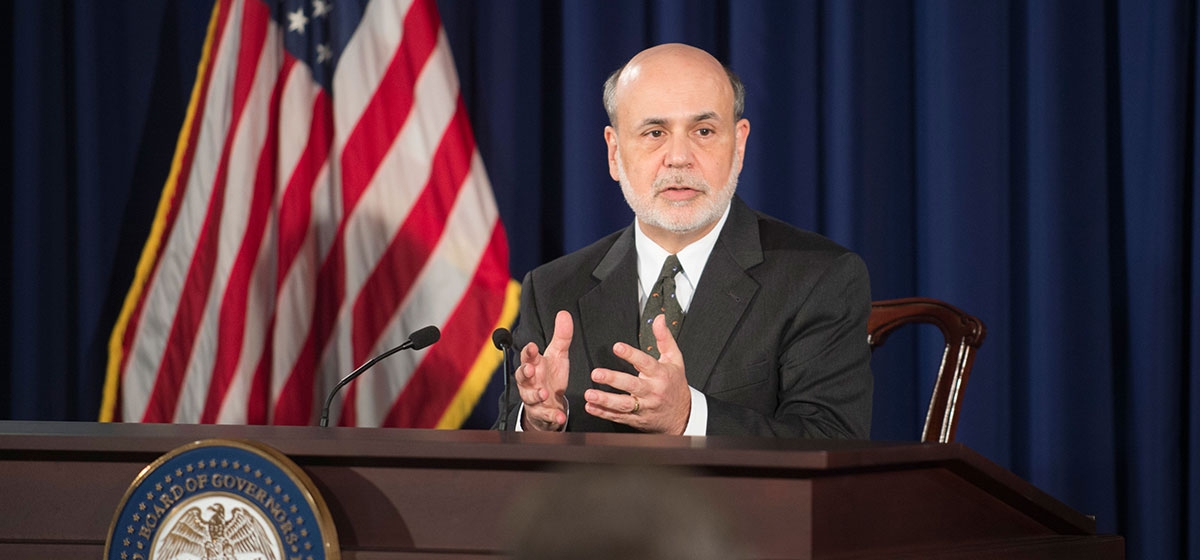

Bernanke’s Blunders

We’ve assessed the successes and failures of central bankers in the 1930s. Now let’s turn our attention to their modern counterparts.

I will argue that, unlike the earlier central bankers, whose record was mixed but a net positive, our modern central bankers have done almost everything wrong—and for 30 years running. To wit:

Like the earlier Fed, which failed to rein in the 1920s economic boom, Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke proved themselves incapable of “taking away the punch bowl” no matter how badly it needed to be taken away. These failures led directly to the Tech Boom/Bust and the Great Financial Crisis.

Once the Crisis began, instead of doing his utmost to maintain confidence levels among businessmen and consumers (and Congressional representatives), Bernanke did everything he could to convince people that the crisis was even worse than it was.

The Fed and Treasury allowed Lehman to fail catastrophically, then used that failure as an excuse to take control over the American economy.

The modern Fed did in fact prove accommodative during the 2008–09 recession, but when the recession ended in 2010 the Fed Governors, their egos having exploded to gargantuan scale, couldn’t let go. They kept injecting more and more liquidity into the system even though it was obviously proving to be counterproductive. They were utterly convinced that the vaunted US economy couldn’t function without their personal intervention.

Finally, the Fed has now managed to paint itself into a corner: it has shot its wad and has little ammunition left to fight the next, inevitable recession.

Let’s look at some of these criticisms separately.

The failure to rein in risk-taking

Alan Greenspan famously kept interest rates so low for so long that a phrase was invented to describe it: the “Greenspan put.”

Investors knew perfectly well that Greenspan had their backs and they responded accordingly, by driving asset prices to the sky and taking absurd risks with their money. Greenspan himself knew what was going on—recall his famous “irrational exuberance” speech—but he lacked the courage to withdraw the punch bowl.

Eventually, he even lacked the ability to do the right thing. By the end of the 1990s so much capital was relying on the Greenspan put that if the Fed had raised interest rates that would in itself have precipitated a crisis.

Greenspan loved being a hero, loved being “the second most important man in the world.” But he simply lacked the moral grit—unlike, for example, Paul Volker—to act responsibly. As a result, prices rose to the sky and then, inevitably, collapsed. The Tech Bust destroyed billions and billions of dollars of investor capital and Greenspan was ridden out of town on a rail.

Unfortunately, Bernanke was even worse. Following the Tech Bust and the Asian Financial Crisis, Bernanke sensibly kept interest rates low. But he then kept them so low for so long that a phrase was invented to describe it: the “Bernanke put.”

Does this sound familiar? Investors knew perfectly well that Bernanke had their backs and they responded accordingly, by driving housing prices to the sky and taking absurd, highly leveraged risks with their money. Unlike Greenspan, Bernanke didn’t seem to understand what was going on: he famously opined that housing prices were just fine.

Bernanke’s cluelessness led directly to the Global Financial Crisis, by comparison with which the Tech Bust was a quaint blip in the markets. Why wasn’t Bernanke also ridden out of town on a rail? Because, my friends, there is no justice in the world.

Precipitating panic

As the Financial Crisis began to roll itself out, beginning in the summer of 2007 and accelerating rapidly with the collapse and rescue of Bear Stearns in March of 2008, people were naturally getting nervous. Did the Fed act to restore confidence? No, the Fed fed (if you will) the panic. Speaking to Congressional leaders on a Friday, Bernanke notoriously told them to do exactly what he said “or you won’t have an economy on Monday.”

This was no way for the head of the Federal Reserve Bank to behave, and Bernanke should have known better because he had role models in Pierpont Morgan (during the Panic of 1907) and FDR (during the banking crisis of 1933). Mario Draghi would do the same for the EU in 2012.

The Lehman fiasco

When Bear Stearns began to teeter on the edge in March of 2008, the Fed experienced its brief-but-finest hour. Although equity holders in Bear wouldn’t agree, arranging for Bear to merge into JP Morgan resolved what might have been a much bigger crisis. The equity owners in Bear were virtually wiped out—Bear merged into Morgan at a price of $10/share, whereas a few months earlier that stock had sold for $133/share.

But so what? That’s what taking equity risk means. If the board and shareholders of Bear weren’t paying attention, were happy to accept the high returns Bear was delivering by taking high risk, so be it. You reap what you sow.

Unfortunately, when the Lehman crisis raised its ugly head, all the Fed could think of was to “do another Bear.” But there were two problems with this approach: Lehman was much bigger than Bear, and the markets and the economy were even more wobbly by then.

When a merger partner couldn’t be found, the Fed claimed that it had no choice but to let Lehman fail because the Fed “didn’t have the legal authority to save it.” The supposed reason for this was that Lehman didn’t have sufficient collateral to support a Fed loan to Lehman to stave off collapse.

This whole notion is so preposterous that one hardly knows where to begin. So, just for the hell of it, let’s begin with our old friend, FASB 157. Actually, let’s begin with it next week.