Stand at the top of the angles stairs in the entry to the Squirrel Hill Library, and you are cantilevered out and over Forbes Avenue, beyond the facades of surrounding buildings. The way the building creases and folds here, you can see outside and back in at the same time.

Go past the free-standing elevator shaft, beneath the exposed ducts, and into the library space, and a tent-like canopy of copper rises on a white steel frame to create a comforting sense of shelter that you can feel, a central gathering space in a library that spreads out a selection of smaller spaces for children and teens, as well as regular visitors to inquire, read, work, meet or relax.

Designed by Arthur Lubetz Associates and completed in 2005, this building is the 7,000-square-foot expansion and renovation of an existing structure from 1972. It is useful and welcoming, but, like much of Lubetz’s work, its most prominent features poke at architectural convention in subtle and overt ways.

Lubetz is continually one of Pittsburgh’s most thoughtful and challenging architects, even as he completes, remarkably, a half century of practice. As a student at Carnegie Tech in the 1960s, he was friends with artists Mel Bochner and George Nama, who became prominent artists. Over the years, he has cited art, philosophy, and, more recently, neurobiology as ways to understand architecture, even as he has insisted that buildings must speak clearly to everyday people. “Architecture is a public art and therefore demands of us a language that communicates with this diverse public,” he says.

You can find innovative Lubetz ideas in his earliest works— mansion-to-condo renovations in Shadyside and some understated forays into subsidized housing further afield. In the early 1980s though, he had a pronounced resurgence creating some of the city’s “most unsettling and provocative architecture,” critic Patricia Lowry wrote at the time.

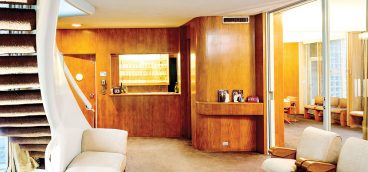

One notable project is his own office at 357 N. Craig St. This pre-existing auto mechanic’s shop was utterly transformed by its conversion into the architect’s studio with additional rentable space. The concrete block building with plenty of salmon-colored stucco walls and teal trim is an exuberant play on basic elements of architecture. Walls stand free beyond any roof covering. A staircase turns upside down and rises to an orphaned, oversized window. Building parts slide past each other in receding layers of space instead of aligning the way you would expect. Inside, the architect’s studio is a double-height space with an off-scale grid of windows in that continuing salmoncolored wall. There is a building within a building, which functions well to house key offices and conference rooms, while continuing the sense of architectural elements at play rather than rest.

It is still one of Pittsburgh’s best buildings of the era, notably more complex than the Abrams House by iconic postmodern architect Robert Venturi. Lubetz’s work perhaps still nips at the heels of the Giovannitti House, Richard Meier’s masterpiece, but it’s still a real part of the conversation. It is “both billboard and sculpture” said Architecture magazine when they wrote about it in 1986. Also in the early 1980s, Lubetz made one of his most strident and outlandish buildings, on Dalzell Place in Squirrel Hill. Lubetz was, as always, influenced by avant-garde art, particularly ideas of artists such as Richard Serra and Gordon Matta-Clark, who brought actions of breaking, slicing, sliding, and tearing to their work. Accordingly, on a pleasant medium-sized builder’s house from around 1910, one in a row of almost-identical structures, the architect designed a huge red slab (now repainted a pinker shade) slicing through the middle of the house and coming out the back. On the interior, a staircase spirals upward through it, and a double-height space enhances the sense of architectural drama. Various holes allow passage from one side of the house to the other. The boldness of the initial idea gives way to greater subtlety. Dalzell Place House clients complained that Post-Gazette critic Donald Miller “did not seem to grasp the underlying complexity and philosophical intent” of key Lubetz works.

Decades later, drama and paradox hold similar sway in Lubetz projects. In pre-construction models, his Glass Lofts on Penn Avenue looked like another project that might be too outlandish to build. The vivid backward tilt of cubic volumes and the adventurous sprawl of stairs and walkways across and up the hill flout convention, to say nothing of the fluorescent shade of green. The persistent idea of architecture acted upon by vivid physical actions still seems valid here. For the Glass Lofts, though, Lubetz has talked about this work in terms of theories of incompletion, a concept he has researched and taught since the 1990s.

Buildings, he and supporting theorists argue, are at least as interesting under construction and demolition as they are in use. Also, importantly, only use and change allow them to reach their real potential. A few sessions of Lubetz’s theory course might help in clarifying his notions of incompletion, but there is no doubt that these energetic and sculptural buildings are meant to defy conventional architecture. “My aim is not to persuade, but to encourage people to think,” he states.

In 2011, Lubetz merged with Manhattan-based Front Studio, a firm founded and run by his former CMU students Yen Ha and Michi Yanagishita. He now practices as a principal of that firm, no longer Arthur Lubetz Associates. Still, his Sharpsburg Library, completed in 2014 (and featured in Pittsburgh Quarterly that year), is as sculptural and vibrant as any of his older works, and it was recently written about with praise in Architects’ Newspaper.

With designs on the boards for locations in Polish Hill, the South Side Slopes and Beechview, as well as an outlandishlooking but very serious proposal for a hotel, apartments and cantilevered convention hall for the Andy Warhol Museum, Lubetz, now Front Studio, is as active and engaging as ever.