Dear Mr. President

My stepson worked in President Obama’s mailroom when he was in college. He referred to it as the “mailroom of the free world,” which made Jeanne Marie Laskas burst out laughing. She had never heard anybody say it that way. Though my knowledge of the minutiae of my stepson’s days there is scant, Laskas wants to know more and asks follow up question after follow up question to what I simply meant to be an ice-breaker. I’m interviewing her, but I find myself doing more of the talking. She sits there absorbing, nodding and saying things like, “Oh, that’s so interesting.”

It is easy to see why Laskas is such a good writer: she is an intense listener.

A distinguished professor and founding director at the Center for Creativity at the University of Pittsburgh, Jeanne Marie Laskas writes some of the best non-fiction you can lay your hands on for publications such as the New York Times Magazine and GQ. Her books include “Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work” (Putnam, 2012) and “Concussion” (Random House, 2015.)

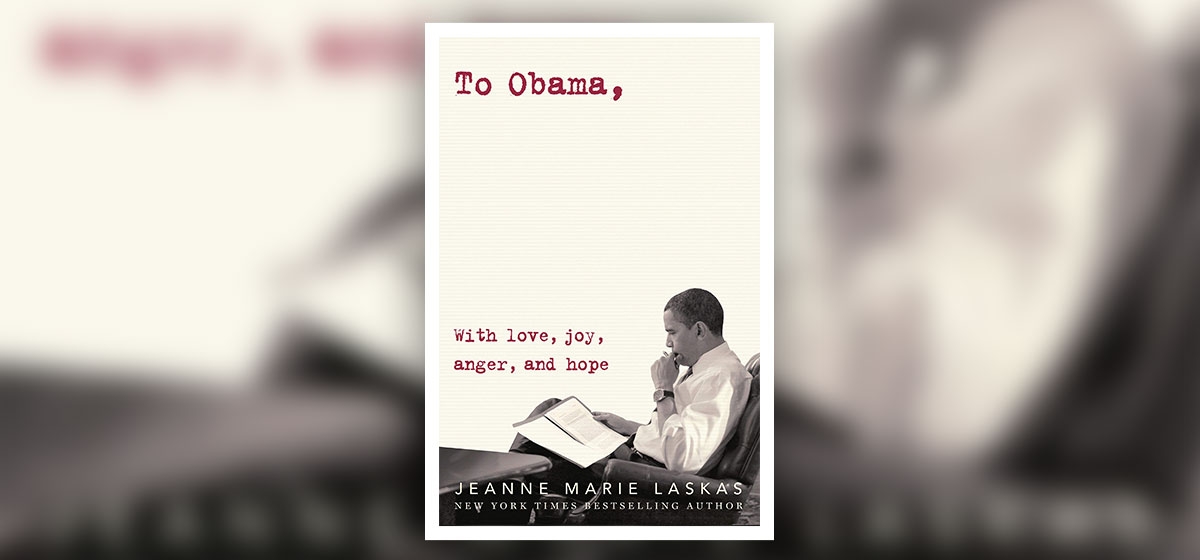

I brought up the White House mailroom because we’re sitting down to talk about her most recent book, “To Obama: With love, joy, anger, and hope” (Random House, 2018), which does a deep dive into constituent letters sent to President Obama and the Office of Presidential Correspondence (OPC), which handled those letters. Obama wanted to stay in touch with citizens and wanted to read 10 of their letters a day. Other presidents read mail, at least bits and pieces of it, but this volume was unprecedented and new infrastructure was put in place to accommodate such a high level of engagement.

The letters that got through to the team—the ones selected for the 10 Letters a Day (10LAD) list—told stories. Critical letters were not excluded. Whether negative or positive, stories of suffering, triumph—deeply personal stories—were gold.

“This is what Obama was asking for,” Laskas said. “He wanted the stories as opposed to the raw data or the charts or the polls that would indicate trends. He wanted the meat. That’s what the book then, tried to do, too. You get a perspective on the human being holding that office who has explicitly asked for human beings to come through, somehow.”

Pete Rouse, Fiona Reeves, Yena Bae, Kolbie Blume and many other people in the mailroom built mechanisms to read, sort and process the mail to bring Obama’s rough idea to life. Reeves culled the letters down to the 10LADs and those were passed on to the president in a folder at the end of the day.

Bobby Ingram wrote to Obama in April, 2009, during the worst months of the financial meltdown. He was a land surveyor and his job, like so many jobs related to real estate, just vanished into the air courtesy of a reckless lending market.

Laskas writes this about Ingram writing to the new president: “Extending his hand. That was hello. That was: It’s me. The guy who used to have calluses. Middle- to lower-class. Not so much education. That guy. Who is also —this guy. Curious, constantly questioning, a self-taught renaissance man. An enigma. A contradiction. I’m both guys. ‘I am large, I contain multitudes,’ Walt Whitman said. Don’t forget that, Mr. President: multitudes.”

There were many others, such as Ashley, who wrote when her family is in deep crisis, Thomas and JoAnn, whose daughter died in the World Trade Center on 9/11, and Marnie, a struggling teacher on Long Island. Laskas spent time with letter writers and talked to them about their their day to day lives. What does a typical morning look like? How do you fill your time? What makes you happy? What makes you nervous? Laskas is the Lebron James of this kind of writing. Each profile is elegant and deeply human, which is to say, complex, alive, troubling and inspiring. “To bring that kind of character to life—that’s what I love to do,” Laskas said.

It felt like the act of writing a letter to the president was transformative for everybody involved. The president and the staff were moved by the letters. And writing transformed the letter writers themselves. Laskas always asked the authors of the letters what moved them to write to the president. “First of all, to me, when I first started this project, I was like, who writes to the president?” Laskas said. “It would never occur to me to do that. So often, I heard that same story of someone—at a moment of desperation or needing to just shout into the wind, but it was to the president and don’t even expect him to get it. It was almost like a prayer.”

We talk about a lack of hope and positivity. We talk about a lack of civility and, just as importantly, a lack of depth. Laskas is always looking for a way to connect with a subject, to find the authentic in a world where conversation isn’t driven by tweeting the cleverest drollery first or posting the quickest hot take to Facebook.

That was the point of the letters, too. That listening could be one’s core value. What comes through in the book is that the OPC staff were committed to reading (listening to, really) constituent mail as an act of service; an act of patriotism, in a way.

Laskas found the letters to be songs of hope, something to hold onto. “It gives you hope of the citizenry,” she said. “I feel like this book is that. You do get hope because, we’re all in this together, this country. You see these moments of people like that rising up. Just because the president said, ‘go ahead, write to me.’ Democracy is alive and well with the citizenry, no matter who our president is. That’s what I hold on to. I do. I have to.”