before Jackson’s election, our modern, elite experts have dominated ordinary people for three or four decades, as contemporary life has become ever more complex. The difference today is that our elites don’t just dominate Washington, D.C., elite experts dominate every aspect of modern American life.

And there’s another difference from Jackson’s day as well: today’s problem can’t be resolved at the ballot box, as I’ll demonstrate next week.

Next up: DP&TE, Part VII