The year was 1955, the place the long bar at the Carlton House Hotel. Standing as bookends were Pirates sportscaster, Bob “the Gunner” Prince and KDKA newscaster, curly-haired Bill Burns. Both men were serious drinkers, but the Gunner, resplendent in a canary yellow blazer with an ever-present screwdriver in hand and another waiting in the on-deck circle, was besting the anchorman two to one.

The hum of the conversation warmed as much as the alcohol. The Pittsburgh Renaissance was near high tide, and David Leo Lawrence was Mayor.

David L. Lawrence (1889–1966) is the foremost political figure this city has produced. He was one of America’s major political bosses and machine politicians in a select triumvirate with Boston’s James Michael Curley (1874–1958) and Chicago’s Richard J. Daley (1902–1976). Lawrence lacked the talent and intellectual capacity of the flamboyant Curley, although, unlike Curley, he never logged any jail time. The closest parallel is with the jowly and ham-fisted Daley. Both were political bosses throughout most of their careers accepting the mantle of high political office only deep into middle age. Lawrence was elected mayor of Pittsburgh in 1945 at age 56; Daley became mayor of Chicago in 1955 when he was 53.

Lawrence’s grandfathers, Isaac Lawrence and Charles Conwell emigrated from Ireland shortly after the mid-century potato famine. Both families settled near the Fort Pitt Blockhouse, becoming part of an ethnic subset known as “Point Irish.” In 1880, Charles B. Lawrence, Isaac’s second son, married Catherine Conwell, the third of nine girls. David Lawrence, the youngest of four children, was born in 1889. The Lawrence family was working class; they lived a modest but comfortable existence. Catherine Lawrence was the dominant figure in the household, devoting her energies toward daily observance of her devout Catholic faith. She was no Margaret Carnegie and gave little thought toward upward mobility. Her family life was stable and cohesive; she wanted her children to replicate it by emphasizing employment over education.

David Lawrence’s schooling was modest. Elementary school was capped by a two-year commercial course. His education was cut short by lack of scholastic aptitude more than lack of funds. A half century later, he revealed, “I was no boy wonder in education, it was always a struggle for me.” Throughout his life he would remain acutely conscious of his educational deficiencies. He invariably favored the highly educated, particularly Ivy League graduates, for his key appointments.

Learning the ropes

In 1903, the 14-year-old Lawrence apprenticed himself to attorney William J. Brennan. The association lasted for nearly 20 years, until Brennan’s death. Born into an Irish working class family much like Lawrence’s, Brennan began work at Jones & Laughlin Steel at age 11. He read law at night and established a practice in 1883. For Lawrence, the hours were long and the pay meager. In Brennan’s small office, legal practice and politics were closely intertwined. The non-academically inclined Lawrence chose politics over reading law; he read people. Brennan was a lawyer first and a politician second. This gave his young lieutenant the space to develop his political skills.

Today, after nearly 80 years of Democratic dominance in Pittsburgh politics, it is hard to imagine a time when Pittsburgh was held in the vise-like grip of a Republican machine. The nascent and weak Democratic organization was forced to cooperate within the space granted them by Republican bosses such as William Magee and William Flinn as they battled fellow Republicans Matthew Quay, Edward Bigelow, and others. Lawrence and Brennan worked slowly and patiently with the Republican overlords, exploiting their intra-party battles.Lawrence learned the art of compromise early, later reflecting, “We are practical people, not ideologists.”

No doubt to distance himself from his modest beginnings, Brennan adopted a formal style in dress and behavior. Lawrence mimicked his mentor. For Lawrence, coat, tie and white shirt with French cuffs became the order of the day. Even at home or at a picnic, informality was signaled by the occasional doffing of his suit coat, but the tie was ever present. As a professional politician, Lawrence cast his respect for political office in terms of dress appropriate to the office. When any of the Democratic faithful showed up at Democratic headquarters or Lawrence’s office in a short-sleeved shirt or no tie, they were admonished: “Goddamn it, you are a gentleman, this is an office.”

In 1912 Lawrence attend the Democratic National Convention accompanying Brennan as a page. There Lawrence met and bonded with a wealthy Westmoreland County Democrat, Joseph Guffey. Guffey—a future U.S. senator—went all out for Woodrow Wilson, whom he had known as a Princeton undergraduate. Wilson rewarded Guffey by naming him western Pennsylvania patronage chief. Guffey, in turn, appointed Lawrence minority commissioner for voter registration in Pittsburgh. The job paid $4,000 a year and was Lawrence’s first salaried political position.

In the absence of massive corruption on the scale of the Marcos regime in the Philippines, the life of the professional politician normally skates along on financially thin ice. In 1916 Lawrence launched an insurance agency with Republican State Senator Frank Harris. Lawrence knew little about insurance and was no businessman, but he made a great hire: Jimmy Kirk, who ran the Harris Lawrence Agency until his death in 1945. He was Lawrence’s closest confidant. In his later years, the agency provided Lawrence with an income of $15,000-$20,000 per year, and during his years out of office it provided the bulk of his income.

Standing 5’9” and full-bodied, Lawrence’s most distinguishing features were a large head, thick neck and broad shoulders. Early on, his mien and carriage marked him as a man of power. He possessed phenomenal stamina, working 12- to 15-hour days, often seven days a week. Like an athlete in training, he took care of himself. He neither drank nor smoked; he ate moderately and exercised regularly.

His mentor Brennan once told him that as a politician you could not “thrive and wive” at the same time. Only in 1922, after Brennan’s death, did Lawrence marry at age 32. Alyce Golden, the seventh child of Irish immigrants, was seven years younger than Lawrence. They had five surviving children, three boys and two girls. Lawrence was an absentee father and husband, and Alyce shouldered the full burden of raising the family.

Again, at the 1920 Democratic convention, a Guffey connection paid dividends for Lawrence. For services rendered, Guffey was named Democratic National Committeeman from Pennsylvania. He then appointed Lawrence to his old job as Allegheny County Democratic chairman. This was not a position of power, as the Democrats would remain in the political wilderness for another 12 years, until Franklin D. Roosevelt’s victory in 1932. Characteristically, Lawrence painstakingly put together a Democratic organization to fill the minority positions to which it was entitled. When the pendulum finally swung in his party’s direction, Lawrence’s nascent organization would propel Democratic candidates into office across the board, making him the most powerful Democrat in Pennsylvania.

The 1932 Democratic Convention was Lawrence’s most important yet, but he still played second fiddle to his powerful sponsor, Guffey. Lawrence’s heart was still with the 1928 candidate, New York’s Al Smith, but his head was with Governor Roosevelt. He was convinced that Smith’s Catholicism doomed his electoral prospects.

Going into the convention, FDR could count on only a few big city bosses, notably Ed Crump from Memphis, Tom Pendergast of Kansas City, and the Bronx’s Ed Flynn. Lawrence was not in their league, but in conjunction with Guffey he went all out for Roosevelt. They were able to deliver 55 votes on four ballots, more than those of any other state.

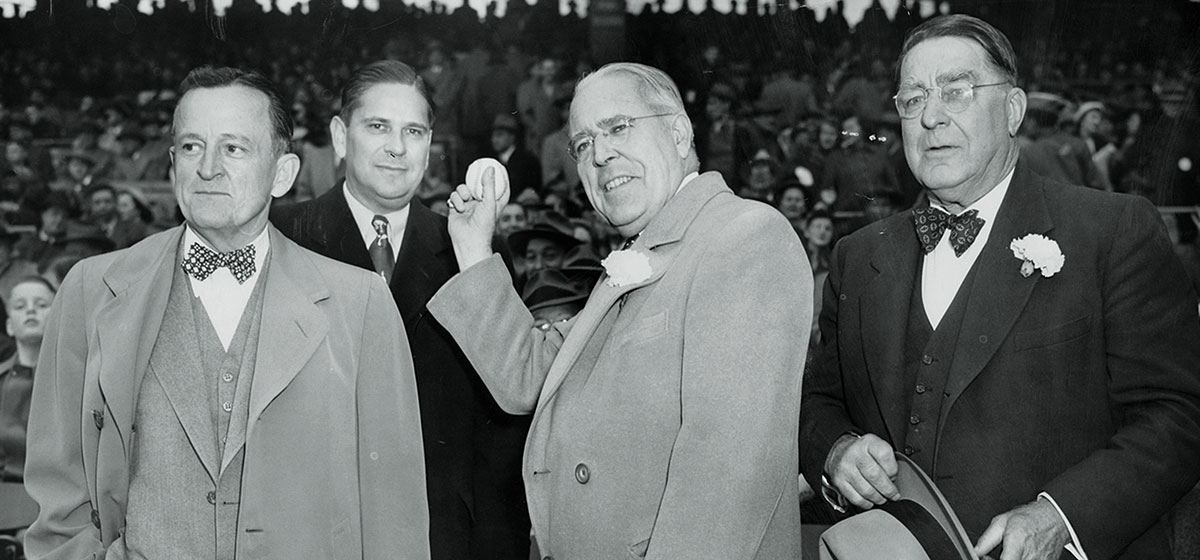

Lawrence then worked feverishly to bring both Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania into the Roosevelt column. With his firm grip on Pittsburgh’s 32 wards, he focused on ethnic minorities, including the Irish, Italians, Polish and other eastern and southern Europeans. His success with blacks was notable. Robert Vann, the editor of the nationally distributed black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier, was a long time Republican—as were most blacks since the Civil War—but he had gotten repeated short shrift from the dominant Republican machine. Lawrence secured an audience for Vann with FDR at his home in Hyde Park, N.Y. And the Roosevelt charm soon turned Vann, who brought home the bacon for the Democrats in Pittsburgh’s black wards and helped the ticket nationally. Lawrence then shored up his party’s finances by convincing some long-time Republican money men to shift to Roosevelt. Capping this fundraising effort was a $50,000 contribution from the great oil wildcatter, Mike Benedum. At Lawrence’s urging, FDR came to Pittsburgh. Lawrence gambled by leasing Forbes Field with 35,000 seats. Some 50,000 people crammed the ballpark. As a master stroke, Lawrence had Benedum introduce the candidate.

In 1932, Roosevelt failed to carry Pennsylvania. The shortfall was in Philadelphia. He won Pittsburgh by 27,000 votes and carried 27 out of 32 wards. FDR was prompt in rewarding Guffey, Lawrence and Vann. Guffey, the state’s top Democrat, received control of all federal patronage in Pennsylvania. He, in turn, delegated control in western Pennsylvania to his protégé.

Lawrence moved with dispatch to harvest the cornucopia of opportunities the Roosevelt victory presented. Putting aside calls to be the Democratic mayoral candidate in 1933, he chose Protestant blueblood William McNair. Lawrence ran the campaign, hammering home ad nauseum McNair as the Roosevelt candidate for Mayor and causing the New York Times to observe, “one might think that it was Mr. Roosevelt that is running for Mayor.” McNair won handily, but this was just the start.

In 1936, in addition to the mayor’s office, the Democrats controlled the County Board of Commissioners, held all nine seats on the City Council and most of the elected row offices. George H. Earle was elected governor and appointed Lawrence as Secretary of the Commonwealth, a dominant position in the state administration. With Guffey in the senate and conveniently out of Pennsylvania, Lawrence, who had been named Democratic state chairman in 1934, now held undisputed dominion over statewide Pennsylvania patronage. The fortunes of the Pennsylvania Democratic party would remain under his sway until his death in 1966. He was now “Boss Lawrence,” a position he long desired, but a moniker he thoroughly disliked.

The Lawrence machine

Former House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill famously declared, “all politics are local.” Nowhere was this more true that with the operations of the Lawrence machine in Pittsburgh. Even as he rose to regional, state and national prominence, his political power rested on a bedrock of local politics. Let’s go down into the engine room and see how the machine worked.

Pittsburgh, with a 1940 population of 676,000, was divided into 32 wards. The ward voters elected a committee, and its chairman was charged with maximizing the party’s votes on election day. The coin of the realm for the ward chairman was political patronage—jobs. In 1936, Lawrence as state Democratic chairman had nearly total control over 150,000 federal jobs, including 57,000 in western Pennsylvania. And in the depths of the Depression, a job was a dear thing. Once a ward chairman secured a job for one of his constituents, the new and thankful job holder was expected to secure votes from family, friends, neighbors and coworkers for the upcoming election. On top of the federal jobs were county and state jobs. They provided the dominant Democratic party with a powerful and virtually unbeatable arsenal in the election campaigns ahead. On election day, public employees were urged to be at the polls checking off the votes they pledged to deliver. They were expected to commit money in modest sums as well as their time.

The ward chairman was the point person for all Lawrence’s initiatives. Any job petitioner approaching Lawrence was politely but firmly directed to his appropriate ward. By 1936, this well-oiled system had 800 policemen and 1,000 firemen holding their jobs through the sufferance of their ward leadership.

Lawrence both derived and exercised his power through the ward chairmen. His relationship with the chairmen varied with their ability to deliver votes. Some highly successful chairmen ran virtually independent fiefdoms, while those with shortcomings felt Lawrence’s hot breath on their neck. When the chairman of a South Side ward was called on the carpet for his failure to deliver his quota of Democrats, he responded that it had rained all day. Lawrence replied: “How the hell do you think the weather was on the North Side?” Another chairman, when called on the carpet for producing a barely legible announcement, complained that his copy machine was not working properly. Lawrence cut loose with both barrels: “Don’t ever send me a thing like this again. Most of all you can’t read it, second it makes no sense. I’m near blind in one eye and I don’t want to lose the other.”

The formal structure of the party organization fit Lawrence’s proclivity for regularity and orderliness. Unlike Chicago’s Dailey, Lawrence seldom met individual citizens or small groups at City Hall. But in support of ward politics, Lawrence was ever visible at sporting events, weddings and funerals. More than once he said, “Visit the sick, bury the dead.” Charisma is not a word one would apply to Lawrence. He was well removed from the back-slapping style of Boston’s Michael Curley and New York’s Fiorello H. LaGuardia. Lawrence was at best a fair public speaker. An associate once observed you could always tell when Lawrence found a new word. He would beat it to death. One time it was “sanguine.” For the next few months he was invariably sanguine about this and not sanguine about that. Despite his natural reserve and “all business” personality, Lawrence won the hearts and minds of Pittsburghers. In a blue-collar town, he was the blue-collar leader. With his working-class background, despite his formal appearance and demeanor, he was always one of “them.”

Choosing the appropriate Democratic candidates for office was always a top priority for Lawrence. At “slating caucuses” in his Benedum Trees office, Lawrence spent countless hours working with Democratic party leaders to hammer out a winning slate. An acceptable candidate who could win was invariably chosen over an outstanding candidate whose vote-getting ability might be suspect. The party always came first, and the performance of the successful officeholder came second. Many times a solid vote-getter and an effective officeholder were one and the same. But all too often mediocrity triumphed at the polls; this was simply a fact of life with machine politics. One—build the party; two—win elections; three—dispense patronage, which in turn built the party. This was the three-cycle engine that powered the Lawrence machine.

The all-consuming nature of politics in general and Lawrence’s brand in particular showed in the way he administered his Pittsburgh fiefdom after assuming the duties of secretary of the commonwealth. He caught the 3 p.m. Friday train from Harrisburg, arriving in Pittsburgh after 8 p.m. On Saturdays, he was in his Benedum Trees office by 10 a.m. After two hours devoted to urgent business with his inner circle, he met the ward chairmen, reviewing the minutest details of ward politics. He seldom left before 6 p.m. On Sunday, he attended 10 a.m. mass at St. Mary’s at the Point. His duties as an usher permitted him to hold court in the back of the church. By noon, he would return to his office for a shortened reprise of Saturday’s schedule. On slow days he might summon his pinochle cronies for well-deserved relaxation.

The liberal legislation that Earle and Lawrence hoped to pass only became a reality after the sweeping Roosevelt victory in 1936. With Democrats firmly in control of both house of the legislature, they quickly passed the most liberal legislation the state had ever seen. It was called “the little New Deal.” Unfortunately for Lawrence, the honeymoon was to be short. From 1938 to 1944 he would wander in a political desert.

In and out of the desert

Troubles began with the 1938 state elections. Governor Earle could not succeed himself and ran for the senate. Lawrence selected Allegheny County solicitor Charles Alvin Jones. A Protestant, Jones was one of Lawrence’s weaker choices—he seemed convinced that Catholic candidates labored under a serious handicap. Guffey supported a rival candidate in the primary, adding to the growing breach with Lawrence. Both Jones and Earle, running for the senate, went down to defeat.

For Lawrence, political failure was coupled with the threat of jail time. In 1939, he was indicted and acquitted of taking kickbacks from an aggregates company. In 1940, he was forced to run the gauntlet again. This time, he was charged with threatening state employees to extract political contributions. Two years of constant litigation took their toll on Lawrence and his family.

The blame for the Guffey/Lawrence split is shared by both. Doubtless at its core was some jealousy on the part of the master for his student’s growing prominence. On Lawrence’s side, he violated his cardinal rule of compromise with his virulent attacks on Guffey in the 1940 Democratic senatorial primary. Guffey won and wanted Lawrence out as state chairman. Bowing to party pressure, Lawrence resigned, but secured the position of Democratic National Committeeman as part of the deal. This brought Lawrence into national prominence over the next two decades. At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1944, Lawrence was among a handful of Democratic powerbrokers who helped secure the nomination for Harry Truman. In addition to Lawrence’s other problems, tragedy struck in 1942, when his two oldest sons, David, Jr. and William Brennan Lawrence, were killed in an automobile accident.

Lawrence began his political comeback with the victory of his candidate, F. Clair Ross, over Guffey’s choice of Judge Ralph Smith in the 1942 Democratic mayoral primary. The victory over Guffey soon propelled Lawrence back into his old position of Democratic state chairman. Riding Roosevelt’s coattails, Lawrence led the Democratic slate to a clean sweep in 1944. Cornelius B. Scully, an Episcopalian, had been the mayor of Pittsburgh since 1936. Handpicked by Lawrence, Scully proved to be a competent mayor but barely eked out a victory in the 1941 Mayoralty elections. In 1945, the party was convinced they needed a replacement for the lackluster vote-getter.

The first choice of the party hierarchy was three-term County Commissioner John Kane. But Kane’s powerbase was in Allegheny County, not the city. He was reluctant to abandon it to play second fiddle to Lawrence. Instead he marshaled the leadership to promote a Lawrence candidacy. Arguing against his own draft, Lawrence listed three strikes against him: his highly publicized trials, the public’s innate distrust of professional politicians and his Catholicism. Finally, Lawrence acquiesced, and the formidable Kane agreed to be his campaign manager. Lawrence defeated Republican opponent Robert Wadell by a modest 14,000 votes. It was Lawrence’s first electoral victory in a 30-year career. In his subsequent campaigns, his election was never in doubt.

The Renaissance

In 1945, Pittsburgh was a rundown and tired city. Mayor-elect Lawrence faced a daunting host of problems. His old neighborhood in the Point was a tangled rabbit-warren of warehouses and railroad tracks. The last major office building erected was the 40-story Gulf Building in 1932; none was planned for the post-war period. Between 1900 and 1945, there were five floods, including the catastrophic flood of 1936, which left half of the commercial section of the city under 11 feet of water. Even worse was the smog caused by a combination of the belching steel mills and 142,000 homes heated by soft coal. On many mornings, the sky was dark by 9 a.m., and the city was ablaze with headlights and neon signs. Many of the city’s major corporations were making plans to move their headquarters to more accommodating environments. During his 13 years in the Mayor’s office (1946–1959), Lawrence was a guiding force in the transformation of the city in what was called the Pittsburgh Renaissance—a self-awarded title. The two principal thrusts of the Renaissance were cleaning the air and rebuilding a decaying downtown.

Lawrence was fortunate to have a dedicated business partner in Richard King Mellon, the son of R. B. Mellon and the grandson of Judge Mellon. R.K. Mellon, Chairman of Mellon National Bank, was the richest and most influential leader of the Pittsburgh business community. Neither Lawrence nor Mellon could have done it alone, but Lawrence was the first mover. His broad-brush plan for city revitalization found a receptive ear in Mellon. The vehicle that brought them together was the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, sponsored by Mellon in 1944. Far more so than today, Pittsburgh was a company town—the third largest headquarters city in the United States. Some 20 members of the executive committee of the Conference were the CEO’s of the city’s major corporations. Once agreed upon a course of action, when the Conference and General Mellon said “march,” the business community marched.

Within 24 hours of his election, Lawrence announced his campaign against air pollution. His statewide political power forced through the required air quality legislation while the conference beat back any recalcitrance on the part of the steel industry. Lawrence delegated more power to his executive secretary, John T. Robin, than any of his previous aides. Robin, in turn, worked with Mellon’s man, Arthur Van Buskirk, to keep the political and business teams in harness.

Until 1946, Mellon and Lawrence had not met. At Van Buskirk’s urging, Mellon made the brief walk across Grant Street to the mayor’s office. For Lawrence, who had battled Mellon’s older cousin, W. L. Mellon, for years, the meeting doubtless had a surreal quality. The dynamic Lawrence and the laid-back Mellon were opposites in personality as well as background. This odd couple never became friends, but their shared love of their native city created a force that drove all else before it.

During the ’30s, there had been plans to create a park at the Point and surround it with much-needed office space. The project languished until March 9, 1946, when a spectacular fire provided the catalyst to create Point State Park and Gateway Center. The public/private instrument for urban renewal was the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh (URA), which held its first meeting that November. Lawrence intended to appoint Van Buskirk, the chairman of the Allegheny Conference, as head of the URA. Van Buskirk, however, had a better idea: Lawrence as chairman. At first reluctant, the mayor agreed on the condition that Van Buskirk serve as vice chair along with two other conference members.

The Equitable Life Assurance Company of America developed the Gateway project, which began with three 24-story office towers bordering Point State Park. Negotiations took four years, with construction beginning in 1950. Seven major corporations moved their headquarters into the new space. The URA purchased the Jones & Laughlin Steel building, permitting the company to move to Gateway. This was one of numerous URA initiatives under Lawrence’s guiding hand which made the vision of the urban planners a reality. The Mellon Square project followed shortly thereafter. During a 15-year period, the Pittsburgh Renaissance transformed over 1,000 acres in 16 projects. Over $622 million went into these initiatives, including $500 million of private investment.

The Pittsburgh Renaissance was, in part, greased by steady corruption, occasionally punctuated by headline-grabbing scandal. Ground Zero for this corruption was the police department. Lawrence tacitly supported what he might have termed “low level corruption.” He opposed a state law placing detectives and inspectors under civil service control. All-night bars, gambling establishments and the numbers rackets flourished throughout the Lawrence years. The best example of his indulgence of criminal activity was his steadfast refusal, despite badgering by several members of his executive staff, to fire police superintendent Harvey Scott, who had held the job since 1939. When the heat from the press became unbearable, he called Scott and his senior officers in and read them the riot act; nothing changed. Finally Scott was hoisted by his own petard. Within a two-month period in 1952, Scott appeared intoxicated at a grand jury hearing and engaged in a brawl at a restaurant. Having no choice, Lawrence replaced him with an energetic, young Jim Slusser, who made marked progress in reducing police corruption.

But even the hard-driving Slusser had to work against political headwinds. The day after his appointment, a man walked into his office and announced he was Slusser’s new inspector. Slusser threw him out and within hours Lawrence called and informed him that the man had received his appointment through his ward chairman, and ordered him reinstated. These actions and others were indelibly stamped on Lawrence’s 40-year behavior pattern. His ability to get things done, most specifically his herculean efforts on behalf of the Pittsburgh Renaissance, rested on the grassroots support he enjoyed in the wards. A corruption-free police force simply did not fit into Lawrence’s modus operandi.

A nominal capstone to Lawrence’s political career was his 1957 election as governor. It was a position he neither desired nor sought. His great work over 13 years in Pittsburgh and his prominence on the national level overshadowed his four years (1959–1963) in Harrisburg. Lawrence’s strong desire was to finish his final term as Pittsburgh mayor. But when Democratic Governor George Leader found himself at cross purposes with the powers in Philadelphia, Lawrence was the only man left standing. He narrowly defeated the pretzel king from Reading, Arthur T. McGonigle. Three weeks before the end of his term, President Kennedy offered Lawrence a job as chairman of the President’s Committee on Equal Opportunity in Housing. It was a subject in which he had a keen interest and offered a new challenge in a new environment. He accepted, and served in that capacity under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson until his death in 1966.

While Lawrence spent considerable time in Pittsburgh—he still chaired the URA—the Lawrence machine was no longer firing on all cylinders. Bearing witness to this was the defeat of the organization candidate Bob Casey by the wealthy Philadelphia electronics manufacturer Milton Shapp. The Independent Shapp was smart enough to know that he needed Lawrence and the party organization. He sought rapprochement and Lawrence accommodated him.

On Friday evening, November 4, 1966, Lawrence spoke on behalf of Shapp at the Syria Mosque in Oakland. While at the lectern, the 77-year-old Lawrence was felled by a heart attack. He lingered on at Presbyterian University Hospital for 17 days, but never recovered consciousness. Only a month earlier, he had told Press writer Kap Monahan, “Don’t retire—don’t think of it. Keep on at your work and when your time comes, why not die in harness.” He did just that.

How did David Lawrence accomplish so much? He was a professional at the highest level. He was not an intellectual. He was not an ideologue. He was an “action man” who got the job done. At the heart of his profession was selecting people. Different rules applied to specific categories. Rank and file workers were selected through the normal patronage process. Candidates for office were chosen on their vote-getting capacity. Ability and training were of secondary importance. Top administrative appointments were chosen by education, experience and ability. Categories one and two were the foundation upon which category three rested.

Lawrence was an outstanding leader. His commitment of both time and intensity was nearly total. His meetings, seldom lasting more than 15 minutes, were sharp and to the point. Invariably, they concluded with a clap of his hands or a bang of his large ring on the desk. There was never a joke to lighten the mood. On a scale of one to 10, his sense of humor was just south of one. He was punctual to a fault. Running for governor in 1957, his running mate John Davis was habitually late. Once appearing on the same platform with Davis, Lawrence cooled his heels for 15 minutes. When called out on his tardiness, Davis replied, “I’m only 15 minutes late.” Lawrence blasted back: “You are 15 minutes too goddamn late” and walked off the platform.

An aide once described Lawrence as “a nice Lyndon Johnson.” This is hardly high praise, but there are similarities. His legacy is all around us today in America’s most livable city.