A Creepy Mill Town

Calynn Lechner isn’t sure what’s looking back at her. The clay face she’s sculpting has a beak like a turtle and lobster-ish whiskers. When she’s done, the skin will look gelatinous, like a jellyfish’s. “It’s a smorgasbord of everything,” says Lechner, 23, her tattooed arm moving slowly as she uses a scalpel-like tool to carve details into its face.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”147″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

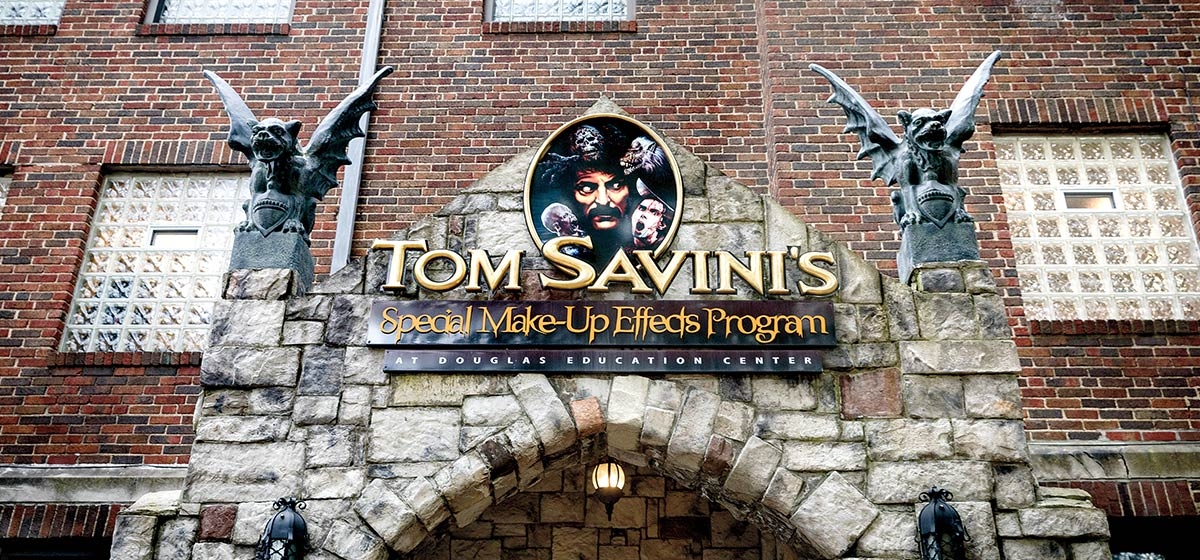

Since she enrolled in the Tom Savini’s Special Make-Up Effects Program at the Douglas Education Center, she can’t look at a creature without scanning its anatomy for bits that could be borrowed for a movie monster. “I pet my dogs and I notice their muscles,” Lechner says.

She’s surrounded by classmates, all working on their own clay heads. There’s a rat, an alien, a haggard witch, even a chicken. This is an animatronics class and these creatures will move. The eyes and mouth of Lechner’s amorphous sea creature will pop open.

Two years ago, Lechner was earning a degree in elementary education at Austin Community College. After graduation, she couldn’t picture herself in a classroom—or in any job that kept her in the same room day after day. In Austin, she tended bar and took art classes. She saw former students of the Savini program on “Face Off,” the reality show on the Syfy network that pits prosthetic makeup artists against each other in an “American Idol”-style competition. She could do that, she thought.

It was a “challenge,” she says, convincing her boyfriend to move from Austin—one of America’s most culturally lively cities—to the Douglas Education Center’s home of Monessen, an economically battered town 30 miles south of Pittsburgh where about half the buildings sit unoccupied. “I think he was curious and he wanted to support me,” Lechner says. Her boyfriend, who also has an education degree, found a job as a paraprofessional at the local school district.

They rent the bottom floor of a house they share with housemates. They don’t go out much on weekends. “I stay in with Netflix and sculpt,” Lechner says. “Sculpting parties are big here.”

The Douglas Education Center has survived—and expanded— through the desolation that has sunk the rest of Monessen by attracting students with Hollywood dreams to a distinctly unglamorous location. When it implemented the special effects makeup program in 1999, the 117-year-old vocational school had around 100 students, according to Douglas officials. It has 334 in the most recent survey from Peterson’s College Data. While it still offers some more typical programs—for truck driving and medical billing and such—the big driver has been the special effects makeup program, in which 150 students are enrolled. Where it was once contained in a single building, Douglas has spread to 10, absorbing once-derelict property downtown, sometimes buying structures fallen into disrepair from the town for as little as $1.

In the decades since the steel mills closed, Monessen’s 1960 population of 18,424 has been whittled down to 7,720. The most recent town-sponsored survey found that 57 percent of its buildings are essentially owned by the town, put into receivership for code violations, back taxes, blight or other issues that creep up when a town is abandoned. Douglas’ campus snakes through this landscape of boarded-up buildings and aged brick. The school is like the lone survivor of an economic horror story, one beyond the ghoulish imaginations of its students.

For most of its history, Douglas trained secretaries and salesmen, making some white-collar positions available to people without a four-year degree. Jeffrey Imbrescia, an accountant by trade who purchased the school in 1989, says it had to go beyond the typical because of population decline in the area.

“There weren’t enough people here to support the center,” says Imbrescia, “so we had to look into programs that would attract students from all over the world.”

In the late 1990s, an acquaintance from the Art Institute of Pittsburgh suggested he meet with Tom Savini, a Pittsburgh native who rose to fame in the B-movie cultural sphere first through his work on George Romero’s zombie movies. In 2008, the school added a filmmaking program named for and made with input from Romero, a natural complement to the Savini program. Currently, 16 students are enrolled in it. Imbrescia said enlisting known names for their “expertise was a way to gain instant credibility.”

Students leave the programs after two years with specialized business associate’s degrees and, the heads of the program say, the grit and skills needed for the grueling work of a film crew.

They have made Douglas one of two significant economic presences in town, on par with the ArcelorMittal coke plant, the last remnant of industry whose smoke had acted as a solitary sign of life in Monessen.

“I think without Douglas and the coke plant, the town would shut down,” says City Councilman Ed Lea. “There would be no tax base.”

In addition to Douglas’ expanding presence, Boss Development Inc., a property company also owned by Imbrescia, has been buying up homes throughout town, gobbling up 20 since 2000 according to county property records, and primarily renting them to students. This places horror movie fanatics next door to Monessen’s longtime holdouts. The dynamic can get weird.

“I think some of the people, the older people, get the wrong impression of the kids because they have piercings and they have tattoos,” says Mary Jo Smith, the town’s former mayor. “They’re just kids. If you treat them with respect, they treat you back.” Smith, a self-described “old lady,” adds, “I sometimes can’t pay attention to them when they talk because I’m just following the piercings in their nose as they move.”

Douglas is virtually the only agent of change in Monessen. Sitting at a conference table at the school’s new welcome center (a former church it assimilated from the downtown landscape), Imbrescia brags, “We are the town. The police force has let us use equipment [for film shoots]. Building owners have let us use rooftops. Everyone knows us.”

Still, Smith laments that Monessen’s only magnet for new residents is attracting temporary ones, unlikely to stay and build up the tax base and community it’s lacked for decades. “It’s not enough,” she says, “and unfortunately we don’t have the jobs [the students] are looking for.”

Thirty-nine-year-old Jason West of Fort Wayne, Ind., enrolled in the Romero film program, is one of the temporary residents passing through Monessen. After his discharge from the Air Force, West took a job as a machinist in a factory, but the daily grind made him miserable. He saw an ad for Douglas in “Fangoria,” the prominent horror movie magazine.

“Once I had my wife’s full support, I went for it,” West says. “She knew I couldn’t spend the rest of my life in a factory.” (She stayed behind in Indiana.)

Nearing graduation, he’s learned script writing, lighting, editing and even budgeting for film production. West says his “strongest skills are behind the camera.” He adds, “My ultimate goal is to be the DP [director of photography] on a major motion picture.”

Many students enter the film program wanting to become DPs or directors. Such an opportunity won’t be available for all of them, says Robert Tinnell, the program’s director, whose movie writing, producing and directing credits date back to the 1980s.

“There are jobs in social media and reality TV,” he says. “There is this ever-increasing need for content and people get good jobs.” He adds, “There are key grips who make $90,000 a year and have beautiful houses.”

This truth informs the handson approach of Douglas’ film and makeup programs. A little time is dedicated to film history and theory. Most is spent on the rapid acquisition of skills that is typical of an associate’s program. And the ethos synchronizes with the work ethics of Savini and Romero, who contributed to dozens of films in their careers, often with a do-it-yourself attitude.

“You have four-year programs and the students don’t even touch a camera until the third year,” Tinnell says. “Not my kids.”

Students split up into teams a few times before graduation and produce actual films. The program doesn’t exist to create film snobs but crew members able to fill any entry-level film production position.

“You know everything Fellini has ever done?” Tinnell says. “Guess what, no one on [the crew of] ‘Dance Moms’ gives a —.”

The makeup program has a similar outlook. Creative kids inspired by sci-fi and horror movies come, hoping for jobs in Los Angeles “shops,” specialty makeup production companies. The school values their creativity and displays their devil heads and monster statues in buildings. But graduates also have options in other fields, says Jerry Gergely, director of the program.

“We’re not a monster school,” he says. “We encourage people to think beyond that.” Those who don’t make it into the movies could work for Disney- and Universal Studios-style theme parks, haunted houses and even medical prosthetic companies.

Jonny LeStrange (a professional name), originally from Allentown, says he was a misfit in high school and wasn’t sure what he should do after exiting and getting his GED. As a hobby, he created elaborate makeup and face paint designs, often bemusing customers at the mall shoe store where he worked.

He enrolled in the makeup program and is completing his last semester. “The school opens a whole bunch of doors,” he says. “You learn to sculpt, do hair, ventilate wigs.”

Because he doesn’t drive, his education has meant months stranded in Monessen, hoofing to and from Foodland and Dollar General. But LeStrange and his housemates have a place with a large workspace and the lack of distraction allows him to focus.

Lea, the city councilman, says the students are often walled off from the rest of the town. “That’s the one thing I would like [to see change],” he says. “I would like to see the students become more a part of the community and travel outside the school. They are not with the residents and frequenting the local businesses as much.”

Smith says she has concerns that the influx of students is not providing Monessen with the revitalization it needs.

“When Boss takes over a property, they are bringing it up to code, but they are not bringing it up to the level where it will increase property values [in the whole area],” she says. “It’s students, so sometimes they won’t put the garbage out correctly.” It’s not creating the tax base “where we can hire more police officers or ensure basic services,” she says. She doesn’t blame Boss or Imbrescia, but says the town should be more invested in attracting other property owners.

Lou Mavrakis, mayor at the time of this writing, says the city has 400 houses and 25 other buildings in a state of disrepair. “It’s a struggle to find anyone who can take them.” He adds that he’s glad to get any of them back on the tax rolls and secured. “When they’re all boarded up like that, it’s a sign for the druggies and the vandals.”

The landscape is ripe for filmmakers and artists obsessed with horror and sci-fi scenarios. Cody Patterson, a 22-year-old film student, concocted a short film, “Lonesome Highway,” after discovering that there was abandoned roadway that had once been a section of the Pennsylvania Turnpike nearby. It’s a post-apocalyptic story of two brothers avoiding a gang of slavers in a vast no man’s land. (The roadway was put to similar use in a big-budget dystopian thriller, 2009’s “The Road.”)

“I was entering my fourth semester and wanted to get something like that done,” Patterson says. “I wrote it. We set up a shoot schedule.” Six film students worked on it, with a makeup student. They got permission from the land conservatory that owns the deserted thoroughfare.

“I just thought it was perfect,” Patterson says, “and this is the movie that needs to get made here.” He did what do-it-yourself filmmakers and institutions in the Rust Belt have done by necessity for decades: Take what was available and make it into something.