A century and a half ago, a desperate, down-on-his-luck former railroad man named Edwin Drake wandered into a remote hollow in northwestern Pennsylvania and stuck a drill a few dozen yards down into the rocky soil.

After a few false starts, Drake and his men struck a cache of crude oil that, while small by today’s standards, was big enough to set in motion a chain of events that would eclipse the nation’s young natural gas industry and would change the world, for good and for ill.

There’s talk these days in the drilling industry about whether something very similar could soon happen again.

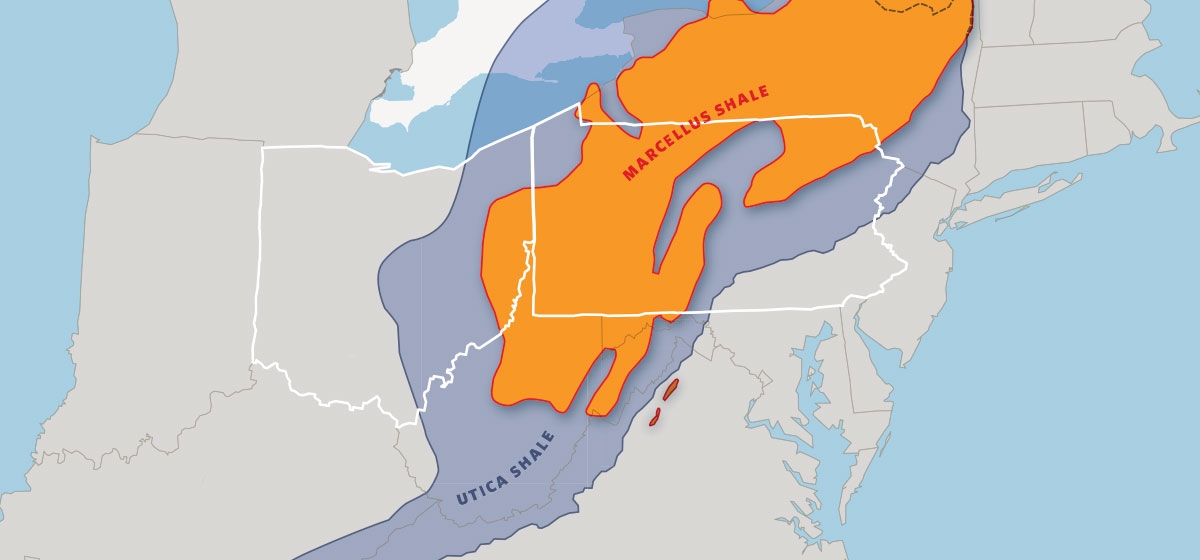

Right now, even as drilling in the vast, gas-rich Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania is expanding and is expected to expand further into neighboring states, drillers and energy analysts are casting covetous glances even deeper into the earth, at the Utica Shale, a layer of hydrocarbon-rich rock that runs beneath the Marcellus, stretching from Quebec to Tennessee. They’re also looking across our western border into Ohio, where the Utica is believed to keep its most tantalizing treasure. Oil. Lots of oil. Perhaps as much as 55 billion barrels of the stuff, enough to make the Utica Shale among the richest, if not the richest oil field in America.

“It’s big,” says Mike Arthur, a Penn State geosciences professor who, as co-director of the university’s Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research has been keeping a close eye on developments in the Utica as well. It’s not a new discovery, per se. The Utica Shale in Ohio in particular has long been a source stone for oil that pooled in easier-to-reach regions of the earth, and hundreds of wells have been drilled into and through it over the years. But the advent of horizontal drilling and slick water hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has made it possible to exploit the shale, releasing not only oil but the natural gas liquids it contains, such as ethylene, which can be extracted from the flow and sold.

There’s methane—natural gas—down there too. Ohio’s state geologist estimates that the Utica could contain about 16 trillion cubic feet of the stuff. That’s far less than the roughly 400 to 500 trillion cubic feet believed to be in the Marcellus, and much of it is thought to be of a lesser quality than the gas in the eastern parts of the Marcellus Shale. But that doesn’t matter. It isn’t the gas that’s drawing major corporations such as Chesapeake and Exxon to the Utica. “This is an oil play,” Arthur says, and that oil appears to be concentrated on the other side of the Pennsylvania state line, from eastern Ohio west to about the middle of the state.

Over the course of this year, several test wells drilled into the Utica in Ohio have turned up promising results, said Mac Swinford, Ohio’s assistant state geologist. Chesapeake, which drilled 12 wells into the formation this year, announced earlier this fall that all had produced significant amounts of oil, each producing about 1,000 barrels a day. And that has helped trigger a Marcellus-style land rush. In county courthouses from Portage to Franklin counties, land men are reported to be lining up at the deed books, trying to figure out who owns the rights to all that oil believed to be down there, and trying to sew up as many leases as they can.

For the moment, the rush is largely speculative. Though Arthur says there is little doubt that there is a substantial amount of oil in the Utica, there are a lot of questions about how efficiently—read that how cheaply—the oil can be extracted. Unlike much of Marcellus for example, the Utica is not believed to be uniform throughout, and geologists expect that drillers will run into dead zones, places where there is no oil. To compensate for that, they may find themselves drilling longer distances horizontally, and may have to frack the wells in multiple stages, more stages than are generally required to release gas from the Marcellus.

All of that adds to the drilling cost, a cost that could exceed $8 million a well. And it becomes an even more critical question if crude oil prices on the market remain sluggish; they hovered in the low $80 per barrel range early this fall, brought down by concerns over the stagnant economy. There’s also concern that news of this vast new oil supply waiting to be tapped might itself help depress oil prices, just as the unleashing of the Marcellus and other shales have helped keep natural gas prices in the under-$4-per-thousand-cubic-foot range.

So far, those concerns have done little to dampen the industry’s enthusiasm for what it seems to believe is the next big play. “This could be the biggest thing to hit Ohio economically since maybe the plow,” is how Chesapeake Energy’s CEO Aubrey McClendon put it.

Perhaps the more critical question for Pennsylvanians is what would the development of the Utica in Ohio mean for the Marcellus? That too remains an open question, experts say.

Some have expressed concern that expanded drilling and fracking in Ohio might place burdens on the industry here. Much of the wastewater generated by the fracking process here is trucked across the border to be injected into approved deep wells there, for example. And though officials in Ohio insist that with 175 such injection wells in that state, there’s plenty of capacity for now, it remains to be seen whether the widespread development of the Utica would alter the equation, either by shouldering Marcellus drills out, or by driving up the price to use those federally licensed injection wells, Arthur says.

For his part, Swinford contends that is unlikely to be a major problem in the near term. There are still plenty of deposits of porous rock across Ohio that could be drilled and accept wastewater from both the Marcellus and Utica. And the industry maintains that advancements in wastewater treatment and recycling have made the industry less dependent on deep well injection sites.

More to the point, the shale gas boom that began in Texas two decades ago and spread to Pennsylvania in the past several years has dramatically expanded the nation’s production of gas, but the markets for that product have not yet expanded with it. While natural gas has gained some ground, coal still remains a principal fuel for electric generation and natural gas has not made substantial inroads as a transportation fuel. That means that oil is still the coin of the realm. The question is, is that coin alluring enough to tempt the drillers in the Marcellus to alter their strategies and shift resources from parts of Pennsylvania to the oil-rich fields of Ohio?

It is far too early to tell whether the Utica’s oil shale will really turn out to be as prolific as the industry hopes and what that would mean to the industry here. One possibility, analysts say, is that drillers may move rigs from the southwestern parts of Pennsylvania, where the gas is loaded with liquids such as butane and ethane that can be stripped off and sold, into Ohio, where they can retrieve that as well as oil, while maintaining operations in the northeastern part of the state, where the gas comes out of the ground “dry” and almost market-ready.

Another possibility is that both plays will expand in tandem or that depressed prices will cripple them both.

But regardless of the outcome, the Utica is already a bargaining chip in Pennsylvania as the state gropes for more effective ways to regulate the gas industry, and for ways to share in the wealth it is expected to generate.

As Kathryn Klaber, president and executive director of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, put it, “resources don’t know political boundaries,” and drillers are more concerned with the bottom line than state lines. “What’s important to me every day getting up is the success of my member companies. Having them prosper is critical and they’re going to do what the market needs.”

Ohio is a state with a long history of accommodating the oil and gas industry and a current administration that has enthusiastically welcomed the attention the drillers have lavished on it. If Ohio offers the drillers an opportunity to make more money, that’s where they’ll go, she said.

“The importance of the policies of a state are magnified when you’ve got a dynamic as strong as commodity prices,” Klaber said.

Ultimately, however, few experts dispute that it will be the Utica itself and the price of a barrel of oil on the commodities exchanges, far more than comparative costs or regulations, that will determine the way forward. That’s what Edwin Drake discovered a century and a half ago in Titusville, and it is what drillers in Pennsylvania and Ohio are discovering as well.

As Klaber put it, “Commodity prices are going to rule the day, and if oil is fetching more than gas, we’re going to see more oil developed. That’s just the way the economics work in the energy field. It has everything to do with how much you can get for a barrel of oil versus 1,000 cubic feet of gas.”