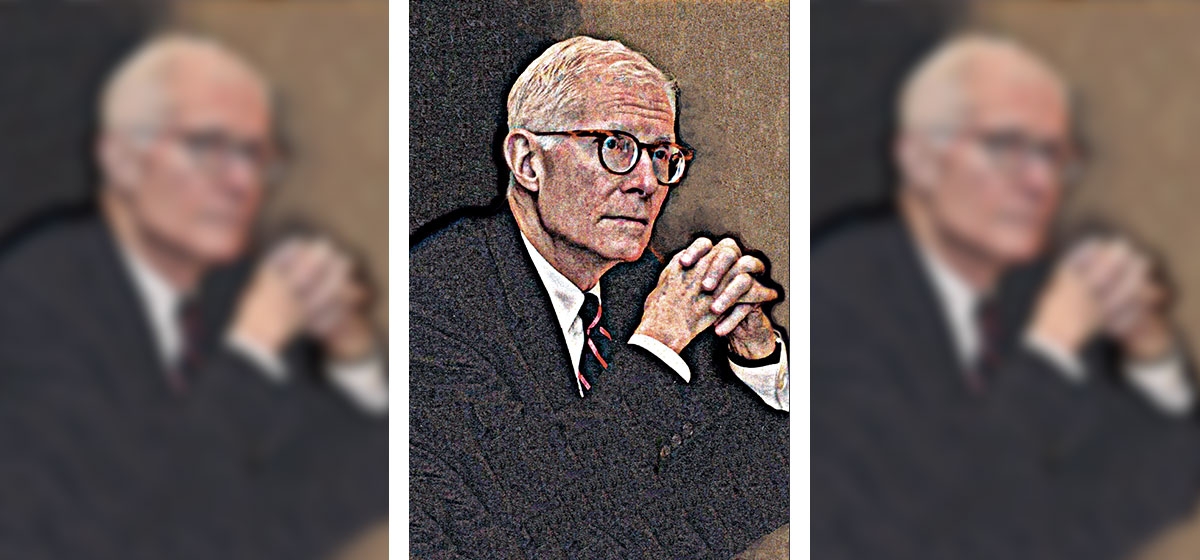

At a civic event 11 years ago, I saw an unusually dapper fellow—navy pinstripe suit, rep tie and perfectly combed white hair. The fact is, I thought he was someone else. I went over and introduced myself, and he said, “Bill Dietrich.” The name meant nothing to me. But after chatting for a minute or two, it was clear that he was a man of consequence—smart, decisive, and thoughtful.

Over the next several years we talked at events and parties. I got to know him well enough that when I was starting this magazine, I asked Bill to lunch. When I told him what I was up to and asked if he’d like to invest, he was nice enough to partially suppress a laugh. “Magazines are not my kind of investment.” The lunch then limped along in obligatory fashion until a few minutes later, Bill said, “Maybe I could help you in another way; maybe I could write for the magazine.” “Oh, that would be great,” I said, thinking to myself that the last thing I needed was the pontifications of a steel magnate. Months passed and after our first issue came out, I got a call from Bill about writing. He was always one to follow up. And so began a friendship that involved my editing and helping him with his writing—he didn’t need much help—and his counseling and helping me on business. He wrote in every issue of the magazine except the first and this issue. And his pieces, which have been collected into a book called “Eminent Pittsburghers,” were the most consistently popular stories we published.

He never accepted payment for the stories, and I never complained about that. But at one of our quarterly lunches at his usual table at the Duquesne Club, Bill said, “You know, I put in a lot of time on these stories, and I figured out that, at my hourly rate in the investment world, each of these stories is worth about $118,000.” From then on, he told people he was my most expensive unpaid writer. At that same lunch, he rapped his knuckles on the table, which always indicated the end of the meeting. I had the temerity, however, to ask his advice on one more business matter. “Christ! You’ve already got me unpaid—now you’ve got me on unpaid overtime!”

Almost exactly a year ago, I was at a large holiday party in early December. I had just put an issue of the magazine to bed and was feeling good—carefree even. Then, someone came up to me and said, “I’m sorry about Bill Dietrich.” “What about Bill?” I asked. I was told that he had cancer and was in hospice care. It was a shock to me and to everyone who knew him. Partially because he was such a healthy person—a model of fitness, diet, discipline and will—and partially because he was the epitome of vitality.

I went to see him at St. Barnabas. He was thin and weak. He had hoped to have the time to build the Dietrich Charitable Trusts to $1 billion, but $500 million would have to do. He expected to live just a few months and said his only regret was that he wouldn’t be able to finish his book on China. “It would have been my best.” His determination, however, returned. He left the hospice and began living again, battling the clock, turning a few months into almost a year, and using what energy he had to work on the book.

In early September, on the occasion of his $265 million gift to Carnegie Mellon, Bill gave a speech, which was, in my opinion, his finest hour. It was a hot day, and he leaned on the podium as he spoke. Filled with intelligence, humor and self-deprecation, the speech could be distilled to a single line, in which he attributed his success in life to the love he received from his parents, and particularly his mother when he was young. “Underpinning all our achievements and accomplishments is a simple sense of being loved. It’s that feeling of security that allows us to take the risk, dream the dream and dare to live life with the courage that is forged by nurturing and abiding care.”

Every few days in the month between the CMU event and Bill’s death, another of his historic gifts was announced. The last time I spoke with Bill was a week before he died. He wanted some final edits to the “What Do I Know” feature in this issue. We went through them, and then I congratulated him on recent events, asking him, tongue in cheek, if he was continuing his media tour. His voice was weak, but he quipped: “Dietrich died of gall bladder cancer, didn’t he? Nope, sumbitch died of overexposure to the media.”

A few weeks after Bill died, I was at a meeting at Carnegie Mellon, where there was some informal conversation about people and their favorite books. I was asked what book I would pick to associate with Bill, who had quite a library. After a moment I said, “The one on China—the book he didn’t get to finish.”

I picked it because that was Bill. His next endeavor was always going to be his best. Even at 73, he believed in self-improvement and in the future. It was inevitable that he’d leave an unfinished project. When he was at Princeton, he realized that wealth was society’s proof of success. He didn’t come from money, but he vowed, “I’ll show the bastards.” And he did. But money wasn’t his main goal. His goal was to accept a challenge and to succeed. Life was a gift of time, and time a challenge to fill with daring and accomplishment. He set his sights on greatness, and by nearly any measure, he achieved it.

At the end of the many stories he wrote for this magazine on the lives of Carnegie, Mellon, Heinz, Westinghouse and many others, Bill typically closed with a discussion comparing the qualities of his subject with other great Pittsburghers and with a comment on legacy.

And so, in this column, which, like Bill’s stories, is twice as long as the space we’d intended to give it, I’ll close in similar fashion.

William S. Dietrich II will go down in Pittsburgh history as one of the great philanthropists and in the league of those about whom he wrote. The $500 million will grow and be a lasting legacy, flourishing all around us in the life and future of the great institutions of our city.

But the way he lived is another part of his legacy, and in that he was unlike many of the great Pittsburgh titans. Bill never reached a high point followed by years of decline and fallowness; his was a progression ever onward, ever upward.

He was a self-made steel tycoon who sold his company, Dietrich Industries in 1996 for $146 million. He became an investor extraordinaire, more than tripling the money from the sale of his company during the last 15 turbulent years. He was a scholar, who earned a Ph.D. in political science at Pitt in his forties. He was an award-winning journalist and author with two books and nearly a third to his credit. And he was a great philanthropist.

In the final tally, Bill was unique among the storied greats of Pittsburgh history in the talents he possessed and the “luck and pluck” with which he gave them full expression.