A World Leader

Sitting in the bright, airy café at Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, Richard Piacentini stamps his foot on the floor. The tiles he thuds against are simple white squares. However, that hardly noticed floor has proven to be both bane and catalyst to a sea change in thinking about every aspect of Phipps’s operations.

In his nearly two decades as executive director of Phipps, Piacentini has overseen the beloved Oakland institution’s transformation from being Pittsburgh’s take on the standard botanical garden to an internationally recognized leader for environmentalism in the field. In 2005, Phipps opened what turned out to be the greenest (most environmentally sustainable) conservatory visitor’s center in the world; a year later, the institution opened the similarly forward-thinking production greenhouses and Tropical Forest Conservatory. But rather than rest on Phipps’s laurels, Piacentini is stamping his feet.

The Welcome Center, including this café, was being built to LEED standards (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), a system that employs points earned for various green building practices towards a certification of the building as Silver, Gold or Platinum. One aspect of LEED building standards is that materials be sourced locally, saving the energy necessary to transport materials around the world.

“I came into this café when they were putting these tiles down,” Piacentini said. “I noticed on the box it said, ‘Made in Turkey.’ So I called one of the people on the project: ‘What’s this made in Turkey—I thought we were supposed to use local materials?’ He said, ‘Oh, we already got that point.’ In LEED, you reach a certain level, you get the point. Once they’d done that, they went back to the old way of doing things. I said, ‘Wait a minute—we’re not doing this just because we want the LEED certification. We’re doing this because we think it’s the right thing to do.’ It was too late to change the tile—these are Turkish. But it set off a revolution in the way we were thinking.”

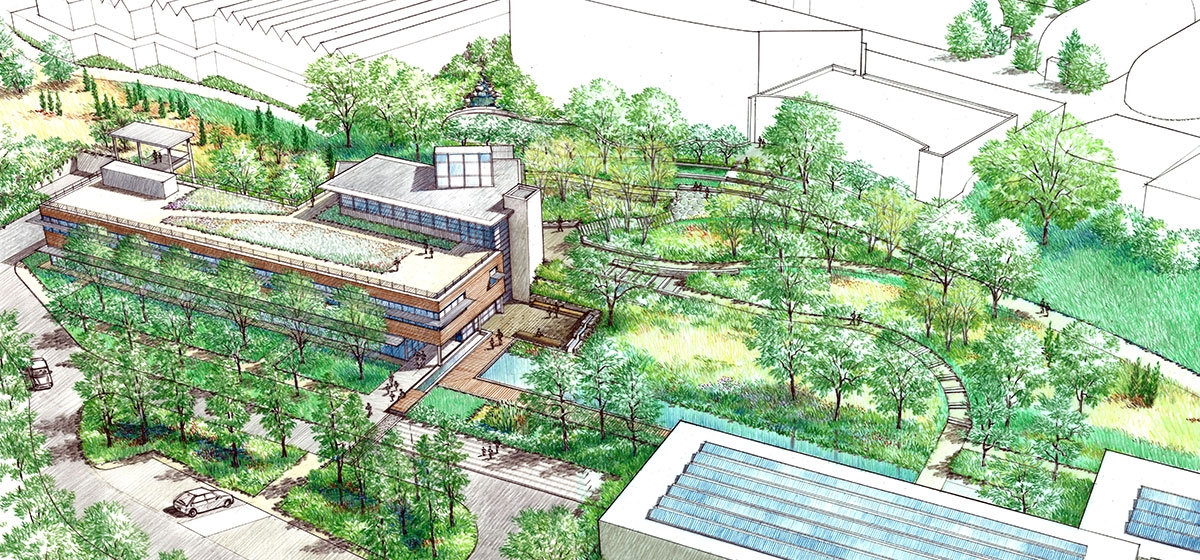

Seven years later, Phipps is preparing to reveal the results of that revolution to the world. The new Center for Sustainable Landscapes building, which opens in June behind and connected to Phipps’s extant campus, will house the organization’s education and research facilities, as well as its administrative offices. Its green roof will include an atrium with a permaculture garden for educational and aesthetic use by the public, and for raising fruits and vegetables for use in the café. But perhaps its most interesting features aren’t the scores of employees it will house or thousands of students it will teach, but what the center will not do: utilize outside energy to heat, cool or power the building; utilize outside water; add anything to Pittsburgh’s sewage system.

The Center for Sustainable Landscapes is on its way to being one of the greenest buildings on Earth—one of the first finished projects to have accepted the Living Building Challenge, a rating that goes far beyond LEED requirements and calls for buildings that succeed in net-zero energy and water usage, and sustainability in design and construction, while maintaining an aesthetic beauty. (The finished project won’t be certified until it has operated successfully for a year.) But it’s not called the Living Building Challenge for nothing; the road may be sustainable, but it’s also hard.

“This is a first,” Piacentini said. “A lot of the products aren’t out there, and you’ve got to pay someone to do brand-new research” on how to make this specific building work. “But the next person who builds one can use our experience—and the ones after them. And it’s just what makes sense for us. This building is making sense out of everything that Phipps does.”

Behind Phipps Conservatory’s main buildings—the Welcome Center, the Conservatory, the greenhouses and gardens—a steep slope drops down toward the forgotten back end of South Oakland. Slotted into the alcove of this slope, hugging its curves, the Center for Sustainable Landscapes sits like a hidden city. With winding paths and a bridge connecting it to Phipps’s extant campus, the center is framed by a lagoon—necessary for its own water treatment—and science-fiction-like banks of solar panels. Just to the north sit the center’s wind turbines. In its unfinished state this March, the center’s underground tanks sat exposed, waiting to collect all of the rainwater from Phipps’s parking areas.

The Living Building Challenge is based on seven “petals”—site, water, energy, health, materials, equity and, just as important, beauty. Each petal holds its own set of challenges, and many of them are more problematic for the center’s mixed public access and administrative-office usages. There’s been very little precedent to fall back on, and the Center for Sustainable Landscapes has been forged largely of new ideas grown locally. But the ideas it is based on go back a bit further.

In the mid-1990s, Jason McLennan formed a question. The Seattle architect was already interested, and influential, in the green-building movement. But even as the LEED movement was picking up steam (the first certification program launched in 1998), McLennan was bothered by its fatal flaw.

“How do we move from creating buildings that are ‘less bad’ for the environment, to buildings that are actually ‘good’?” McLennan said. “Philosophically, as an idea and a name, [the Living Building Challenge] actually has been around longer than LEED. But the certification wasn’t launched until 2006. By then, the market was ready, because LEED had changed the discussion. But even [in the 1990s], in terms of performance of built environments, we knew that even LEED Platinum was nowhere close to where we could or should be.”

By the time Living Building certification launched in 2006, Phipps was thoroughly engaged in the conversation LEED had sparked. One year earlier, Phipps had opened its LEED-certified Welcome Center—phase one of a three-stage overhaul of the institution’s facilities. But by the fall of 2006, when Piacentini heard about McLennan’s International Living Future Institute’s brand-new challenge to create a “living” building, the Phipps director was leaning in a new direction that matched the challenge nicely. That fall, Piacentini arrived at a green buildings conference with an armful of design ideas for the third phase of Phipps’s new campus—a complete integration of sustainable ideas into the physical and philosophical framework of the institution.

“We were already thinking about a lot of the things that were in this new challenge,” Piacentini said. “It’s all about relationships—between the buildings, with the environment, within the community.”

Within months of hearing about the Living Building Challenge, Piacentini took the idea to his board of directors. He was given permission to ignore the stop signs inherent in the mostly used $36.6 million that the three phases of new construction had originally been budgeted, and accept the challenge to become one of the world’s first living buildings.

Response from the foundation community was immediate and overwhelmingly positive. Piacentini’s original plan had been to press pause on phase three of the capital plan—the Center for Sustainable Landscapes—before it had even begun. “But some of the foundation people came through when we opened the Tropical Rainforest Conservancy,” Piacentini said, “and a few made the mistake of asking me ‘What’s next?’ Every single one of them told me, ‘You can’t wait—you’ve got to do this now.’ ”

A living building isn’t simply a matter of throwing money at a construction team. To date, only three projects worldwide have received certification as living buildings: a research and education facility in Missouri; a wastewater treatment facility turned educational center in Upstate New York; and a laboratory in Hawaii. And though there are around 100 projects in some phase of design or construction registered as participating in the challenge, it is obviously a miniscule percentage of the construction world.

One of the biggest challenges in the design and construction of a structure along the living-building guidelines is the Red List—materials that are entirely barred from use in the creation of the building. Just a few environmentally damaging or otherwise non-sustainable, yet remarkably common, products unavailable to living building designers are PVC, formaldehyde, and some of the most common flame retardants.

The job of overseeing the Center for Sustainable Landscapes’s design and erection has fallen to Chris Minnerly, principal in charge of the project and an architect with Pittsburgh-based firm The Design Alliance.

“Many of the building practices are just standard practices but pushed farther, and never given up on,” Minnerly said. “The trailblazing is in the Red List materials—architects and manufacturers have to respond to that; we have to do a lot of brainstorming and vetting to be sure that what we’re getting is compliant. But manufacturers are responding more quickly than in the past. LEED set the bar higher, and manufacturers have learned they have to respond to that.”

A sense of flexibility and trailblazing is a big part of why Minnerly and his firm were awarded the tough job of building the center. As he points out, when the group presented its plan to Phipps, it was a fairly simple thing.

“We knew there’d be a lot of ways to present what some of the solutions might be, and we expect clients want to hear that, and it was hard to resist doing that, but we did,” he said. “We told them, ‘It’s an integrative design process—we need to hear and talk to you, and we need all the consultants [in place] before we can really move forward.’ ”

Another key for Phipps is that Minnerly and The Design Alliance are both Pittsburgh-based.

At the start, the Center for Sustainable Landscapes was seen as a community project. If Pittsburgh was going to have one of the world’s greenest buildings, it should be made by Pittsburgh. From the beginning, Phipps involved thinkers from Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh’s Green Buildings Alliance in sessions regarding the design and construction of the center. And that is having what McLennan sees as a rather desirable effect.

“The Phipps project is already serving as an innovation starter,” McLennan said. “There are two other registered [Living Building Challenge] projects in Pittsburgh now, and Phipps played an instrumental role in making that happen—the Frick Environmental Center [in Frick Park] and the Schwartz Living Market [on the South Side]. The Phipps’s mandate is to educate, and that makes them a powerful first adopter for the challenge in the Pittsburgh region, and to push out the lessons they’ve learned.”

It’s among several reasons that the International Living Future Institute has chosen the center as the first subject in a series of case-study books to be written about challenge projects. Because the Center for Sustainable Landscapes is its own subject matter: A building that provides a focal point for sustainability in Pittsburgh, and that sets a high bar for future thinking about our urban landscape and the integration of our built environment—and, indeed, our citizens’ lives—within the worldwide milieu of the 21st century.

“I’m not from Pittsburgh originally, but obviously I fell in love with it,” Piacentini said. “I look at the people, the work ethic, the history, and the talent and future of the region. Look at Pittsburgh 150 years ago, when the city was a leader in the industrial revolution. This building helps prove that we have the potential to lead the next industrial revolution, too—the green industrial revolution.