Going Back in Time to Ambridge

Growing up in the early ‘80’s as a native-son of a local borough named after a steel-magnate, it’s easy to recall how mill closings affected my hometown. Layoffs were followed by hushed talk of unemployment checks, and later on, businesses shuttered leading to diaspora when folks looked to start fresh elsewhere. In a swath of former factory towns that stretch from Duluth to Baltimore, a sometimes-misguided sense of nostalgic pride emerged, as well as a willingness to establish a new regional identity that’s still evolving in many places.

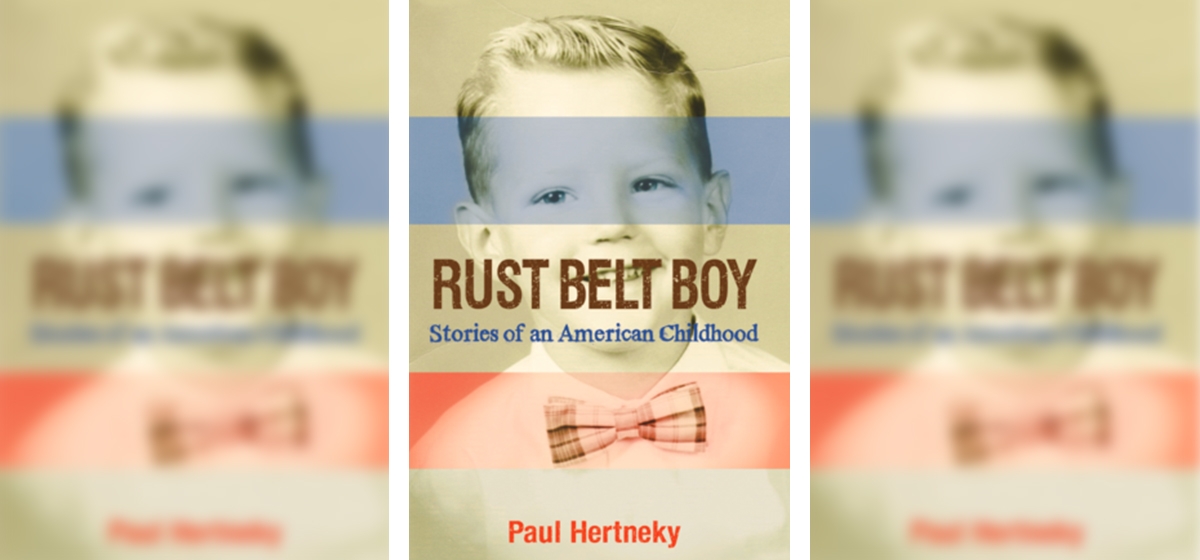

With that in mind, Paul Hertneky’s recent memoir, Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood (Bauhan Publishing), serves as a deftly written prelude to this upheaval, focusing on family and personal growth in the years prior to steel’s big collapse. A baby boomer coming-of-age in the late 1960’s, Hertneky attended the University of Pittsburgh, graduated from the Bennington Writing Seminars and is a faculty member of Chatham University. Now living in New Hampshire, he’s written for the Boston Globe and NPR, among others.

Most important, perhaps, is that he grew up in Ambridge, a former steel-town now best known by some for its “Police-Station” Pizzeria. Indeed, the town, described as a “once-illustrious plateau…[with] its steep hillside neighborhoods, fifteen miles upriver from Pittsburgh” plays as a touchstone for Hertneky, who writes:

“Sons and daughters lucky enough to feel attached to a distinct hometown know it works its way under our skin and into our being. Pluck a hair out of my corpse a hundred years from now and DNA evidence will show that I grew up in Ambridge, one place on Earth, starting in 1955. Biologically, I am tied to it, but that’s just the beginning.”

Indeed, by taking readers into its churches, mills and bars Rust Belt Boy mines historical aspects, personal relationships and physical details, seeking out the idiosyncratic while forgoing cliché.

In a chapter titled, “The Nation’s First Economy,” Hertneky skillfully lays out how his hometown came into being (where a fort once stood) with the June 6, 1824 landing of, “a steamboat named Ploughboy chugging upriver, carrying two hundred Harmony Society members and their self-proclaimed prophet George Rapp. A firebrand and free-thinker, Rapp had been jailed for thinking too-freely about Lutheranism in Germany in the late 1700s. When authorities cut him loose, he told his flock of nearly twelve thousand that he would lead them to religious freedom in America.” As self-sufficient Communists later praised by Marx and Engels, the group also proved to be shrewd businesspeople.

Harmonists came to dominate American silk markets, sold important provisions to those headed West and shipped many goods cross country and worldwide. They’d later provide the Union Army with supplies, help secure a loan to develop Pittsburgh’s water system and owned the land where Drake struck oil in Titusville. In 1902, the Harmonists were bought out by industrialist J.P. Morgan, and steel made by his American Bridge Corp. would anchor some of the nation’s most iconic structures. This historical background delivers a fascinating layer to the extended anecdotes that follow.

Relationships, especially with family, offer another avenue for Hertneky to explore. Born of Eastern-European stock in multi-cultural Ambridge, there’s little conflict in these sections of Rust Belt Boy, which to some may seem idealized. When he writes, “we were loved—by more than our parents, by everyone crammed into those houses, faces I can still see attached to names I can’t remember,” it’s easy to call it sentimental. However, these moments ground the writing and invoke a child’s playful perspective. From watching Gunsmoke with grandparents to hiding underneath a dining room table at gatherings it’s apparent family means everything. It also allows Hertneky to highlight moments of gustatory sensation.

When he adds in the edgy-titled “Moms Who Put Out,” that “Food played a starring role in our lives; all ethnicities had their specialties and everyday meals, and some I could identify the moment I crossed the threshold,” he’s stating an important theme of cultural identity. The run-up to a Friday school lunch in “The Prurient Power of Pierogi,” being enough to make mouths water over “handmade stuffed dumplings, served in butter and onions.” Elsewhere, there’s “the sweet smell of scalded milk” and whiskey, “too penetrating for a summer morning.” He even describes watching the J&L plant spewing pollution while eating McDonald’s as “towering orange, black and white plumes dense as cauliflower.” The physicality Hertneky invokes throughout the big-hearted Rust Belt Boy, makes for a delicious descriptiveness instead of dwelling on the philosophical ramifications of a changing birthplace.