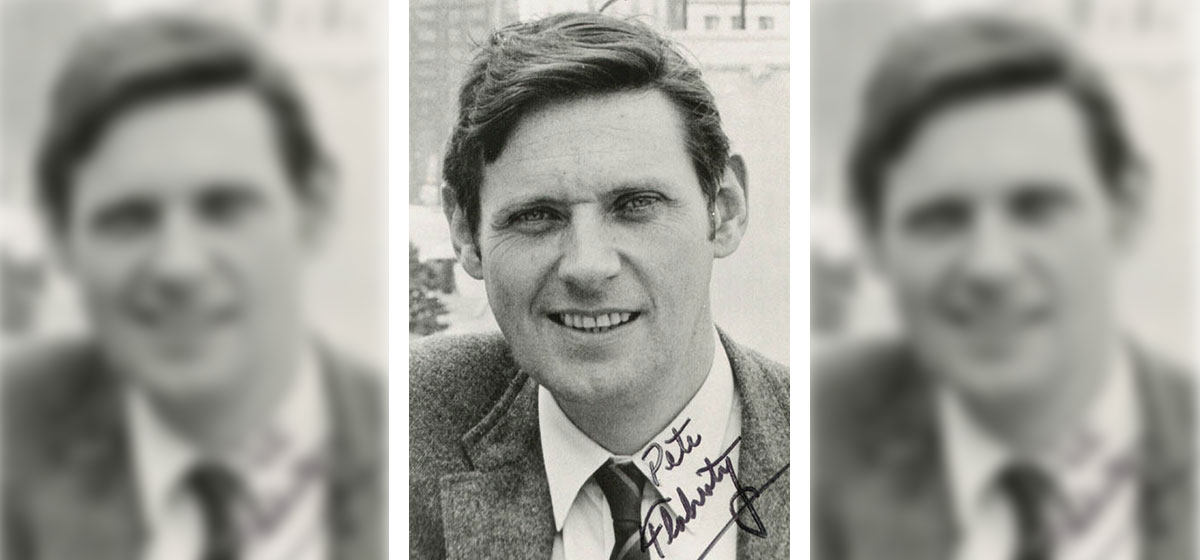

Considering the Record of Mayor Pete Flaherty

As Pittsburgh prepares to elect a new Mayor and embark on all that a new administration represents, it may be worthwhile to consider the tenure of another Democrat mayor who held the office 50 years ago.

On January 5, 1970, Democrat Peter F. Flaherty was sworn in as mayor of Pittsburgh and, as promised, focused on the neighborhoods and fiscal responsibility. He had an excellent background having served as an assistant district attorney, run for City Council in 1966 and led the Democratic ticket, and while a Member of City Council earned a master’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School for Public and International Affairs (GSPIA).

I moved to Pittsburgh in 1965 to join the law department of US Steel. When Pete Flaherty ran for mayor, his campaign captured my attention. When an article appeared in the paper stating he was interviewing those who were interested in serving for his administration, I applied and was hired as director of lands and buildings. In September of 1970 I was promoted to executive secretary which in effect was the mayor’s chief of staff. I served in that capacity through Flaherty’s terms as mayor.

During his tenure, real estate taxes went down. This was achieved through new technologies and efficient management, including reducing the jobs budgeted from 7,000 to 5,000. Coal-fired heating at City Hall was replaced by gas or steam heat; this was also done in the Phipps Conservatory, fire stations and local zoo. Direct dial phones replaced ’round-the-clock telephone operators, the first computers were used, and Forbes and Fifth avenues were made one-way. Skating rinks and night lighting for tennis courts were added. The Baum Boulevard Bridge was rebuilt. Pete also improved garbage collection and street lighting and dramatically increased the number of roads paved and cement-lined water mains. Complaints about refuse collection declined by over 25 percent from the first six months of 1971 to the first six months of 1975. The City’s fire services as rated by the American Insurance in 1975 were better than any time over the prior 25 years. As of 1975, measured by FBI statistics, Pittsburgh was the only city of almost 50 cities where the crime rate had not increased over the prior six and a half years. The crime rate decreased from 32,113 crimes in 1969 to 29,253 in 1974.

Pete made land available for building the Scaife Gallery, renovating Heinz Hall, and expanding Duquesne University and the University of Pittsburgh while helping to preserve the Forbes Field wall over which Bill Mazeroski hit his World Series-winning home run in 1960. Pete was very supportive of the Station Square development and his Urban Redevelopment Authority Executive Director Steve George and Bob Lurcott Director of City Planning, both architects, helped Pittsburgh Plate Glass in the planning of PPG Place.

Pete was a pioneer in affirmative action. He hired Chuck Cooper the first Black hired in the NBA and Louise Brown to work in the mayor’s office and then promoted director of lands and buildings. Harold West, a Black man, succeeded Steve George as director of city planning in that position. His Deputy Planning Director Billie Bramhall was the first female in the United States to achieve the position of director or deputy director of city planning in any city. Several Blacks were promoted to the rank of inspector in the police department, the highest-ranking supervisor under the rank of chief and assistant chief. A woman, Mildred Sladic, was made an inspector because of the fine quality of her work managing the school crossing guards. She supervised many more personnel that any other inspector. For several years, the mayor followed a court order he deliberately did not appeal which required hiring one Black male, one Black female, one white female and one white male for the filling of police and fire department vacancies. The order was reversed under a future mayor. Pete Flaherty adopted one of the first affirmative action programs in the State of Pennsylvania.

Two significant accomplishments under the Flaherty administration are usually overlooked and misconstrued.

The first was the omission of the fact that the Flaherty administration shifted from politics to labor relations in dealing with the employee representatives as required by two new laws that gave all employees below supervisor the right to bargain a labor agreement to define the employees’ rights and the City’s obligations. Under the prior administration, politics determined the relationship between the City of Pittsburgh and those employees who belonged to unions, including police and firefighters. Pennsylvania Act 111 of 1968 gave police and firefighters the right to bargain collectively and the right to have their contracts determined in binding arbitration by an impartial arbitrator selected from list of three provided by the State Labor Board. In the summer of 1970, Pennsylvania became one of the first two states to provide collective bargaining and the right to strike to public employees. These laws dramatically changed the way union eligible employees were paid wages and benefits by making it so that these matters were negotiated into a labor contract with a handful of unions instead of having all the unions negotiate separately with the mayor’s office to achieve success for their union. Ultimately, drawing on my background with US Steel, I negotiated all of the collective bargaining agreements with the city employees, including the police and fire contract.

As Mayor, Pete Flaherty’s administration during its term negotiated the first collective bargaining agreements with the Police and Fire Unions pursuant to Act 111 of 1968 and went through the union certification process for the unions under Act 195 of 1970 without any significant difficulty and negotiated the first collective bargaining agreements with the Act 195 units again without any difficulty. Over the seven years that Flaherty was in office, fewer than eight grievances went to arbitration all from the Act 195 units. The City of Pittsburgh prevailed on all grievances.

Despite Flaherty’s success in dealing with the issues of certification of the unions, collective bargaining and grievance arbitration the media tended to characterize him as anti-union. This may have been based on a strike of all blue-collar employees led by Teamsters 249 of which the President of Council was the leader. This strike occurred in an effort by the Teamsters to preserve truck driver jobs for teamsters to drive plumbers in pickup trucks to install water meters because Flaherty had laid off the drivers. They were laid off because no other city in Pennsylvania used teamsters to chauffeur plumbers to install water meters, and in the other department of the City of Pittsburgh that employed plumbers, the plumbers were not chauffeured.

The strike ended because a court action was initiated by a non-profit agency that resulted in a decision that the strike should be enjoined because the strikers were in violation of the new Act 195 of 1970 that required the Labor Board to certify a union for collective bargaining before there could be a strike. Since no union had been certified or even attempted to be certified, the strike was enjoined. The plumbers then drove the pick-trucks because the mayor had said that if they did not, the meter installation would be contracted out.

That was also the end of the Teamsters’ power with the City of Pittsburgh. It was the beginning of proper procedures being implemented by the unions to comply with Act 195 of 1970, to start bargaining between the City of Pittsburgh and those employees represented by a Union that was elected by them later in the year for an appropriate unit certified by the Pennsylvania labor Relations Board. By ignoring the impact of Act 111 or 1968 and Act 195 of 1970 the media and historians have omitted a critical history of labor relations in the City and the change from political labor relations to labor relations following the labor laws of Pennsylvania.

The second was really a very significant accomplishment of John P. “Jack” Robin, who was probably the most effective administrator during the real Renaissance under Mayor Lawrence in Pittsburgh. Robin went away from the area in the 1960s and returned in 1973. Within two years, he had been appointed to the Board of Port Authority and had learned in December 1974 that the Federal government was saying that it would not provide finds being held for Pittsburgh transit if there was not a decision on the renovation of the transit system in Pittsburgh. A Westinghouse Electric Skybus transit system had been tested in South Park starting in 1967. It was driverless and ran on an elevated concrete track. Westinghouse Air Brake WABCO proposed an alternative transit system in 1969 and there followed several years of controversy surrounding Skybus and the WABCO proposal that one of the County Commissioners and Mayor Flaherty both opposed, and Governor Shapp ultimately opposed.

As a result, Robin called for all parties involved to appoint representatives to address the issue so that a positive response could be sent to the Federal government. The result was that Port Authority, the three Commissioners, the Mayor, the Governor, City Council, and Labor all appointed a representative and this group met two times within 10 days. The Mayor and Governor proposed an alternative system that had many more stops in the city, a larger transit vehicle, an underground stop downtown and that was much less expensive than Skybus. The task force, as it was called, agreed unanimously that a consultant should be selected to evaluate the transit proposals made, including one by the Mayor and Governor together, that the scope of the study should be determined by the City Planning Director Bob Paternoster with John Mauro, executive director of Port Authority who had been planning director under the Mayor immediately prior to Flaherty. At the second meeting the consultant, DeLeuw Cather and Company was agreed upon unanimously.

A year later, DeLeuw Cather issued a 700-page report evaluating the four transit proposals submitted. The report ranked the proposal submitted by the Mayor with Governor Shapp number one and ranked Skybus fourth.

The recommendation was unanimously approved by all parties and the Federal government and that was the end of Skybus for Pittsburgh.

The key point is that transit was one of the biggest issues in the history of Pittsburgh, but the unanimous solution suggested and supervised by Jack Robin was probably the easiest and the most effective achieved on any major issue in Pittsburgh’s history. This should have resolved the controversy for Pittsburgh transit, but there are those who ignore or downplay the enormity of the solution that brought Skybus to an end for Pittsburgh. They blame Mayor Flaherty for a claimed great loss that is not supported by the DeLeuw Cather independent report that was supported and implemented by all interested parties, including the Federal government.

The DeLeuw Cather report was received in the spring of 1976. By the end of 1976, Pete Flaherty had accepted the position of Deputy Attorney General of the United States from President elect Jimmy Carter. Flaherty asked me to join him as associate attorney general of the United States and I accepted and left the City in March of 1977.

Flaherty left a budget surplus, no new tax increases, and a number of administrators who continued into the next administration, including Chief of Police Bob Coll, Director of City Planning Bob Lurcott, Parks Director Louise Brown, Director of Personnel and Civil Service Melanie Smith, Budget Director Ken Fields and Executive Director of the Urban Redevelopment Authority Steve George.