Bring Back the Paddlefish

A century ago, as work neared completion on the region’s locks and dams and Pittsburgh was producing half of the nation’s steel, paddlefish disappeared from the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio rivers.

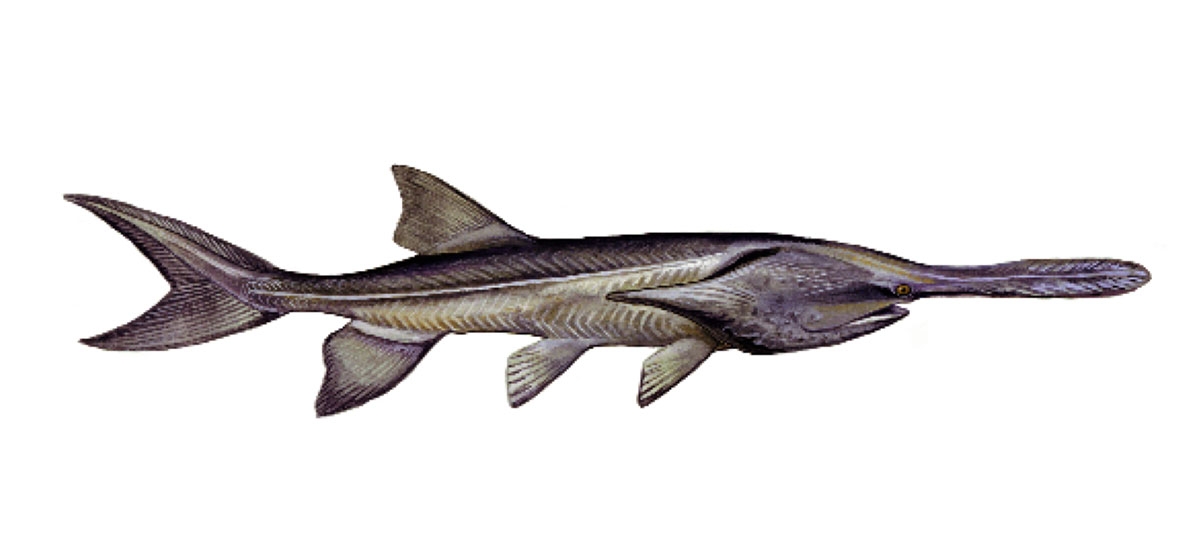

A cousin to sturgeon and equally coveted for its roe, this curious-looking creature with the spatula-like snout used to thrive here—ranging great distances and foraging for zooplankton in local waters. Although as old as the rivers themselves, the Polyodon spathula could not survive the Industrial Revolution.

“Pollution decimated its habitat, and the locks and dams added to its demise. The last known catch of a wild paddlefish in western Pennsylvania was in 1919 at the mouth of the Kiskiminetas River,” said David Argent, a fisheries biologist with California University of Pennsylvania, and one of a team of scientists now trying to restore the species to this part of its native range. West Virginia and New York have similar programs. While locks and dams remain a challenge, tighter controls on some industrial emissions since the Clean Water Act of 1972 make such an undertaking possible.

Using fertilized eggs from Kentucky, the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission has been raising paddlefish since 1991 at the Linesville hatchery near Pymatuning Reservoir and stocking them as 5-month-old fingerlings in the Allegheny and Ohio rivers. About 13,000 a year are implanted with tags smaller than a grain of rice so scientists can distinguish them from the wild paddlefish they hope to capture.

So far, only “stockies” have been caught—including some that have grown to 50-plus inches and 42 pounds—but every five years, Argent renews his search, combing the rivers for evidence of natural reproduction.

This year, he is intensifying his efforts. In addition to trawling for adult and juvenile fish, Argent will try to capture larval paddlefish in driftnets set near Twelve Mile Island at Harmarville and Six Mile Island below the Highland Park Dam on the Allegheny—a labor-intensive process that requires checking nets every five hours. While the odds may be akin to finding a needle in a haystack, proof that paddlefish are breeding in the wild is pivotal to the future of the restoration program, since the goal is to generate a self-sustaining fishery.

More than $600,000, mostly in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funds, have been poured into the effort. And while there is no expectation of creating a sport fishery similar to those elsewhere in the Mississippi River Basin, Argent and others are intent on resurrecting a part of the region’s natural heritage.

“Will the food web collapse if paddlefish aren’t there? No,” said Argent. “But they belong in our rivers. Restoring the fishery is the right thing to do.”

At times, it may seem tantamount to swimming upstream, since there are concerns the species—known to migrate more than 30 miles a day during springtime spawning runs—may have difficulty adapting to the navigational pools created by the locks and dams.

Paddlefish get a boost in spring when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers performs conservation lockages so that they, walleyes, and other species can make arduous migrations. They also tag along with boats and barges, although the Army Corps has warned that federal funding cuts could limit lock-throughs on the Allegheny, with its declining commercial traffic, beyond next year.

“There’s been enough opportunity for paddlefish to move, because we’ve seen those stocked in Freeport as far up as the base of the Conemaugh and Loyalhanna dams,” said Rick Lorson, a biologist with the fish and boat commission and the lead scientist in the paddlefish program. “Those stocked on the Monongahela at Morgantown have been located as far up as Maxwell lock and dam [in Fayette County].”

But even paddlefish that adapt to more confining pools are so finicky about water temperature and flow that, if their requirements aren’t met when it’s time to reproduce, they won’t spawn, Lorson said, noting that it takes about a decade for a paddlefish to mature sexually. “If water is too low and cold, they may reabsorb their eggs and skip a year or even two.”

The Army Corps could enhance conditions through controlled flooding, Lorson said, “but it would take considerable coordination to protect people and property along the river. It’s a long shot, but it’s been done out West, so it’s not out of the question.”

A new study planned by the fish and wildlife service could provide some of the best clues yet about paddlefish behavior, including where the elusive creatures go soon after they are stocked.

Biologists at the service’s Northeast Fishery Center in Lamar, Clinton County, Pa., plan to implant 50 fish with electronic tags, and then track their signals with receptors installed at various points along the rivers. With tags costing $380 apiece and receivers $1,500, it will be a costly but valuable undertaking, said fisheries biologist Steve Davis. “We expect to learn whether fish are heading downriver to the Mississippi right off the bat or going to a favorite pool closer to Pittsburgh.”

Folks who have encountered paddlefish think the effort is worth it. The 48-inch specimen that walleye angler Terry Schrader unexpectedly caught one night in the tailrace of the Kinzua Dam gave him an experience he’ll never forget. “I didn’t know what I had on, but it took off like a steelhead… peeled my line off pretty quickly. It was the most amazing fight I’ve ever had.”

“When I got it to shore, I realized what it was from pictures I’d seen,” said Schrader, of Youngsville, in Warren County. He immediately released the fish, unharmed, as required by law. “With that silvery skin and 12-inch snout, it was very unique looking.”

Aside from its odd appearance, the snout—or rostrum—helps the paddlefish function in a number of ways. It contains a network of sensors that detect electrical impulses emitted by tiny organisms that paddlefish consume. Unlike species that ambush prey, paddlefish feed by moving through the water with their mouths constantly open.

Although studies indicate that a paddlefish can forage even with its rostrum removed, it’s not as effective, Lorson said. “We think the rostrum actually helps funnel water into the fish’s mouth and out through the gillrakers so the fish can maximize its food intake.”

And there is another purpose, he said. “The rostrum helps the paddlefish maintain balance as it maneuvers through the water.”

Doug Laney of Turtle Creek can attest to the fish’s unusual grace, having caught a 57-inch paddlefish while targeting walleyes on the Allegheny near Kittanning. “I thought my eyes were playing tricks on me when I saw what I had on my line,” he said. “When I released him, he turned and kind of looked at me with those beady eyes. I gave him a little push and he swam away—and so elegantly! It was a beautiful sight… almost a spiritual experience.”

Learn more about paddlefish and see this unusual creature in action: visit the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at fws.gov/midwest/fisheries/paddlefish.html or Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission at fishandboat.com.