Central Bankers Then and Now

Not that anyone cares, but in these pages I’ve been highly critical of the “unconventional” policies pursued by every central banker on the planet since the Financial Crisis.

My arguments have been many and simple:

The policies not only didn’t work, they actually stunted economic growth.

The policies were “immoral” in the sense that they rewarded the worst behaviors (greed, dishonesty) during and prior to the crisis and punished the best behaviors (saving money, playing by the rules).

The policies evidenced nothing so much as central banker groupthink.

The policies massively interfered with the efficient and effective allocation of capital throughout the US and the world.

By mispricing money, central banker policies created a “lost decade” of tepid economic growth.

The central bankers did accomplish one remarkable feat: they so infuriated ordinary people that populism has returned with a vengeance.

When I debated Ben Bernanke about quantitative easing a couple of years ago, whenever he got cornered and couldn’t think of a way out, he retreated to what I think of as The Last Refuge of the Central Banker Scoundrels: “We prevented another Great Depression! Things could have been much worse!”

That argument is intended to halt discussion, but what it really halts is thought. The subtext is that in the 1930s central bankers and government policymakers were stupid and did all the wrong things, while today they are brilliant and saved our bacon.

But is it true? Let’s go back and take a look at the Great Depression and the policies that were pursued back then, and we’ll compare them to the Great Recession and the policies that were pursued now. And then we’ll compare the outcomes of those policies.

The depression that we think of as the “Great Depression” happened so long ago—90 years—that it has entered the realm of legend. If you ask any random person about it they will tell you that the Depression began with the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and didn’t end until the US entered World War II.

That’s not precisely wrong, but it’s badly misleading. And since we are talking about something important for our future—appropriate monetary and fiscal policies for economic booms, recessions and depressions—it’s important to get the facts right.

What we think of as the Great Depression was actually a series of partly related phenomena, namely: a huge economic boom (1920s); the unwinding of that boom by a market crash and deep recession (1930-32); a flat year as the economy righted itself (1933); a powerful recovery (1934-37); a brief, shallow recession (1938); another powerful recovery (1939-40).

Here is the actual GDP data from the Depression period, along with my gloss:

Year and Growth/Decline:

- 1920s……………………………… +42% (over-the-top boom, bound to end badly)

- 1930……………………………….. -8.5% (it ended badly)

- 1931……………………………….. -6.4% (really badly)

- 1932……………………………….. -12.9% (what the #!@%?)

- 1933……………………………….. -1.3% (the economy rights itself, finally)

- 1934……………………………….. +10.8% (powerful recovery, but from a low base)

- 1935……………………………….. +8.9% (now a serious recovery)

- 1936……………………………….. +12.9% (zowie, US GDP now above 1929 level)

- 1937……………………………….. +5.1% (still going strong)

- 1938……………………………….. -3.3% (oops, Roosevelt raises taxes)

- 1939……………………………….. +8.0% (another strong recovery)

- 1940……………………………….. +8.8% (still booming)

In short, since the ’29 Crash, GDP had 3 down years, 1 flat year, 6 up years.

In the boom times of the 1920s, a lot of people did a lot of dumb things. They paid way too much for way too many stocks. They bought those stocks on margin. They borrowed too much money against their businesses and farms, forgetting to consider how they might pay it back if the boom ended.

Naturally, the boom did end, as all booms do, and a lot of people got badly hurt. People really did jump out of their office windows shouting, “Ruined!” There were breadlines and Hoovervilles.

But we need to keep a perspective on the Crash of 1929. At that time very few Americans owned any stock at all, and the percentage of people who owned enough stocks to be bothered by the price collapse was infinitesimally small.

Yet, the Crash was followed by a long and deep recession. Why?

We could side with the Keynesians and believe that the recession was caused by a plunge in aggregate demand. Or we could side with the monetarists and believe that the recession was caused by a sharp contraction in the nation’s money supply. Or we could side with Your Humble Blogger and believe that both explanations are right.

Unhappily, in the early twentieth century Americans were used to recessions because they had been happening ever since the dawn of history. The late nineteenth century had been especially prone to crises, as was the early twentieth century.

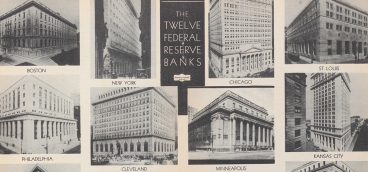

Indeed, it was the Panic of 1907 (when stocks fell 50% in three weeks) that led to the formation of the Federal Reserve System and the invention of American central bankers, who were supposed to prevent this sort of thing. There were so many difficult economic periods that the recession of 1930-33 was only the sixth worst in US history up to that point.

Many people, especially modern central bankers, argue that if, immediately after the Crash of ’29, central bankers had been more accommodative (lowering interest rates, pumping money into the economy), and if the US government—the Hoover and Roosevelt Administrations—had pursued stimulative policies (deficit spending, tax cuts), the recession that began in 1930 might have been far less deep and prolonged.

Frankly, I doubt it. The long boom of the 1920s had to unwind, and in 1930 it unwound so powerfully that there was probably very little anybody could have done about it. The error lay in not reining in the economy during the boom. Still, monetary accommodation and fiscal stimulus certainly don’t hurt when the economy is falling apart. The key question, though, is one of scale: how much is too little and how much is too much?

I agree that in the 1930s the Fed erred on the side of “too little.” But I also contend that, following the recent Financial Crisis, the Fed erred on the side of “too much.” And I will also argue that, if we had to choose, we might side with the “stupid” central bankers of the 1930s.