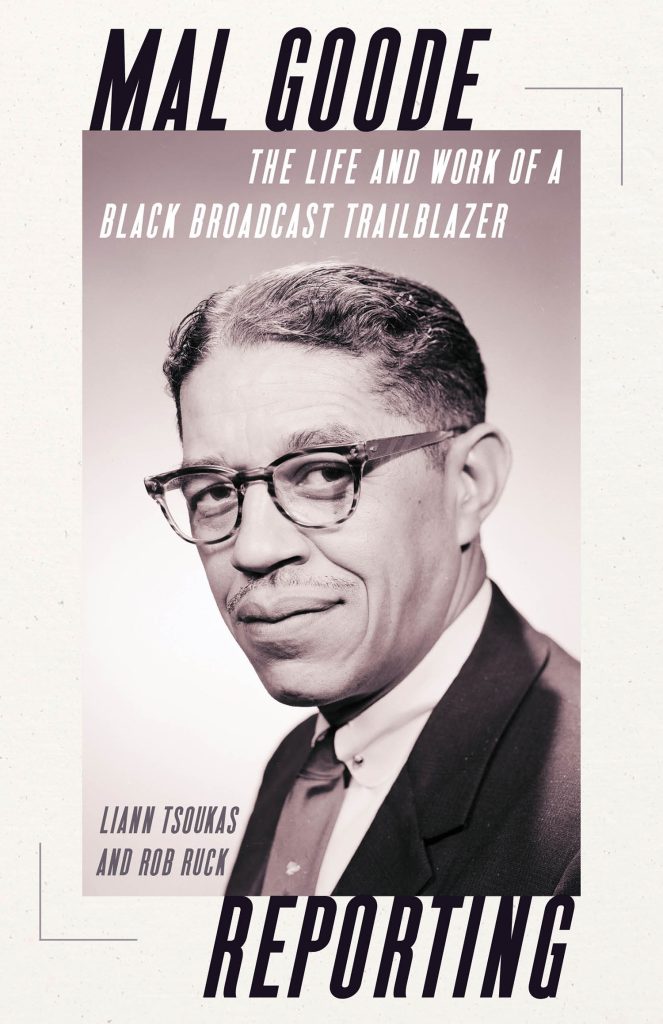

Pittsburgh’s Mal Goode: Television’s First Black Broadcaster

On Oct. 28, 1962, the three major television networks interrupted their scheduled programs to broadcast a special report on what would become known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. This was a critical moment not only in American history, but also in the integration of American broadcasting.

Just a few months earlier, ABC, at the urging of Jackie Robinson, had hired 54-year-old African American and Pittsburgh native Mal Goode, but, unsure of what to do with the first black broadcaster in television history, they assigned him to what was considered a minor beat at the United Nations. His reporting on the Cuban Missile Crisis changed all that, including the direction of Goode’s career.

Liann Tsoukas and Rob Ruck, distinguished colleagues in the History Department at the University of Pittsburgh, have written an outstanding biography of Mal Goode.

Well-written and thoroughly researched, Mal Goode Reporting: The Life and Work of a Black Broadcast Pioneer begins with Goode’s earliest days in Virginia, where he was born in 1908, and, at the age of 8, moved to Pittsburgh. It frames those early years within America’s history of slavery — Goode’s grandparents were slaves — and the Great Migration that included Goode’s father, who moved to Pittsburgh in 1890 at age 20 and worked in the Homestead Steel Works.

Raised by parents who insisted that he must better himself and go to college, Mal Goode worked in the Homestead steel mill cafeteria and on a sanitation crew while he was in high school. After graduating in 1927, he enrolled at Pitt, though he had to work his way through college to pay for his tuition.

Attending class at Pitt during the day and working a 10-hour shift at night with a sanitation crew, Goode experienced the best and worst of America’s racial divide, but even at Pitt, he encountered prejudice. After receiving a “C” in a course in which he made a “B” on all of his tests, he challenged the professor, who told him he shouldn’t expect the same grade as a white student.

Goode’s misfortune was graduating from Pitt in 1931 at the height of the Great Depression. While he wanted to go to law school, he kept his job as a janitor at the steel mill until he landed a job as a porter with Richman Brothers. Recently married, his life took a turn for the better when, after three years at Richman, he was offered a job as a probation officer and later as a supervisor at the Centre Avenue YMCA. The new positions and increased salaries gave Goode and his wife Mary a chance to move from Homestead to the Hill District, and it also gave Goode a chance to work with troubled black youths.

In a book that is well researched on so many levels of black history, Tsoukas and Ruck do their best work in placing the years Goode rose to local and national prominence within the social and cultural life of the Hill. Dismissed as a dangerous slum by white working-class families living just across the river on the South Side, the Hill, while so many of its residents were living in poverty, was also a vibrant social and cultural center. Great entertainers such as Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald often performed at the Crawford Grill, while some of baseball’s greatest ball players such as Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige played for the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords.

While Goode thrived in the cultural life of the Hill, he also grew more involved in the struggle against racial injustice. In 1942, he took over management of the Terrace Village and, shortly after, the Bedford Dwellings projects. He held those positions until 1948, when at the age of 40, he suffered a major heart attack that forced him to resign from his position at Bedford Dwellings. His family moved back to Homestead to live with his mother.

The heart attack had an immediate and devastating impact on his career and family, but it was the catalyst that would send him into broadcasting. Offered a position by a friend and editor at the Pittsburgh Courier of a less stressful job as the paper’s assistant circulation manager, he leaped at the “golden opportunity.” It was the beginning of his transformation from a community activist to a leading voice in the struggle for racial justice in Pittsburgh and eventually in America’s civil rights movement.

Goode became a broadcaster in 1949 when KQV, threatened by the popularity of television, offered two 15-minute spots to the Pittsburgh Courier with the hope of increasing its black audience. Jesse Vann, widow of Courier founder Robert Vann, impressed by Goode’s deep voice, precise way of speaking, and knowledge of the black community, offered him the broadcast. When Goode eagerly accepted the assignment, he started what would become an extraordinary career by broadcasting two 15-minute spots called “The Courier Speaks,” on Tuesdays and Wednesdays at 10 p.m.

When Goode’s broadcast became popular, KQV, after six months, decided to withdraw its offer to the Courier of free air time and wanted the paper to pay for ad time. Knowing Goode’s success and popularity, the Courier moved the broadcast to WHOD, a local radio station operating near the Homestead Steel Works.

When it first aired in 1948, WHOD catered to a blue-collar and immigrant audience, but when Goode joined the station, it had expanded its audience to African Americans, thanks to Goode’s sister Mary and her popular DJ show. By late 1951, Goode was WHOD’s news director and had daily news and sports broadcasts that continued until WHOD’s owners sold the station in 1956 to WAMO, which soon would become the major voice for Pittsburgh’s African Americans.

While Goode’s editorials at WHOD on racial injustice brought him his reputation in Pittsburgh as a champion of civil rights, his interest in sports as an opportunity for racial advancement became critical to his career. Not only did he interview visiting players such as Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, but he invited them to share a meal with his family. One of Goode’s fondest memories was watching Mays and Roberto Clemente dive into his wife Mary’s lima beans and cornbread.

When his tenure at WHOD ended in 1956, the same year that Jackie Robinson retired, he returned to the Pittsburgh Courier, but he continued to look for broadcasting opportunities. He had become good friends with Robinson, who knew of Goode’s frustration at failing to break through the “white wall” in local and national television. When Robinson heard that ABC’s new news director, Jim Hagerty, was interested in hiring an African American, he worked with Howard Cosell to arrange an interview for Goode. A few weeks after the interview, Goode received a phone call from Hagerty offering him the job. Goode told Hagerty, “I am the grandson of slaves. I never thought I’d see this day.”

In Goode’s 11 years at ABC, until his mandatory retirement in 1973, he became a major voice as a broadcaster and lecturer in the civil rights movement. He was an admirer of both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, though his beliefs brought him closer to King. He fought to improve ABC’s approach to black America and was furious when ABC did not assign him to cover King’s funeral, which he then decided to cover on his own. At his retirement banquet, Jim Hagerty called him the “Jackie Robinson” of broadcasters.

Mal and Mary Goode spent the next 20 years of their lives at their home in Teaneck, New Jersey, but, in 1993, at Mary’s urging, they returned to Pittsburgh. The move was important for Mary, but it also brought Goode back to his beginnings.

More than anything, his story is a Pittsburgh story. It was where he grew up under the shadow of a steel mill, where he first fought against racial injustice, and where his voice was first heard advocating for civil rights. And after his death in 1995 at the age of 87, it was in Pittsburgh, after so many struggles and challenges and so many triumphs and tragedies, where Mal Goode was laid to rest.