Timeless & Unremembered

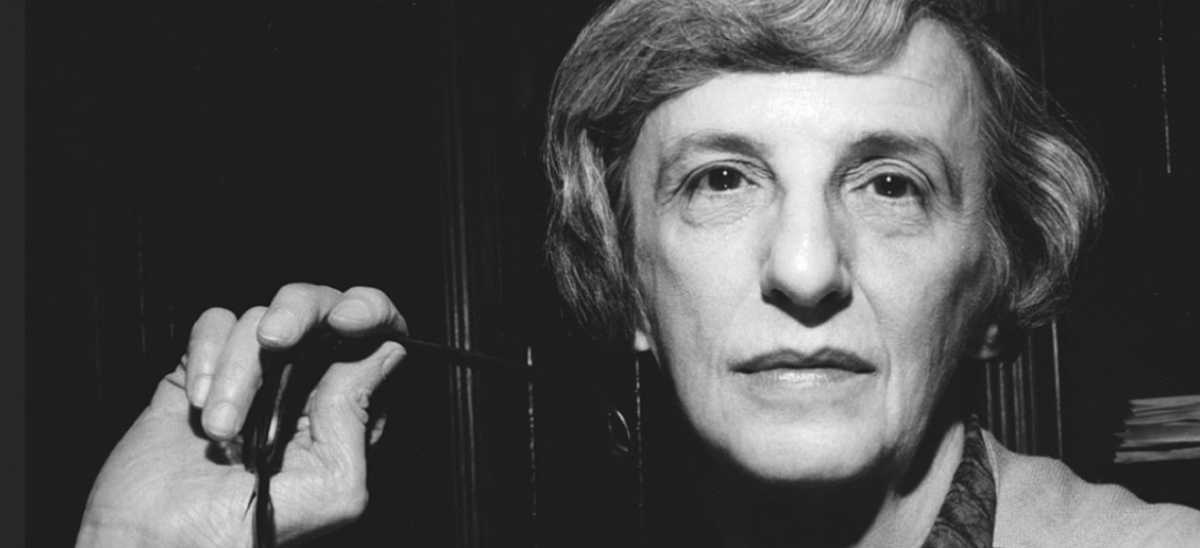

Gladys Schmitt is a wonderful Pittsburgh writer you have probably not read. If so, the time has come for that to change.

“The Collected Stories of Gladys Schmitt,” assembled with care by Carnegie Mellon University Press, presents 20 stories that she published in popular and literary journals, mainly between the early 1930s and late 1950s. Vivid character studies told with easy erudition, grounded in prose shorn of any false note and dappled with laugh-out-loud lines, these stories must be an ideal introduction to her body of work: They’ll set you on the hunt for her nine novels, some of which were best sellers in their day, but are now largely out of print.

Schmitt was a total Pittsburgher. A graduate of Schenley High School, she attended the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University), graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a degree in English and, after a decade in New York at Scholastic magazine, landed at Carnegie Tech (now CMU) in 1942, where she became a beloved teacher and founded the creative writing program in 1968. She was married to her high school sweetheart, Simon Goldfield, who served as her chief reader and critical editor.

According to a 1961 profile in The Pittsburgh Press, they lived well in “a big, English-looking house on Wilkins Avenue” in Squirrel Hill, purchased after her novel “David the King” sold over a million copies. The Press profile was published in the society pages, under the rubric “Portraits of Pittsburgh’s Most Interesting Women,” and noted that “Miss Schmitt does no housework or cooking of any kind” but that the couple entertained constantly and that “the coterie is intellectual.” Her work ethic was epic, by all accounts, as devoted to teaching as writing. “With the exception of occasional business trips to New York, they never leave [Pittsburgh],” the profile reported. “ ‘We haven’t taken a vacation in 12 or 14 years.’ ” She died of a heart attack in 1972 at the age of 63.

I present these biographical details to establish Schmitt’s Pittsburgh bona fides, because unlike, say, August Wilson or John Edgar Wideman, her native land is barely present in the work. A Schmitt character might go on a school trip to the Carnegie Museum, or a soon-to-be-married couple will refer to their planned journey to Ligonier, but these are not tales about the soul of our city. They are universal stories about the souls of people on the edge and how, most of the time, they find a path to salvation.

What strikes the reader in 2015, encountering her stories for the first time, is just how contemporary the writing feels. She began to write in the era of Hemingway, but it’s not just the unadorned prose that makes her style transcend the decades. The settings reflect the era—there’s cigarette smoking, formal romantic courtships, train travel and a man putting aside the afternoon newspaper because “there was nothing in it that he had not already read in the morning paper.” Yet Schmitt’s characters are vexed by ills that ring familiar today.

“It never once occurred to him that there was nothing extraordinary about his case, that he was like other husbands,” begins “The Day Before the Wedding.” “He would not have believed that, out of twenty husbands chosen at random, as many as twelve might be urged into confessing that they had wakened on the day before the wedding totally devoid of the traditional bliss.” The story—first published in 1953 in Good Housekeeping magazine—is a tour de force of elegant invective. The husband-to-be, sullen because he expects that the paint job in their new apartment will be too dark after it dries, barks at his too-cheerful mother, and then rains contempt on his future wife as they bicker over a gift from “her silly family”—a reproduction of a Renoir painting, but “an atrocious” one, he says. “Of all the awful bathers, this is the worst.” Their exchange builds to pure rage—and a sharp, swift resolution.

Schmitt earns a reader’s laughter both from spikes of nervous tension and genuine delight. “The Matchmaker” contains my favorite of the latter variety: “He walked to the sinkboard and ate a radish and considered the depths of his own Machiavellian perfidy.” The radisheater is a husband, a symphony violinist, who returns home after Saturday rehearsal to find an extra guest for dinner—a piano student of his wife’s, invited to meet the gentleman bohemian painter who mooches dinner from them every Saturday.

The husband had arrived home with two crates of strawberries, ready to be made into jam, “chiefly because he had seen in them a means of ridding himself of the company of the young painter who sat mournfully around the house every Saturday night. He had hoped that his wife and the artist would spend a good half of the evening in the kitchen making the jam,” so he could take a bath and lounge around in his pajamas. The presence of the female student has thwarted his scheme, so he consoles himself with a radish.

Like most of the stories here, “The Matchmaker” wraps up with a happy or at least hopeful end, which might annoy a reader today accustomed to ambiguity or more comfortable with bleakness. A suspicious mind will see a commercial goal: Did a cheerful conclusion help place a story in the mass-circulation magazines of the day? The book’s introduction by Peggy Knapp, a longtime CMU English professor who knew Schmitt, swats down such a crass thought. “A good many of the stories end in what James Joyce called epiphanies: they concern protagonists who awaken from misjudgments of the social meaning and emotional tone of the situations and events they experience,” she writes.

Knapp’s concise and insightful essay is all the reader needs to gain a foothold in understanding Schmitt’s work, so this unlicensed amateur will cease with the textual analysis by citing her summation: “The stories, like many of her novels, demonstrate Gladys’s trust in imagination to bridge what some hold an unbridgeable gap between former generations and our own interior lives.”

But I’d like to leave the last word to Mary O’Hara of The Pittsburgh Press, who wrote the 1961 profile (and who had a distinguished career herself as society editor and political columnist). After ticking off the personal details that a personality profile for the women’s page had to address (dress size, favorite color, hair stylist), she sums up Gladys Schmitt thusly: “An extremely articulate woman, her conversation is nevertheless completely free of pedantry, affectation or artifice.”

Short Takes: New selections from Pittsburgh Authors

“Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature and American Cultural Diplomacy” by Greg Barnhisel

If the stories of gladys Schmitt make a reader pine for the days when popular magazines published ambitious literary fiction, “Cold War Modernists” stirs a parallel nostalgia: for when the most rigorous and challenging of American art and literature was held up as essential to the American way, not sequestered in academic or cultural cliques.

Sure, the threat of nuclear annihilation by the Soviets was one of the motivating forces of that golden era. But one must take the good with the bad, and Greg Barnhisel, an associate professor at Duquesne University and chair of its English Department, is an ideal tour guide. “Cold War Modernists” is a work of scholarship fully comprehensible to the general reader who is intrigued by the interplay of American culture and foreign policy and who is unflustered by the phrase “fundamentally antinomian” on the first page.

Barnhisel declares right off what he means by “Cold War modernism.” It’s not “new works in the modernist tradition produced in the Cold War years.” The term, which he has coined, “refers to the deployment of modernist art as a weapon of Cold War propaganda by both governmental and unofficial actors as well as to the implicit and explicit understanding of modernism underpinning that deployment.” In short: the freedom and individualism demonstrated by modernist art and literature was a finger in the eye of Soviet totalitarian control. American players in government, business and culture joined forces in this battle of ideas. His pithiest example: “Nelson Rockefeller memorably called abstract expressionism ‘free enterprise painting.’ ”

As with any important story about the United States of America, a Pittsburgher can be found at the red-hot center. James Laughlin, whose family put the “L” in J&L Steel, is best known for founding and funding New Directions Books, the influential publisher of modernist literature. News to me was his creation of Perspectives USA, which Barnhisel details with deep knowledge (he wrote a book about Laughlin in 2005). Published from 1952 to 1956 and funded by the Ford Foundation, Perspectives USA was designed to export the best of American culture to a mainly European audience. It would “bring together a panorama of what had been going on in American writing, philosophy, architecture, art, music, the whole cultural spectrum,” Laughlin wrote in his pitch. He lined up the most fertile minds of America to edit each issue on a rotating basis. The magazine was an initial hit, but like any committee with too many stakeholders, Perspectives USA could not sustain its mission; its contradictions “laid bare all of the problems inherent in using unruly modernism to champion Western culture.” Plus, the French edition was a flop: “They apparently just hate an American looking package,” Laughlin concluded.

Conspiracy theorists, who see the hand of the CIA behind every world event, will be disappointed that Barnhisel does not go for theories of government puppeteering. As he notes: “The State Department didn’t come up with the strategy to trumpet Western artistic freedom to counter Soviet accusations of American philistinery; rather, it (and, later, the United States Information Agency) adopted this argument from artists and cultural-freedom groups.”

“Cold War Modernists” provides enough anecdotal delights to enliven cocktail party conversation for months to come. My pick: When William Faulkner, fresh from his Nobel Prize, toured the world as an official U.S. cultural ambassador and authentically defended democracy and freedom of expression, the lover of bourbon was quite a handful for his embassy handlers. A wise diplomat stationed in Tokyo, Leon Picon, composed “‘Guidance Recommendations for Handling Mr. William Faulkner During Official Tours’ for all overseas posts that would host the writer. Those cultural affairs officers ignored Picon’s suggestions at their peril, and often ended up with an incapacitated Faulkner.”

But the real virtue of Barnhisel’s work is academic heft matched with accessible style, delivering a richer and more nuanced understanding of modern art and the forces driving it during a pivotal period in American history.