A Tour of the World’s Crumbling Democracies

“Around the world, radicalization is making coalition and consensus much harder” —Gideon Rachman in the Financial Times

Last week I discussed the abdication of the political middle in the U.S. in favor of radical leftist, rightist and populist ideas. Instead of (as in the past) fringe ideas playing the role of informing public debate and possibly (though very rarely) becoming mainstream, all the U.S. has today is fringe ideas—the mainstream has abdicated.

I also pointed out that this troubling situation can’t be blamed entirely on the Trump phenomenon, because “the abdication of the middle” is a global phenomenon. Let’s do a quick survey of this effect by looking at the 10 largest countries ranked by GDP (after the U.S.).

First, though, let’s note that we are only concerned with the health of the world’s democracies, not with whatever is going on in autocratic societies. The hell with them.

Japan. After the U.S. and its $21.5 trillion GDP, it’s a long way down to the next democracy, Japan, with annual GDP of $5.2 trillion. From the perspective of the U.S., Japan can seem like a polite, consensus-driven society in which everyone strives together for the public good and doesn’t waste time on radical ideas.

Actually, that’s not the case at all. It’s just that the Japanese have no choice but to make nice: they’ve been under the American thumb for 75 years.

Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, the U.S. occupied the country, dismantled the Imperial Army and imposed Western-style democracy and other Western liberal institutions. Article 9 of the (U.S.-imposed) Japanese Constitution actually prohibits Japan from going to war against any other country.

The U.S. still has roughly 50,000 American troops scattered among 23 U.S. bases in Japan, and the Japanese put up with this not because they are polite but because they are terrified of China. With no army of its own—only the Japan Self-Defense Force which, while not unformidable, is no match for China—Japan is dependent on the U.S. for its continued existence.

As a result, far from fractionalizing into parties with fringe ideas, one political party (the Liberal Democratic Party) has governed Japan since the end of World War II except for brief periods during 1993–1996 and 2009–2012.

What are we to make of this? What I make of it is that Japan in 2019 is exactly like the Western democracies were in the twentieth century, before we encountered the short-memory problem. I.e., Japan desperately needs to stay stable and mainstream because otherwise the U.S. will abandon it and China will gobble it up. The Japanese don’t need to worry about having short memories because all they have to do is glance to the west across the East China Sea and there is Shanghai staring back at them, a mere 540 miles away.

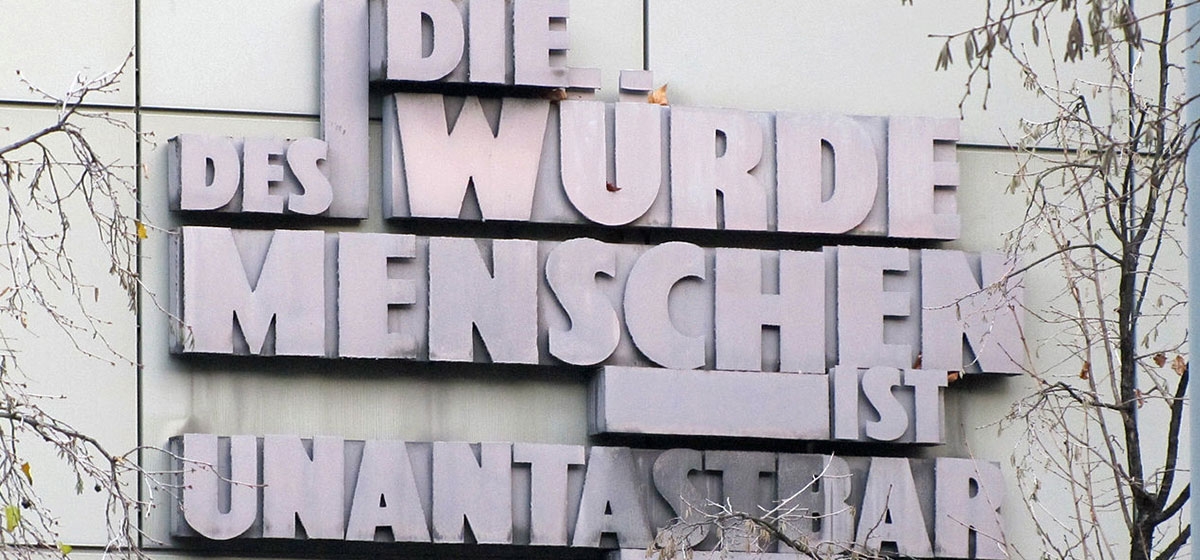

Germany. Germany, with GDP of $3.9 trillion, is well behind Japan in terms of economic clout, but it is in some ways the poster child for a democracy that is slowly fracturing into incoherence.

It may not seem that Germany is falling apart because Mother Merkel has been in office forever. At last count she has outlasted four French presidents, five British prime ministers, and seven Italian prime ministers (so far). But “après elle, le deluge.”

Germany’s post-war history is similar to Japan’s. The U.S. occupied the country, dismantled the Wehrmacht and imposed Western-style democracy and other Western liberal institutions that hadn’t existed in Germany since the demise of Weimar.

After that, for decades Germany was governed by center-right and center-left governments—remember Konrad Adenaeur and Willy Brandt? Between them, these centrist parties would routinely garner 75 percent of the vote.

Then the Iron Curtain disappeared, East Germany was reunited with West Germany, and once more Germany was, by far, the largest and most powerful country in Europe. NATO, it has been said (by British General Hasting Ismay, NATO’s first Secretary General), was launched “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” But the Germans were now up again.

Still, for a time it seemed as though post-war Europe had created the best of all possible worlds. The Continent was at peace, it was increasingly affluent, and its people adhered strongly to all the best liberal ideals. It was “the end of history.”

Except that it wasn’t. The collapse of the Soviet Union and its vassal states in East Europe meant that no one in Europe need fear the Soviet Bear any more and, by extension, no longer needed NATO or U.S. protection.

The Germans were suddenly free to indulge themselves in long pent-up gripes—former East German gripes against the dominant former West Germans; gripes against the sea of immigrants suddenly coming into the country (having been invited by that former East German turncoat, Angela Merkel); gripes against the ECB; gripes against the rest of the EU, who are viewed as a bunch of losers constantly in need of bailing out by Germany; gripes against an untethered global elite.

As a result, the two formerly dominant political parties in Germany are now lucky to get 25 percent of the vote (each), while far right, far left, radically green, and anti-immigrant parties control more and more of the vote. The German middle is slowly-but-certainly abdicating.

India. India (GDP of $2.9 trillion) has the good fortune not to have to worry about fringe ideas and fringe politics because that is all India has. At last count there were some 2,546 registered political parties in India, including eight national parties and 52 state parties. India has a charming practice of allowing individual politicians to establish their own parties—of one.

It’s true that at the national level, Indian politics has been dominated by the center-left Indian National Congress, or INC and, especially more recently, by the center-right party of Narenda Modi, the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP. But that’s pretty much meaningless because fringe parties control most of the states and towns, making India essentially ungovernable.

Its huge population notwithstanding (India is only 75 million people smaller than China, and will surpass China within a few years), India will never become a geopolitical power or threaten to eclipse the U.S. or China economically because of this fractionalization. India, in fact, is a stark example of where we’re all headed.

Next week we’ll continue our weary tour of the world’s crumbling democracies.