A Sailing Odyssey, Part II: Peril on the Seas

It is said that no two trips to the North Channel are ever the same. With a maiden voyage behind me, though, I felt confident about my second trip, which I would undertake with three college classmates, all 60 years old.

I put the boat in the water early, eager to push the engine a little as a precaution before the trip. It passed the first test. Then, on the Saturday four days before my friends’ arrival, I tested it again, running it for an hour in the bay before opening up the throttle. A minute later, a squeaky alarm sounded, mystifying me until thick, black smoke billowed from the cabin. I shut off the engine and peered through the smoke below for fire. Finding none, I tried unfurling the big genoa jib (the genny) but the mechanism jammed.

And when I then tried to raise the mainsail, a rigging mistake when it was launched prevented the main from rising more than halfway up the mast. It was enough to sail, but barely. As I limped back to the marina, I looked like a shipwreck, half-rigged and leaking black smoke. Worse than that debacle, however, was that the marina wouldn’t reopen until Monday — two days before the guys arrived. If the engine was dead, the trip was off, and no other boats were available for charter. Pre-trip anxiety, it seemed, was simply unavoidable.

On Monday, it turned out the “V-belt” had come loose causing the engine to overheat. It was an easy fix. And at 3 p.m. on Wednesday Aug. 3, my pals arrived: Dave Guenther, a law professor from Ann Arbor, Geoff Catlett, a retired Army colonel from Asheville, and Jeff Bell, a college football teammate and newly retired CEO from Seattle. Four big personalities in a 27-foot boat would be its own test. But as we stowed the provisions, Catlett’s military experience paid off immediately, and the little craft’s interior seemed miraculously spacious.

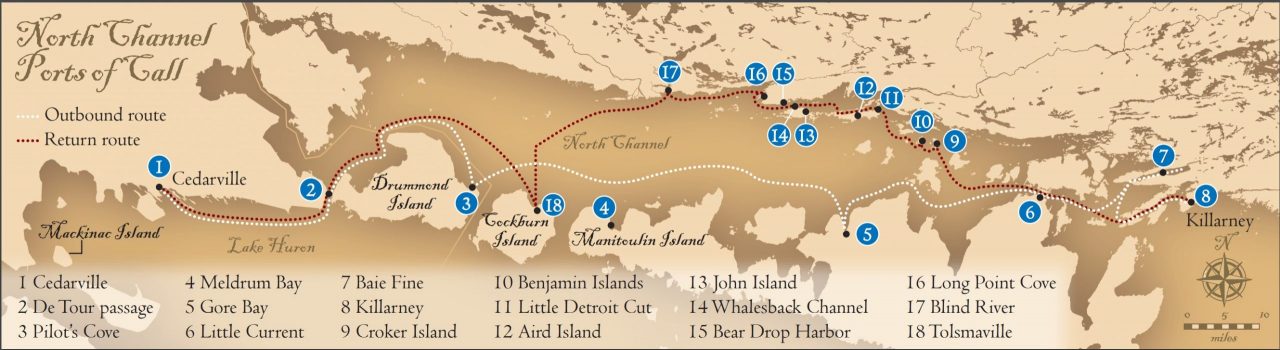

We cast off early the next morning and chugged quietly through the windless, glassy water, saying goodbye to our familiar islands and entering the vast blue of Lake Huron. Spirits were high as the wind rose and we unfurled the genny, doubling our speed. For this trip, I wanted to make it far beyond where my sons and I had gone, all the way to Killarney at the North Channel’s far end 150 miles away. To do it, I told the guys, we had to push hard the first three days, making 50 miles a day. We’d be rewarded after that with an easy sail back, or so I thought.

The first leg was 25 miles east on the open lake to DeTour passage with a favorable north wind. We put up both sails — the main and the genny — and made DeTour around noon, rounding the 83-foot lighthouse, then turning north, passing giant freighters and all manner of boats as we sailed along the west coast of Drummond Island. By the time we finally entered the vast North Channel, we were the only boat in sight. My friends’ sailing experience was minimal, but they quickly learned their way around the boat and the various jobs. Each took turns at the helm that day, but spelling me at the wheel fell most naturally to Bell, and he took to it with pleasure and pride. Guenther had agreed to be cook under the stipulation that someone else do dishes. And Catlett, whom I later dubbed the MVP, made everything work smoothly, cleaning, stowing and providing good humor.

At about 6 p.m., with 50 miles behind us, we reached Pilot’s Cove, so named because navigating the narrow, rocky entrance takes skill. As we slowly motored in and made the hairpin turn north, Bell stood on the bow, poised to point to any rocks that threatened our keel four feet below the water’s surface. The horseshoe-shaped cove — 200 feet long by 50 feet wide — was rimmed by a wall of loose rock on the western, weather side and by forest to the north and east. We dropped anchor in the clear, 20-foot water and broke out the Scotch. After a refreshing swim, we complimented the chef for our first meal aboard, a spicy rice and bean concoction. Keeping an eye on us 60 feet away, a beaver made repeated trips across the quiet water at sunset. We had escaped to a different world.

Our next destination was Gore Bay 50 miles east. We’d first pass the 66-square-mile Cockburn Island (pronounced Coe-burn), home to just 200 summer residents and one year-rounder. Then came Manitoulin Island, the largest fresh-water island in the world — 1,100-square-miles that the Ojibwa tribe consider sacred spirit land. Tacking into a headwind, the hours crawled by. It was hot and we discussed everything — movies, stocks, and the shrinking of America’s marketplace of ideas. I described Gore Bay as a lively port town with a bustling marina, a variety of restaurants, a brewery, a thriving little main street and a summer theater program, where we’d taken in a show after dinner three years ago.

When we finally arrived, I’d been steering for 12 hours and was tired and sore. We passed Customs via a painless telephone call featuring the Colonel saying “Yes, Ma’am” and “No, Ma’am.” The charming town I’d promised, however, had been decimated by Canada’s two-year border closure and the loss of American mariner revenue. We hustled to the last open restaurant, which closed its doors at 8 p.m., quickly downing some beers and devouring a meal. The town we explored after dinner was a shadow of what it had been, and we headed back to the half-empty marina.

Early the next morning we set off for the world’s largest freshwater fjord — Baie Fine (pronounced Bay Finn) — 35 miles away. In another 10 miles, we’d be farther east than I’d ever been, passing through Little Current and the bridge connecting Manitoulin with the Canadian mainland. The bridge swings open on the hour, allowing boats through the narrow channel, and we made haste to get there by noon. With a steady southwest wind, it was the best sailing of the trip, and we ripped along at seven miles an hour, passing other sailors with pride as we headed east. After just missing the noon bridge opening, we stopped at Little Current to replenish, refuel and explore the bustling town of 1,200. At 1 p.m. sharp, we motored by the opened bridge, unfurled the genny and sailed into the big waters of the eastern North Channel. Bell took the helm for long periods as we tore across the seascape, taking in new sights and the occasional outpost on otherwise uninhabited islands in a vast expanse of open water.

We made the entrance to Baie Fine by 4 p.m., happy to escape the wind and waves and enter the protected waters of the narrow 10-mile fjord. We passed the Okeechobee Lodge, now in private hands and off limits, and continued on, admiring the fjord’s magnificent granite cliffs and the craggy pines clinging to them. It looked like the perfect place to fish, and I suggested the guys put some line on the three new rods I’d bought and troll as we motored slowly along. At the fjord’s far end, I mentioned, there was a shallow passage where we could anchor the boat and take the motorized dinghy up to “The Pool,” a place of fabled beauty and solitude.

“Well, if no one’s going to set up the rods, I’ll do it.” I said in joking manner and asked Bell to steer. As I put line on the empty reels, he asked me if he should follow the dotted line on the GPS. In my experience, the dotted line showed previous routes my sons and I had taken, and since we’d never been there before, I told him not to pay attention to it and just sail where the deep water was. I was nearly finished with the first reel, when a tremendous “Boom! Ba-Boom-Boom!” violently jolted and heaved up our heavy boat.

“Oh My God!” Bell yelled in the chaos. I knew instantly we were hitting rocks and lunged for the controls, shifting to neutral to protect the propeller. We slammed to a sudden stop. Just ahead of us a ledge of red-brown granite rose a foot above the water. We were grounded. Lodged on a reef. In remote waters a long, long way from home.

The crash had broken some things and thrown others to the cabin floor. My friends were shocked speechless, fearing we might sink. A quick assessment and 55 years of driving boats told me otherwise. We hadn’t been going that fast and, cracked or not, our keel was three tons of lead built to take a blow.

“We’re okay,” I said in an intentionally calm voice. “Let’s get everyone up on the bow. That’ll lift our stern, and I’ll see if we can reverse off the rocks.” No luck. I brought the guys back. We doublechecked the bilge. No water was coming in. It was time to think.

“Colonel, hand me that fishing rod, will you?” The impact had broken all three rods, but one was still long enough to gauge the water depth to see if we could hop in and push the boat off. Just then, a boat hailed us, asking if we needed help. I thanked them and said I wasn’t sure yet. For a moment, we seemed to slowly shift in the current. I got the guys back on the bow and reversed the engine again for a second. We moved slightly and seemed to turn. “Okay guys, come on back to the cockpit — we’re going to try moving forward.” We did move, maybe a foot, and the stern swung out a little more. Enough, I hoped, to escape the rock behind us. It was. I put it in reverse, then neutral, repeating the pattern, and slowly we backed into deeper water.

Throughout the ordeal, parallel thoughts raced through my mind. “How the hell could he steer us onto the rocks right in front of us?” Technically, I realized, the responsibility was mine. Bell would be feeling terrible about it, and I’d say it was my fault. But as I considered the episode more, I realized it was more than “technically” my fault. I was the skipper. I’d asked Bell to take over and he had. He’d even asked me about the dotted line, which now obviously marked the best route. The fact that he was focused on the GPS and not looking at the water ahead of him was purely a matter of experience, and I was the only one who had any. Simple as that. As we got underway again, I told the guys it was my fault and apologized. When someone started to disagree, I reiterated why it was my fault, period.

The crisis passed, but the effects lingered. Bell sat on the bow for 15 minutes. The Colonel went into the cabin and sat quietly. Guenther and I exchanged looks. He whispered that he thought Catlett might be experiencing PTSD. We’d never seen him like this before, and Catlett later confirmed it: The crash reminded him of when a bomb blew up under his military vehicle.

Slowly, everyone returned to themselves and we marveled at the fjord’s extraordinary beauty. We travelled its length and decided that instead of exploring “The Pool” in the dinghy, we’d find a suitable anchorage and relax for the evening. The most ideal coves already held several boats and Guenther, admitting an anti-social streak, suggested finding one without anyone else. And so we did, settling on an inlet that was both out of the wind and suitably deep. We anchored and relaxed. Bell took a long swim, exploring the granite boulders, and I fished off the bow as Guenther made dinner. Later, as darkness fell, the wind unexpectedly shifted and was blowing right at us. Despite having both anchors out, they appeared to be dragging, and the wind seemed to be slowly pushing us toward the rocky back of the cove. We hadn’t moved much, but enough to be disconcerting, and the problem defied an obvious solution. Going to sleep was out. The wind could pick up and push us onto the rocks. Pulling anchor and finding another spot wasn’t good either. It was 10 p.m., too dark to avoid rocks in another anchorage. And I didn’t relish leaving the fjord in the dark for our next destination.

“When we face a situation like this in the Army,” Colonel Catlett said, “We delay deciding until the facts become clearer. We take three-hour shifts, with some on watch while others sleep.” It was the best solution, and I said Bell and I would sleep first until 1 a.m. and that they should wake us if anything changed significantly. I fell asleep instantly and awoke at 12:30. When I reached the cockpit, the wind had died completely, and we hadn’t moved. The danger had passed.

The next day dawned windless. We set off for Killarney early to beat the imminent rain and motored into a vast expanse of gray — patchy gray fog, a low gray sky, and glassy, gray water, dotted by flecks of foam. Guenther said it looked like we were sailing through a gray Rothko painting. It was eerily quiet and beautiful, a peaceful tonic to the previous day’s stress. And in that silence, we heard a long, mournful call from somewhere off to the left. The call was so strong that I first wondered if it was a wolf. No, it was a loon, strong and unforgettable, and just as I recognized it, its mate returned the call. The next day, we sailed within 15 feet of one in the water, close enough to see its red eye and beautiful blend of black and white feathers. It was a highlight of the trip, the closest any of us would ever come to that solitary bird. And we felt we were way out beyond the edge of the normal world.

(Coming next Thursday, Part III: Conclusion)