Compassion, Mindfulness and Resilience

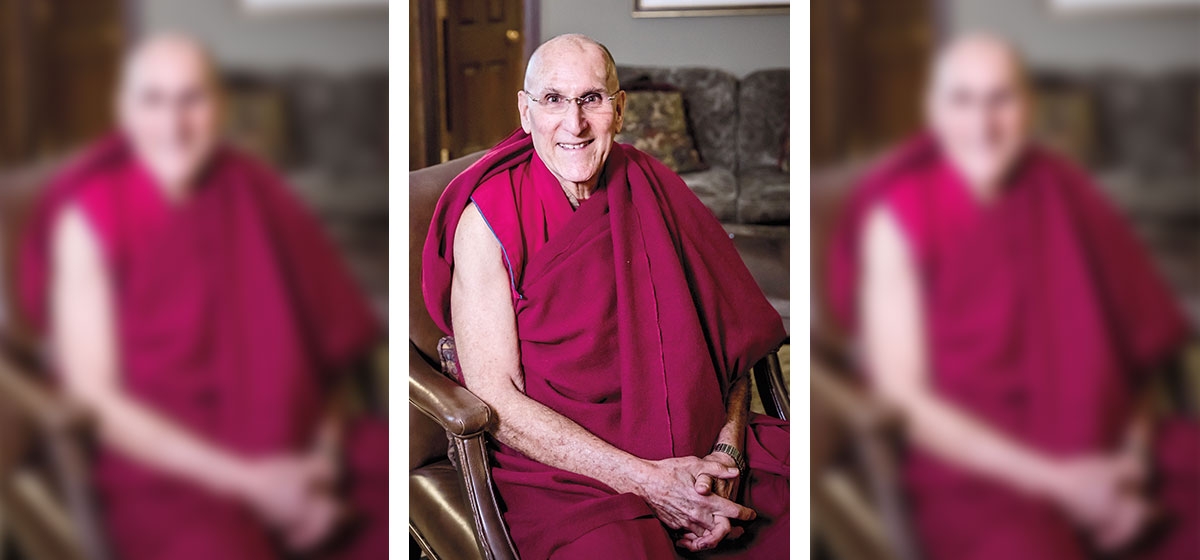

A native of California, Dr. Barry Kerzin is a Buddhist monk and the physician to the Dalai Lama. He sat down with Pittsburgh Quarterly to discuss his recent visit to Pittsburgh.

Q. You’re here to work with many of UPMC’s 16,000 nurses for training in compassion, mindfulness and resilience. How do you do this?

A. The approach is two-pronged. No. 1 is the indirect approach—to recognize and then transform the barriers. The premise is that our default state when we’re born is compassion. There’s some really good research out of the University of Wisconsin in which they looked at 4-month-olds, put them in front of a little screen and showed them some animation of a similar infant trying to roll a ball uphill. In one animation, there’s a second child helping, and they observe the real child watching. And the real child moves toward the screen, smiling and being active. They do a second experiment that’s the same except that the second child in the video is trying to push the ball down the hill. And the real infants move back and furrow their brows. It’s still an open question, but this research suggests that compassion is our default setting, and we operate under that approach.

So what are the obstacles? Anger, jealousy, and pride. Anger you can recognize. Pride, arrogance and jealousy, we may or may not recognize. That’s where mindfulness comes in. It allows us to look inside at the present moment. What are we thinking? What are we feeling? And when we notice and recognize those destructive emotions—anger, jealousy and pride—then we have an opportunity to work on them and to learn approaches so we don’t suppress them, because that doesn’t help. We want to actually transform them to their opposites—anger into tolerance, jealousy into appreciation, and pride into humility.

For the direct approach, there are a number of things people can do. Increase their giving. That could be money, but it doesn’t have to be. It could be a smile, opening a door, or non-judgmental listening to a friend who’s having some difficulty. Second is trying to develop an approach in our life of no harm—not harming others and not harming ourselves. Being more gentle and loving to ourselves and others, in our words, but also in our mind, thoughts and feelings. Trying to move slowly in that direction of no harm. Third is developing tolerance, patience and understanding instead of getting angry. And fourth is to focus our minds. Our minds tend to bounce all over the place. And when do that, we don’t have the power in our mind, the momentum to really get things done well and thoroughly.

Q. I assume most people are not very focused. What would be an example of someone who’s not focused?

A. An example is being on the phone, holding it in your shoulder with your hands on the computer. And then talking to someone else—a kid—all at the same time. You’re not getting anything done very well because you’re not focused on one task. As we meditate regularly, focusing on our breath, slowly what happens is that the clutter in our mind reduces. Then we have a lot more room for perspective; we can see more and make better decisions.

Q. So the idea is that if nurses and doctors walk down this path, it’s helpful to them and to their patients?

A. And also their family members. But primarily we’re doing it for them so they can be happier and healthier, but it transfers to all of their relationships including their patients. So there’s more trust that’s developed with their patients—and that’s an essential ingredient in healing.

Q. Why is trust an essential ingredient in healing?

A. There’s been some research that people heal better when there’s a trusting relationship with their provider. For instance, if we’re skeptical of the doctor or the process, we might be less likely to take the medication. Second is satisfaction. If you have a trusting relationship, you’re going to walk out of the office more satisfied, and that has a relationship to healing. And there are other things we don’t fully know. One is epigenetics—it’s all about turning on or off the genes. Traditionally it was thought that the micro environment—temperature, pH, and pressure for example—were the controlling factors of which genes are being turned on or off. But now they’re finding that positive emotions are a factor, and that’s where trust plays a role, as do meditation and compassion. Emotions seem to have a positive effect on producing healthy protein for the immune system. It’s complicated, but there’s some good early research.

Q. Is it fair to assume that, conversely, negative thoughts have a depressing effect?

A. We know that. In medicine, we talk about Type A personalities—people who are angry a lot of the time. We know they have more heart disease and die earlier.

Q. Regarding the mind-body connection: In medicine, how important generally is one’s outlook?

A. There’s a strong connection between your mind and body. Traditionally medicine hasn’t recognized that, but that’s changing. So many of our major illnesses have stress as a factor—maybe not as causation, but sometimes as causation. Probably more as an important factor in driving chronic illness—blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, emphysema. And stress has so much to do with the mind. It’s my belief that the mind is stronger than words and words are stronger than physical actions.

Everything kind of comes from the mind. And that means our motivation. Usually we’re not in touch with our motivation. And often our motivation is mixed. But the more we can turn inward—this mindfulness stuff—and know what we’re thinking in the present moment, the more we can begin to be in touch with our motivation. And of course motivation is going to change. But when we get in touch with it, and find that it’s more selfish, those people who are interested in finding greater peace and happiness can say, “OK, if I really want to help others without these strings attached, then I have to move myself in this direction.” But first I have to recognize my motivation.

When I was a medical student, I had an incredible professor, my mentor. Once we went out to visit nearly a dozen women who had lupus to see if they had had some major stress in their lives in the 18-month period before their diagnosis with lupus. Nearly everyone had. It was an eye-opener to see the effect stress has on major illness. We know that emotions and thoughts are connected to the brain. And the brain is connected to the peripheral nervous system, which drives a lot of organs in the body.

Q. How often do you meditate?

A. Every day

.

Q. Are there certain times of the day? Is it variable?

A. No, it’s pretty regular. I meditate every morning for about an hour and a half, sometimes two hours. And in the evening for half an hour, sometimes an hour. Depending on what I’m doing, I don’t miss a day.

Q. As a doctor and a spiritual person, if you had to choose, which would you say is more important—meditation or aerobic exercise?

A. I would probably say meditation. But having said that, I really like aerobic exercise and feel it helps me a lot. I say meditation because if you do it regularly every day, after some time—maybe months or a couple years—you’ll start feeling happier inside. And that’s something you can’t buy. Of course aerobic exercise brings tremendous benefits, but I think they go deeper and are more long-lasting with meditation.

Q. If you were suggesting to someone who’s not versed in meditation how they would begin, what would you suggest? How would someone who’s reading this story say “OK, I should try that. How do I go about it?”

A. Meditation is a mental training and it’s analogous to training the body. If one is an athlete—not just a pro—you’ve got to train, several days a week, almost every day to stay in shape. It’s the same with the mind. You have to have a regularity. Otherwise, you kind of lose it.

First, do it regularly. Maybe even every day. Second, if you do it for a long time, you’re not going to continue, because it’s just too rigorous. So just do it for five minutes. And it’s a good thing to do it in the morning, when you’re more fresh (unless you have a night shift). And try to find a place in your living quarters that you designate as your place to do meditation. Now, it depends how limber and flexible your body is. Some people who do yoga can easily sit on a mat with maybe a two-inch rise underneath their bum—that’ll straighten your spine and make it a little easier to sit. If that’s less comfortable, sitting in a chair is perfectly fine.

I recommend doing a meditation on the breath where we actually focus the attention on the base of the nose, the upper lip. We keep our eyes open, glancing down maybe a yard in front of you. With a soft gaze, so you’re not staring at the carpet in front of you. The reason for open eyes is that, with time, the mind will be more clear, and that’s said by great teachers. When the mind gets distracted, which is most likely going to happen, try to bring your mind right back and place your attention to the base of your nose. That coming back is the mental training to counter distraction. Please don’t expect much, because most of us have monkey mind, where the mind is jumping around a lot. We’ve been doing that for a long time—decades depending on how old we are—so to expect to counter that immediately is unrealistic. That’s why we have to keep training. But if we stay with it, slowly we’ll find that our mind becomes more concentrated; we’ll become more peaceful inside. There are many other types of meditation and study, but this is a good place to start.

Q. How did you learn these lessons?

A. Trial and error, teachers, interest, enthusiasm. When I was 17, I bought a poster that said meditation on it—it had a picture of an old guy—and I put it up on my wall. I was a little bit attracted to mediation. I didn’t know why. I first got involved in the Hindu tradition with a friend who was a neighbor. And then I’ve had wonderful teachers over the decades. His holiness the Dalai Lama has been a close teacher.

I’ve made lots of mistakes. It’s like anything else. You try it and if it doesn’t work, you make adjustments. And that’s OK.

Q. How would you compare the two great goals of peace and happiness?

A. For me, they’re pretty similar. The distinction here has to be made between a superficial level and a deeper level. You can call it peace or you can call it happiness. On a superficial level, it’s based on our senses. You get excited by the lovely taste of food, watching a lovely film, beautiful scenery in nature, or hearing beautiful music or the sounds of nature. Or tactile human contact—sexuality. All of these are sensory based, and I call them pleasure. They don’t last. They last for some time and then they finish. And sometimes they even turn into their opposite. You lay out on a beach and you fall asleep and you wake up and you’ve got a sunburn. Go to an all-you-can-eat place and you get indigestion.

On a deeper level it’s not related to the senses, it’s the mind that cultivates some of these qualities—of humility, of appreciation, of tolerance, of giving, etc. The more we do these things, the more we have a sense of meaning and satisfaction. And that then brings this deeper level of peace or happiness that’s not related to sensory experience.

Q. I presume you would say that, in one’s travels through this world, the goal of living is to make that transition to more of that latter sense you described.

A. I think that’s true. But we need a caveat. It doesn’t mean that we just hide away or escape from society and spend our life alone. I think it’s the opposite. The goal is to be more actively engaged in society—to be more actively concerned and fighting injustice. And to do what we can. So when we fight injustice and hate, which is becoming more prevalent in this country and around the world, we have to be tough. But we don’t do it out of anger. Inside we’re peaceful. Some people don’t get that. Some people think compassion is limp and passive. Actually it’s the opposite. Dr. Martin Luther King was incredibly powerful and strong, but he was motivated by love not anger. Mother Teresa was incredibly strong and active, but it was out of love and compassion, not anger.

Q. Many of us around here are working to create a better city. And growth is often seen as the goal. We are a place that, because of a demographic anomaly, doesn’t have population growth, which is the easy way to get economic growth. Would you agree that building a better city is a matter of growth, and if so, how?

A. I would agree that growth is the measure. But the question is what kind of growth. And I would suggest growth in the meaning of people’s lives. And this is not a pipe dream. Greg Fisher is the mayor of Louisville and a friend of mine and also a friend of your Mayor Peduto. He’s working on creating a compassionate city. They have a compassionate schools program and are moving into other areas. And your mayor is interested in this. I hope more of this will be rolled out in Pittsburgh and we’ll be talking with Mayor Peduto about this. He’s asked me to meet with law enforcement officials here.