Brothers & Keepers?

Editor’s note: Between 1984 and 2019, attorney Mark Schwartz represented convicted felon Robert Wideman, ultimately securing a commutation of his sentence in 2019. This is his account of what transpired in the 35 years he dealt with Wideman and his famous older brother, the author of “Brothers and Keepers.”

Over the past 40 years, I’ve built a legal practice that has focused mainly on civil rights cases, whistle-blower cases and plaintiff’s cases of all kinds, but mainly representing minorities and people of color. My career’s bucket list case was finally won with Robert Wideman’s commutation in the summer of 2019. I only have admiration for him and his life’s progression. However, when it comes to his brother, noted author John Edgar Wideman, my feelings are different.

Starting back in 1963 with Gene Shalit’s Look Magazine article “The Astonishing John Wideman,” and as recently as a 2017 New York Times Sunday Magazine cover story “John Edgar Wideman Against the World,” Robert Wideman’s 10-years older brother has been touted by the national media as being nothing less than the great hope from Pittsburgh’s inner city.

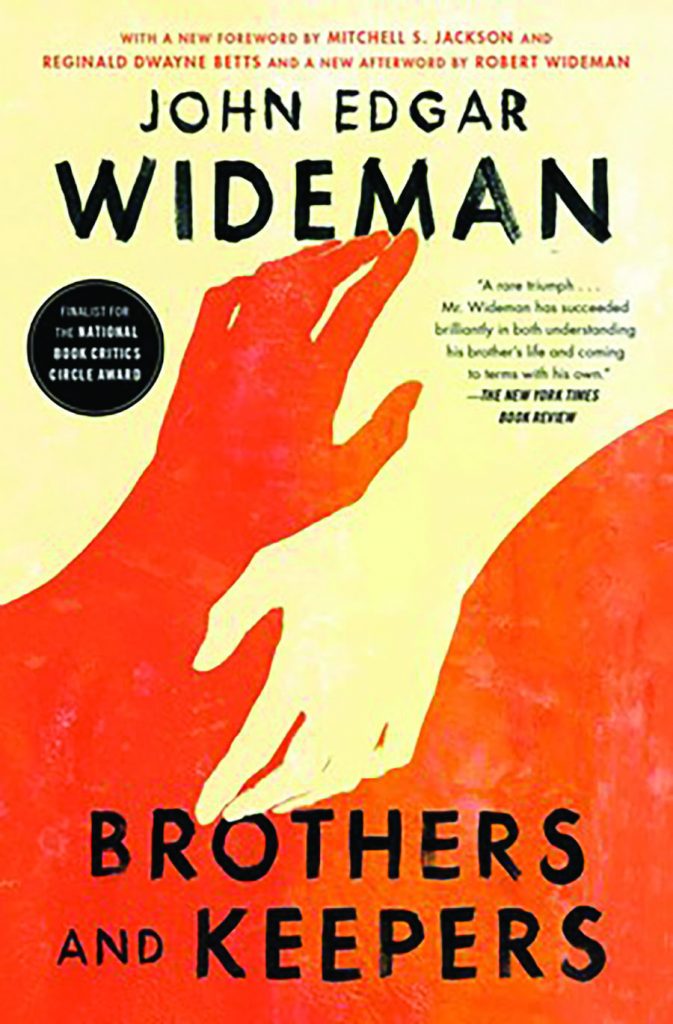

John first gained critical praise for authoring his “Homewood Trilogy,” a series of family vignettes passed on to him by his grandmother. This was followed by the 1984 publication of “Brothers and Keepers,” a memoir concerning his relationship, or lack thereof, with Robert, who became my client that same year. There could be no bigger contrast between siblings. John was a Rhodes Scholar, basketball star and author favorably mentioned by literary critics in the same breath as William Faulkner or James Baldwin.

Urged to be like his older brother, Robby’s response was “Nah… I’d rather be like (Black Panther Party co-founder) Huey Newton.” Robby chose to be Pittsburgh’s version of “Super Fly,” sometimes posing resplendent in a white floor-length fur coat astride a white Cadillac. Day to day however, he was a desperate, strung-out and drug-addicted street hustler. At the time of the publication of “Brothers and Keepers,” Robby had been in jail for nine years for a 1975 botched robbery/scam that resulted in a death. While his accomplice pulled the trigger on a fleeing fence for stolen goods, one Nicola Morena, it didn’t matter. Participating in a felony where someone dies, no matter the cause, gets you life.

Robby Wideman’s conviction for felony murder got him a life sentence without the possibility of parole. It was that simple.

The 1984 publication of “Brothers and Keepers” generated a great deal of media hype coming after John’s winning the Penn Faulkner Award for “Homewood Trilogy.” “Brothers and Keepers” was nominated for the National Book Critics Award. The idea, with my coming on board in 1984, was to use all of this to achieve a commutation of his sentence. This was to be Robby’s only way out. However, my own Wideman sentence would not conclude until 35 years later, with Governor Tom Wolf’s approval of the Pennsylvania Pardon Board’s May 30, 2019 unanimous commutation recommendation.

During my term of representation, there has been a linear progression when it comes to Robby Wideman’s development that has only increased my faith in him and his cause. I can’t say the same about his brother John.

Robby Wideman deserved to finally be released after 44 years of incarceration. He has been touted for the education that he pursued, his character reformation and his prison mentoring of others. It has since been my hope that his commutation would prompt policymakers to reconsider the fundamental unfairness of the doctrine of felony murder and question the sanity of warehousing an elderly population who no longer represent a hazard to anyone. In the two years following his commutation, it looks as if he has cracked, if not broken, the dam, as more commutations for lifers have followed. Yet, getting rid of the felony murder doctrine seems remote.

I’ve learned something about the behavior and motivation of these two brothers. At the outset, let me emphasize that I’ve never represented John Edgar Wideman, so I don’t owe him any duty of confidentiality. Moreover, he has never confided anything in me. What I have learned about him has been from what has been written about him, all in the public domain. So, I try to reconcile this with my interactions with him. There is John, Robby’s brother. There is also John, the father of a son, turned murderer. My own awe and trust of John as a young lawyer gave rise first to question, then skepticism. Regrettably, age and experience have turned skepticism to outright distaste. Notwithstanding the title and the literary accolades of “Brothers and Keepers,” John proved to be Robby’s “keeper,” but not in the way he would wish to be portrayed. Specifically, I believe John’s decision with respect to court proceedings may have kept his brother in jail for another 20 years.

* * *

The full intergenerational Wideman story can be captured by the phrase “the bad seed,” which John raised in “Brothers and Keepers” and has been cited in coverage of the Widemans ever since. It refers to a seed perhaps implanted at the beginning of time, with violent results erupting down through the generations. It is bigger than both the brothers, pre- and post-dating their generation. Death and suffering are its persistent refrain. Perhaps it explains John’s literary departure from Faulkneresque prose to more violent narrative.

From the age of 15, I was privileged to have as a mentor the African American civil rights activist and eventual Pennsylvania House Speaker K. Leroy Irvis. He launched my representation of Robby, saying he was going to have Robby’s brother John call me. I still hear his seemingly offhand remark back in 1984 that he had represented John and Robby’s father in the 1950s. It was something about a knife fight and killing of a co-worker on a garbage truck and something else about the father trying to fence stolen radios. Irvis had an almost spiritual way of telegraphing messages and themes. I’d like to think that, in the four decades of our relationship, I picked up on most of them. However, here I did not pause and ask for details so as to learn more. I should have. Nevertheless, decades later his allusions return with my learning of recurrent eruptions of “the bad seed” in the Wideman family.

It was in 1975 that Robby Wideman orchestrated a scam, arranging with Black Homewood pals to deliver a truckload, not of radios but stolen TVs, to some white South Side family members who claimed they were a fence for stolen goods. The Homewood threesome were high and had no TVs. And the fence members didn’t have much in the way of money. Robby never thought that a simple scam among two sets of criminals would prove deadly. He was wrong. After giving flight, Nicola Morena eventually died of a gunshot, fired by Robby’s accomplice, which nicked his thoracic artery.

Contrast this to the outright carnage in the next generation: First, there is the violence associated with John Edgar Wideman’s son Jacob, convicted of viciously stabbing a fellow summer camper to death in 1986. Then, in November 1993, Robby’s son Omar was machine-gunned to death after being in the wrong place at the wrong time, having gotten into an argument-turned-street-fight with a gang leader who came away “disrespected” and determined to exact revenge. Omar Wideman died execution-style, riddled with bullets shot at close range to the head and face while he lay in bed.

Perhaps “the bad seed” has been an endless resource, providing John with a career’s worth of material as well as tremendous grief. I used to visit his mother, Bette Wideman, a quiet woman of faith, who worked in a Downtown Pittsburgh floral shop. God only knows how she withstood the relentless body blows over three generations of husband, son and grandchildren.

* * *

Until the 1984 pardon board hearings, I had never physically met John Wideman. He was only a voice on the telephone, coming from what I imagined to be idyllic summer digs for any writer: a cottage in Maine at upscale camp Takajo, owned by his then-wife’s parents. It was, and remains, one of the select places where prominent and well-to-do families offload their kids for the summer. Our phone calls evidenced what I simply viewed as his authoritative presence. As I began to represent Robby, I devoured John’s early books. That authority seemed to be well deserved.

Although we were both from Pittsburgh, John Wideman and I came from very different backgrounds, or so I thought. I was raised in a middle-class Catholic suburb of Forest Hills, later ever proud to explain to others that “I am the only Pittsburgh Jew not from Squirrel Hill.” Other than that, I was lucky to have a rich aunt who sent me to local prep school, Shady Side Academy.

John Wideman was born in Washington, D.C. in 1941, but he and his parents moved soon thereafter to the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood-Brushton, not the tough Black ghetto it was to become years later. After 1945, the Wideman family moved to upscale and white Shadyside. Hard times eventually drove the family back to a very different Homewood, but by then John had made his escape to college. John was never a product of the “hood.” Robby was.

Given the fact that John was considerably older, I did not know of him until my representation began. There was his high school academic and basketball success at Pittsburgh’s Peabody High School, hardly a shabby school at the time. Then in 1959, he became one of only six Blacks accepted to the University of Pennsylvania’s incoming class where he became captain of the All-Ivy basketball team and graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

In 1968, he gained further acclaim by becoming the second Black in history to win a Rhodes Scholarship. He went on to Oxford, England for a bachelor’s in philosophy, playing basketball with fellow Rhodes Scholar, later NBA player, and finally U.S. Senator Bill Bradley. He married fellow Penn student Judith Goldman with literary acclaim and professorships to follow. He entered the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1966 and 1967, mentored by prominent authors including Kurt Vonnegut. Then came a Penn professorship in 1967, followed by posts at the University of Wyoming in 1975, University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1986, and then Brown in 2004. As early as 1983, The New York Times was calling him “one of America’s premier writers of fiction.” In 1984, “Brothers and Keepers” was published. The book was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

For better or worse, the attendant hype about the book put both brothers in the spotlight. Success begat success for John, but not for Robby. His case achieved national media attention thanks to “Brothers and Keepers,” but not a successful outcome. In retrospect, the strategy devised by John, Irvis and me to link Robby’s case with the book publicity may have backfired, leaving the Pardon Board with the sense that one brother’s prominence shouldn’t make it any easier for the other. More realistically, the fact remained that in 1984 Robby had spent less than a decade in prison. It was too soon.

A recent re-reading of “Brothers and Keepers” pulled back the curtain on John Edgar Wideman for me. His interviews and writing are all about society’s racism and where it relegates Blacks, himself included. However, given his career path and those with whom he has associated and who have enabled him, he might as well have been a white prep school grad like me. In conjunction with the 1984 Pardon Board hearing, I saw John Edgar Wideman, the orchestrator. In the same way that Truman Capote was accused of manipulating killers Perry Edward Smith and Richard Hickock so as to best position his famous work “In Cold Blood,” so too was John more than a passive observer of Robby’s plight. There was no coincidence that the pardon effort came with the publication of “Brothers and Keepers.”

This was combined with all of the political swat that could be mustered and all of the media hype that could be generated, including a “60 Minutes” feature conducted by Ed Bradley with Robby at Pittsburgh’s Western Penitentiary. There was talk of a movie to be done by three New York City cops turned successful Hollywood screenwriters. However, they threw in the towel, telling me that John wanted a veto and complete control. In the final analysis, it strikes me that the methods that Capote and Wideman employed with their writing and their own lives ultimately relegated them to being isolated and tragic figures.

Through it all, John’s writing has changed. The romantic throwback of “The Homewood Trilogy” gave way to the introspective “Brothers and Keepers,” followed by books with much more violence. To me, John Edgar Wideman has always seemed inscrutable and elusive. Indeed, it’s like what Washington Post writer Paul Hendrickson said in his interview piece published on Oct. 15, 1990. “It feels as if a man has beckoned you into his house, but then once you’re inside comes up to the white of your eyeball and asks just what the hell you think you’re doing there.” Wideman told him, “My life is a closed book. My fiction is an open book. They may seem like the same book — but I know the difference.” Does he?

* * *

I remember a conversation in the mid- to late-1980s outside of the Philadelphia Free Library before John’s book talk. Innocuously enough I was talking to Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale and another fellow. When I said that I was Robby’s lawyer, Seale told me he was interested in my representing him to promote a book tentatively titled “Barbecuing with Bobby.” I was taken aback, considering his career change and what his detractors would say about what or whom Bobby would be barbecuing. I changed the topic, asking the other bystander how he knew John Wideman. He said that when Wideman was at Penn, he was his pizza delivery guy, matter-of-factly claiming that when it came to payment, Wideman stiffed him.

In 1975, after the robbery-turned-murder, Robby and an accomplice fled Pittsburgh. Three months later, they arrived via stolen car at John’s Wyoming doorstep. John fed and housed them before they left the next morning. It should not have taken a Rhodes Scholar to understand the concepts of “aiding and abetting” or being “an accessory to a crime after the fact.” When later questioned by the police about Robby and a recent convenience store robbery by several Blacks in Utah, John played the race card. He resented the inference that because he was Black, he must have been one of the perpetrators. Was being a professor at the University of Wyoming supposed to give him a pass? Apparently, it worked for John. Back in Homewood, I wonder if the police would give second thoughts to charging someone when it comes to being an accessory or harboring a fugitive. They likely wouldn’t get a pass. But being John Edgar Wideman had its privileges.

In 1985, only 10 years later, violence visited John’s then-hometown of Laramie, Wyo., with the grisly murder of 22-year-old University of Wyoming student Shelli Wiley. She was stabbed repeatedly and had her head bludgeoned. Notwithstanding, she apparently was able to fight her way to her front door and run out, only to have her throat slashed before being dragged back. After being drenched in gas, her apartment was torched. The phone lines were cut.

In 1986, John Wideman’s family left Laramie and moved east to take a position at the University of Massachusetts’ MFA program. According to a March 1989 Vanity Fair article entitled “Seeds of Violence” written by Leslie Bennett, it was only four months after the Wiley killing that 15-year-old Jacob Wideman took his father’s car and ran away. Both were eventually retrieved, with Jacob being sent to a psychiatrist. Judy Wideman apparently found a note written by her son, stating, “Killing solves problems. I think I will murder someone. I am proud. I haven’t been caught stealing.” Clearly, this was an extremely tormented kid. At one point, Jacob Wideman confessed to the Wiley murder, a confession that was later withdrawn. The Wiley murder remains unsolved.

The “bad seed” again erupted in the summer of 1986, obliterating the summer idyll that was Camp Takajo for the Wideman family and the family of another camper. Campers Jacob Wideman and Eric Kane had won “distinction” that summer and were awarded a camp-sponsored trip to travel west to visit the national parks. At Yellowstone, like any other tourist, 16-year-old Jacob selected a keepsake: not the typical tourist postcards or rabbit’s foot, but instead a six-inch serrated blade “survival” knife. That night they traveled to Flagstaff on the way to the Grand Canyon. After borrowing the keys to a counselor’s car, Jacob retired to his hotel room shared with Eric Kane. Come morning on August 13, 1986, Eric Kane was found repeatedly stabbed to death. This time, John Wideman escorted his son to Flagstaff, Ariz. to face the charges. Fast forward to 1988 and Jacob Wideman pled guilty to first-degree murder, presumably to avoid the death penalty.

Naturally, the Kane family was dumbfounded and grief-stricken. Again, it would not have taken a talented wordsmith, let alone Rhodes Scholar, to try to soothe them in their grief. A sincere gesture might have sufficed. Apparently, John Wideman wasn’t up to it. Instead, he added insult to injury by writing the Kanes a letter “forgiving” them for wishing the death penalty for Jacob.

Doubtless, this fed the Kane family’s pursuit of a more than $50 million suit against John Wideman, his wife, and the camp’s owners.

Inside the Kane criminal case file, Phoenix New Times reporter Tom Fitzpatrick found the following statement of Eric Kane’s parents:

“Eric was killed by an animal. Eric was asleep. There was no provocation or ill will… Jacob Wideman deserves no place in society today or at any time. If justice were properly served in this case, he would be sentenced to death.”

Eric’s mother, Louise Kane, said, “I’m sick of hearing about Black and white. This is not a question of who’s Black and who’s white, but of murder.”

Eric’s father, Sanford Kane, said, “I read ‘Brothers and Keepers.’ The man sounds like someone who uses the system to his advantage. But if it doesn’t work out for him, he screams and hollers about how unfair it is.”

The Kane lawsuit faulted John and Judy Wideman and also the camp, given its interview and selection process for prospective campers. The following paragraph set forth the gravamen of the lawsuit:

“61. That at all times hereinafter mentioned, defendant, JOHN EDGAR WIDEMAN, as father and natural guardian of JACOB WIDEMAN, having knowledge of the violent, strange, erratic and abnormal behavior exhibited by JACOB WIDEMAN, and the psychiatric care and treatment rendered to said JACOB WIDEMAN, had a duty towards those with whom JACOB WIDEMAN would come into contact and, more particularly, plaintiff’s decedent herein.”

* * *

In 1996, Pittsburgh lawyer Foster Stewart filed a petition for a new trial in Robby’s case based on “newly discovered evidence.” He had learned that the family of Nicola Morena, the young man who died in the 1975 stolen-TVs-for-cash-scam, had filed and settled a medical malpractice suit contending that, but for the negligence of the attending hospital and physician, Morena would have lived. Since my 1984 Pardon Board representation, I had moved across the state and was no longer involved with Robby’s case. I knew nothing about this development. Neither apparently did the district attorney or Robby’s defense counsel. It took from 1996 to 1998 for Judge James McGregor to even allow a hearing on the petition. Then I got a call from Dennis Harrington, a colleague of Stewart’s. Stewart had died and left behind a briefcase of papers, some of which had my name on them.

I traveled to Pittsburgh. That briefcase was handed off to me in Judge McGregor’s courtroom. I was now back on Robby’s case with Attorney Stewart’s novel theory, eventually achieving a ruling just before Thanksgiving of 1998 that Robby Wideman was to be freed on bail for a new trial. The theory was simple. As the Morena family suit claimed that it was the negligence of the doctors and hospital that killed their son, this raised the question of the actual causation of death. I called the family’s medical expert, who testified as to the fundamental inadequacy of care received by Morena. I also called Dr. Cyril Wecht, who had been the Allegheny County Coroner in 1975. He testified that, had he known of the medical malpractice that had been alleged, he would not have recommended the felony murder charges on which Wideman was tried. I argued that, when it came to Robby Wideman, at the very least, a new criminal trial was necessary so that a new jury could weigh the malpractice claims and then decide the causation of Morena’s death. The judge eventually agreed.

For the final hearing, the courtroom was packed, including John Edgar Wideman and the national media. In a brief hallway conversation, John admonished me to stick to the facts and not play the race card. Shortly afterwards, he and I met at The Today Show’s New York City set to be interviewed by Katie Couric. While I didn’t exactly expect business attire for him, I was shocked to see him dressed in dashiki and skull cap. It looked as if I’d be joining Malcolm X, just back from Africa, on national television. Beforehand, I asked him what the message should be and what we should each emphasize. His dismissive remark was something like, “I can’t talk now. I’m in my own mind.” My wife vividly remembers his coming out of his own mind long enough to remind me how lucky I was to be handling this case, implying that I should do it without charge.

In the interview, Couric asked Wideman why he wasn’t able to bring the proceedings earlier. He answered that he wasn’t in a position to get able representation until now. He was making me look like some fat-cat lawyer — an F. Lee Bailey-type sophisticate — that he could only recently afford. Given his payment history with me, that infuriated me. But I wasn’t going to show it on TV, so I just sat there incredulous, stifling it all with a smile. After the interview, John Wideman and I parted separately without saying anything further.

Political forces were building after Judge McGregor’s grant of a new trial that week before Thanksgiving 1998. He also ordered that Robby be freed on bail. However, District Attorney Stephen Zappala blatantly defied Judge McGregor’s court order freeing Robby, illegally directing prison officials to hold Robby pending an appeal. Shortly afterward, higher courts revoked Robby’s bail and reversed the granting of the new trial. So close, but so far.

This left me only with the avenue of personally going after the district attorney for contempt of court for defying the order to free Robby on bail. Although the disregard of his order was clear, Judge McGregor sought not so much an explanation for what the D.A. did, but simply wanted an apology. I attended one meeting in the judge’s chambers where the first assistant D.A. refused to acknowledge the obvious. An apology would have defeated my application for a contempt hearing. However, receiving nothing but apparent disrespect, the judge came around to my thinking and was going to schedule a hearing on my contempt motion.

I felt that if I could get that contempt hearing, perhaps I could negotiate something with the D.A.’s office on Robby’s behalf. What the judge really wanted was not a new trial, but a settlement where Robby’s time served would have been enough. And Robby would be free. A contempt hearing was the only pressure point left. I felt it could work.

Then, I received an 11 p.m. call from John Edgar Wideman. “Mark, we’ve decided not to go with the contempt hearing.” His calm, Alexander Haig-like “I’m in command here” attitude got me awake and focused. John thought there was some political maneuver he could do that would help — some political fix with the D.A. Never mind the fact that every conceivable effort had already been made by state and local players. But legal and rational argument got me nowhere. I ended the call with, “Well John, I’m scheduled to fly to Pittsburgh tomorrow and I’ll be meeting with the client, your brother. After all, you aren’t the client. Let the client decide how to proceed.”

The next morning at Western Penitentiary, I met with a distraught Robby Wideman. It was clear to me that the contempt hearing against the D.A. was his last and best chance of ever getting out of jail. Apparently, however, blood ties trumped legal strategy. Robby had tears in his eyes. The decision had already been made. I felt it necessary to formally withdraw my appearance from further representing Robby Wideman. Shortly thereafter, I filed the papers. With my appearance gone, Judge McGregor had no choice but to cancel the contempt proceedings. Case closed. Robby would remain in jail for life.

John’s ripping the rug out from under me was the last straw. His career had been made decrying the injustice that Blacks suffer at the hands of the system. Just when Robby could have benefitted from the justice system, John Edgar Wideman pulled the plug, ending what chance Robby had for freedom at the time.

* * *

Time passed, and I moved on personally and professionally. My two young sons who attended The Today Show session grew into parents themselves. I’ve been lucky enough to chart my own path in my own law practice. With time, some of the prominent players in Robby’s search for justice have met their end. Judge McGregor said that he would go to his grave considering what happened to Robby as being the worst injustice of his career. He did.

Notwithstanding, there was always regret in the back of my mind for Robby Wideman and what I considered to be my sole piece of unfinished business. I learned much later that a prominent prisoner’s rights attorney had filed a federal habeas corpus case for Robby based on the McGregor proceedings. That was dismissed out of hand. There were also more Pardon Board applications, which went nowhere. After all, since the last decades of the 20th century, the atmosphere for clemency was worse than when I was involved in 1984. Governor after governor, not just in Pennsylvania, touted the “tough on crime” slogan, engaging in an orgy of prison-building.

Eventually, an unlikely Pennsylvania politician surfaced. Tom Wolf became governor in 2015. Wolf was a trust fund baby who never had to pass through a political party pecking order to get elected. His campaign ads featured him in a cardigan sweater, Jimmy-Carter-style. He struck me as being bookish and too cerebral for the rough-and-tumble of Pennsylvania politics. To this day, there seem to be few who really know him. He would be running for a second term to begin January 2019 with a new lieutenant governor, whose sole responsibility under the Pennsylvania Constitution is to head the Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole. I thought that a window might be opening.

So, after almost 20 years, I got back in touch with Robby, told him that his was my bucket list case, and that it was time to proceed. In the summer of 2018, I looked at my old files and then returned to Pittsburgh to review the transcripts of the 1998 McGregor proceedings. It was none other than Chief Judge Jeffrey Manning, who secured the files and housed me in his chambers for my multi-day review. Ironically, Manning had been the prosecutor in Robby’s murder trial.

I was disturbed to find out that, as recently as August 2018, the Board of Pardons had again turned Robby down for consideration. Getting what would amount to a reversal only months later would require handstands. Something other than the conventional, “I’m sorry… I’m rehabilitated” approach struck me as being necessary. The board had to learn about the travesty of the McGregor proceedings 20 years before and what I felt was the D.A.’s obstruction of justice. In my legal research, I found a quote from, of all people, former U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who said that the pardon process was the ultimate check upon an infirm judicial outcome. That had to be the theme — that something went wrong when it came to the judicial process for Robby Wideman and that redress could be found only through a commutation.

With my turning 65, my wife and I decided on a change of venue for six weeks. In the winter of 2018–2019, we rented a place in Stowe, Vt. and drove up with a station wagon full of Wideman documents. Afternoons were dedicated to my writing a Pardon Board “Application for Reconsideration.”

There was something serendipitous about sitting down that first afternoon for what would be more than a month of drafting. I got a telephone call:

“Mark… With this new guy [John] Fetterman being elected in November and now sworn in as lieutenant governor, we’ve got a real shot.”

I didn’t recognize the caller. “May I ask who this is?”

“Jeff Manning.”

I didn’t feel that Judge Manning and I were on a first-name basis. But he was correct. For Wolf’s second term, his lieutenant governor would be the upstart former mayor of Braddock, the depressed steel town just outside Pittsburgh. You’d never know from the goatee, black T-shirt, biker look and tattoos that mayor-turned-lieutenant governor John Fetterman was Harvard-educated.

“Sorry, Judge. You caught me off-base. But your timing is wild. I just sat down and started drafting a Petition for Reconsideration.” What were the odds on the timing of that call? We were exactly on the same page.

The petition came to be filed with the Pardon Board in March 2019. This time I did not want John involved. It was not about his interference 20 years before, but simply because I did not want John’s baggage. Involving him would shift the media focus from Robby to John and the violence associated with his own son. The Wideman “bad seed” stories would overshadow everything, rendering Robby a footnote. Those were my terms.

In early May 2019, I traveled to Harrisburg for a Pardon Board meeting. In addition to its other powers, the Pardon Board is responsible for recommending to the governor sentence commutations, which is what we were seeking. It turned out to be not a meeting at all, but a conference call conducted in a room in the Capitol basement. Staff were present, but the five board members who included the lieutenant governor, attorney general, and three public members were only present via problematic cell phone connections. There were only five cases involving lifers such as Robby, but that group came at the end of a long agenda of about 100 other cases. These cases were buzzed through like a farm implements auction. Service was spotty and some board members weren’t clear on who they were voting on — voting and then changing their votes when they realized that they were on the wrong agenda item. I found it amazing that lives hung in the balance of this craziness. To everyone else, it seemed routine.

With presentations not allowed, there was nothing for me to do but sit and wait. I sweated through my clothing in what, for others, was air-conditioned comfort. We finally came to the last category: whether any of the five lifers would be placed on the board’s next public session agenda for consideration of a commutation. While some applications were tabled, Robby’s was endorsed 5-0 for a hearing to be held on May 30, 2019. I left the room drenched but elated. Supporters raised John Wideman’s participation in the upcoming hearing, but I wouldn’t budge.

The official hearing where the actual vote would take place was to be the Pennsylvania Capitol building’s Supreme Court Chambers, resplendent in gold leaf and stained-glass. However, Robby and the other prisoners were not permitted to attend the formal session. The night before, in the austere digs of the Dauphin County Prison, Pardon Board members grilled Robby in a crammed conference room furnished with metal prison-issue chairs, some broken, and a metal conference table. Uncoached and under rapid-fire questioning, Robby handled it all. He repeatedly took responsibility for all that he had occasioned without excuse, frustration or anger in his voice. No cards were played.

At one point I simply had to cut in and remind those board members why his application for reconsideration was filed. I said, “I find it nothing less than remarkable that Robert Wideman is neither angry nor bitter about being robbed of his freedom by a district attorney who ignored a lawful court order. Robert Wideman has consistently been accepting and gracious. However, I want you to know that I am pissed and will ever remain so.” Board members looked down and then moved on to the next applicant.

The next day at the formal hearings, the only witness I called was Robby’s former prosecutor, Judge Jeffrey Manning. The room went silent as the weight of Judge Manning’s presence clearly sunk in. The motion was made to recommend commutation for the governor’s approval. The vote was unanimous. The room erupted. On my way out, a supporter approached me and said, “You were right not to include John.” A little more than a month later, on July 2, 2019, the governor’s signature freed Robby from 44 years of prison. It was over.

* * *

Law students are taught never to take things personally. I flunked that class. I hold John responsible for possibly squandering 20 years of his brother’s life. Thus, I have not missed interacting with him. This was to change on Feb. 14, 2020, the date that Pittsburgh’s Duquesne University had chosen for a panel discussion about Robby Wideman’s case.

That morning, I took a cab up to “The Bluff,” Pittsburgh jargon for the windswept plateau occupied by Duquesne University. I was dropped off at the student union. Standing in the Starbucks line, I wondered what 78- or 79-year-old John Edgar Wideman would look like. What would he wear this time? Would he replicate the Malcolm X dashiki and skull cap look from our “Today Show” interview? Or perhaps, given a career of professorial positions, he’d wear something academically authoritative for the occasion.

Following others now streaming in, I found the large designated room. After so many years, some people recognized and approached me, while others congregated among themselves. I looked around. Those present included Judge Manning, Dr. Cyril Wecht, the Pennsylvania State Corrections Secretary and others. Prior to the start of the program, I was able to take a picture of a handshake between Robby and Manning — their first reunion after 44 years, this time with Robby as a free man.

Then a man in a black set of warm-ups approached. He was still tall, but this time John Edgar Wideman did not strike me as being so formidable. He thanked me. I let it go, relieved that the reunion was over.

Naturally, John opened the conference with that professorial air, a profound air of certainty and conviction. Listening carefully and taking notes, I was convinced that what he said came from stream-of-consciousness meandering. He opened by saying that numbers and pieces all converge in Pittsburgh. What did that mean? He reminded us that it was Valentine’s Day, noting that while we are all evil and separated from each other, that there is a part to love and to celebrate in each of us and that today was dedicated to his brother’s miraculous reappearance.

John proceeded to tell us that 30 years ago he was in Johannesburg, South Africa when Nelson Mandela walked out of prison. John said that he then felt as if he were welcoming a brother. It reminded me of those funeral speeches which are supposed to be about celebrating others, but which are more about the speaker.

Were we meant to be impressed that famous author John Edgar Wideman was on the Mandela guest list? What was the common theme? Robby Wideman never considered himself a political prisoner. While Mandela’s freedom was miraculous given the circumstances, was Robby Wideman’s similarly miraculous? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

John then went onward, saying all the right things about the wonder of family, the recent birth of a grandchild for Robby, and that Feb.13 marked the birth of his own son, Jacob, whom John simply described as a “prisoner.”

John then read a work in progress about Robby’s “homecoming.” John described a reunion on his own Manhattan turf as he waited for Robby’s train at New York City’s Penn Station. John detailed his own mental state during his wait as “running early and scared,” fearful of “glitches.” It had been 44 years since he had seen Robby outside of a jail. John spoke of waiting for Robby’s train to arrive below ground, as all trains do in New York City’s Penn Station, where they disgorge their passengers in deep darkness. They then walk or take the escalator up to the arrival gates. John took literary flight in describing those from below as faceless dead souls clambering over one another to rise, for deliverance. He described his looking down at the darkness, like the dark water, where the slaves willingly jumped from their slave ships with no regrets, arms raised to the heavens, like a defiant fist in the face, sinking into oblivion with no place to be, but gone.

He extended the dark metaphor. Like the deep dark water, prison strips away time. Prisoners are desperate slaves, with no room in the boat. Both places render men “no place but gone,” stripping away time with no evidence of being, substituting emptiness for being.

John noted that even upon his release, Robby’s time would still not be his, to be stripped of another year having to live in, or report to, a halfway house.

Then there were the imponderable “glitches,” i.e., all the things that could go wrong that would prevent Robby from making it to John. John spoke of the fact that the universe presents a host of imponderables otherwise interrupting our lives.

I pondered back to 20 years ago.

At some point after his presentation, someone in the audience asked what should have been done about the district attorney’s having Robby held when he should have been released. I wondered how John would answer this one. It was an amorphous: “We all have an obligation to denounce injustice” or some such pablum. What was his obligation?

After a luncheon for all the presenters that included too much in the way of small talk, I left for several hours and then came back to Duquesne to team-teach a class with Robby and John. The most notable part of the talk came after the class was concluded. John, Robby and I were walking out of the building. I told them about where I was in terms of trying to get Robby a job. With a laugh and cocked head, John said, “Yeah, get him a job before I have to put him on welfare,” sounding like some preppie I might have gone to school with.

As I close out my files and the decades spent on my bucket list case, I think of two brothers. When it comes to Robby, I am an admirer of his humility and acceptance of responsibility. I am pleased that he finally got the justice that he deserved, as a result of using what our justice system affords. When it comes to John, I don’t feel the same qualities are there.

Editor’s postscript: Pittsburgh Quarterly contacted John Edgar Wideman to give him the opportunity to respond to this story, which was described as being critical of him in several aspects, but he declined to be interviewed.