Blending Image and Word

Ekphrasis first began as a rhetorical form used by the ancient Greeks. Defined by Webster’s as “a literary description of or commentary on a visual work of art,” it remains one of the oldest forms of artistic analysis, dating back to Homer’s description of Achilles’ blacksmith god-created shield in The Illiad. This form of writing enabled writers to bring physical nuance to a thing that existed only in the imagination. Over the years, ekphrasis has evolved, allowing poets to capture both visual representation with words (useful in a time before images could easily be reproduced or transmitted) while, more recently, adding a more subjective, transformative element to the pictorial through word choice, perspective and allusion.

By bringing the literary to the visual, paintings and photos become reinterpreted and reimagined on the page, with the speaker’s tone or level of description adding irony or metaphor. Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn” remains the most popular example of ekphrasis, with Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts,” a favorite for its ability to render Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s sixteenth-century masterpiece Landscape with the Fall of Icarus with a sense of poetic whimsy.

In more recent times, Larry Levis created powerful poems by using as inspirational source material a snapshot of the cemetery where Garcia Lorca is buried as well as Josef Koudelka’s powerful “Gypsies” photo series, each of these images becoming imbued by both what Levis sees in them and how they intersect with the world he inhabits. Locally, Homestead poet Robert Gibb holds the ekphrastic mantle by finding fresh perspectives in the images shot by photojournalists including W. Eugene Smith and Teenie Harris, both of their black & whites memorializing the grittiness of an industrialized Pittsburgh no longer present.

It’s in this vein that Pittsburgh Quarterly hopes to bring a renewed sense of how photography and poetry can play off one another, creating something more emotionally resonant. In this installment of PQ Poem, we’ll be featuring three ekphrastic pieces by New Jersey-based up-and-comer Aaron Fischer paired with photographs by mid-20th century New York City crime/street photographer Arthur “Weegee” Felig that inspired Fischer’s thoughtfully imagistic and engaging writing. We hope you enjoy and look forward to bringing more features like these to our readers. —Fred Shaw, Editor PQ Poem

Weegee: The World’s Greatest Photographer.

That’s how he billed himself, when he wasn’t “Weegee the Famous.” He was Arthur (Usher) Felig, the immigrant son of immigrant Jews who arrived in this county in 1909 and settled on Manhattan’s Lower East Side—the neighborhood that provides the backdrop for the gritty photographs that make up his most important work.

That much at least is certain. Where he got the name “Weegee” is less so. He claims it was a variant of Ouija board, mirroring his uncanny ability to arrive on the scene of murders, stabbing, fires, suicides, and accidents before the cops and firemen. (He also claimed that his elbows itched when something was about to happen.)

He was restless, driven, ambitious, and consumed with the ideas of fame and success. He spent ten years driving around the Lower East Side at night and lived in a single room across from police headquarters. He also had a darkroom in the trunk of his car, so he could develop his photos almost immediately and rush them to editors at the tabloids and later to PM and Life magazines.

He was probably a genius—of both self-invention and photography. He was the first street photographer and arguably the first news photographer. He gave New Yorkers in the ‘30s and ‘40s a window into a city they didn’t know existed—before urban renewal, before Weegee’s beloved slums were leveled.

Weegee: On the Spot

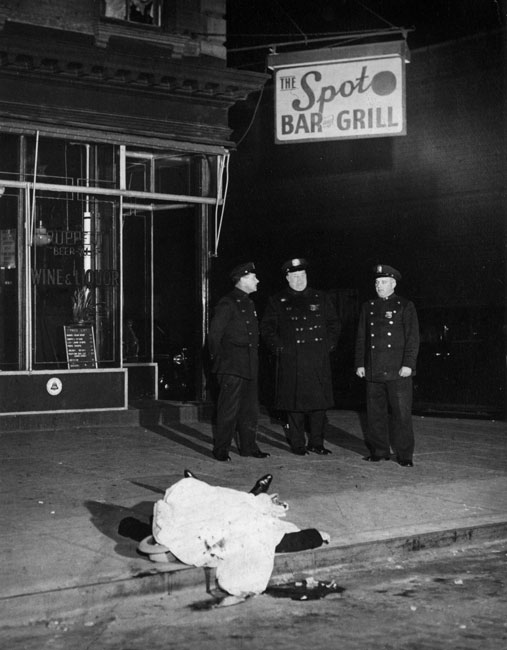

The shot is classic Weegee: three cops

and a corpse in front of the Spot Bar and Grill,

the dead man mostly covered up with a tablecloth

so all we see is an arm flung out to break his fall,

the toes of his polished shoes, a pearl-gray fedora

resting on its crown that told the world its owner

was somebody, a sticky puddle of blood in the gutter

flecked with cigarette stubs and gum wrappers.

What Weegee wanted was to transform the jumble

of every day into the inevitable. In just a second

the coarse scumble of fog pierced by a few glimmers

of chrome will tatter and shift. One of the cops on

this cold corner will hawk and spit. Weegee’s waiting,

watching through the viewfinder. In just a second

everything will start flying apart, like stars in the Milky Way.

He trips the shutter.

Weegee: The Victim of a Motor Accident Lies by the Side of the West Side Highway in New York, Covered by a Sheet

How big the dead man looks in daylight,

under the sky’s gray scrim, a few stalled

clouds building a threadbare thunderhead

over what must be Jersey, and how unlike

Weegee’s more famous shots: a corpse

wedged in a doorway, dark as a funerary niche,

or propped against the palings of a church

like a drunk parishioner waiting for early mass.

Two cars blur by without casting shadows

in the gray light. The victim grips the steering wheel

in his fist, where Weegee posed it—so much

for only photographing “what’s real.”

The driver’s other hand is half tangled in the sheet

tossed over him. We can see an argyle sock,

the scarred soles of the shoes he tied

that morning, getting dressed for work.

Weegee: Young Man Smoking a Cigarette After a Car Crash

Leaning over as if to kiss the blood

from his friend’s broken face, the boy holds

a cigarette between his smudged, blunt

fingers, offering it to the wound

that was his buddy’s mouth, the delicate

damaged head harbored by his other arm.

The side mirror recasts them in close-up,

so we almost miss the third who’s joined them

at the driver’s jagged window—eyes barely lit

by the flash, his face a dark moon—

as if he wants to climb into the car, as if

he wants to savor fear’s taste and tang,

the body’s acrid flush of acid,

the chill beads of sweat pooled at the crotch.

Why Weegee

I didn’t start with Weegee. In fact, I sometimes think Weegee chose me as much as I chose him.

I wanted to learn to write sonnets. I knew from working with other forms—pantoums and villanelles, say—that formal constraints could push me to discover a far more “charged” vocabulary than I could tap into otherwise.

And I didn’t want to write about myself. I wanted to find a subject that was beyond the expected scope of the sonnet (though the more sonnets I read the more I realized nothing was out of bounds).

As melodramatic or unlikely as it sounds, I was leafing through my battered copy of Naked City—Weegee’s first and best book—when I came across a shot of a bakery truck driver killed in an accident. No one was looking at the driver, his whites “rucked with blood” or at the loaves of bread scattered in the street.

This was something I could write about, this grainy black-and-white world with its corpses shrouded in newsprint, its bloodied teenagers sharing a cigarette in a stolen car, a drunk sleeping under a funeral home canopy—the “two-bit nobodies” that Weegee paid such tender attention to.

And the sonnets? If you look at “Weegee: Young Man Smoking a Cigarette After a Car Crash,” and allow for slant rhymes, you can see the sonnet structure that supports it.