A Sailing Odyssey, The Conclusion

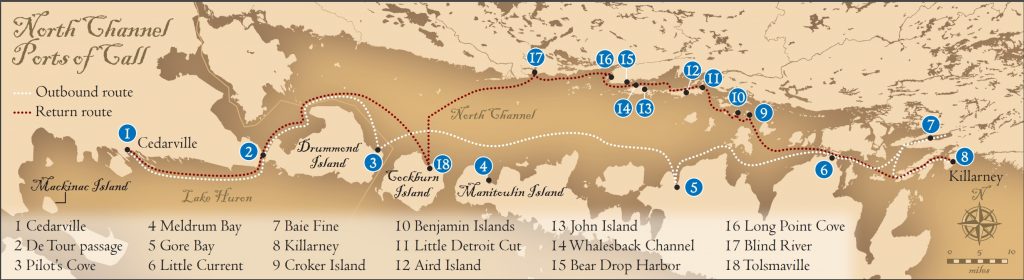

Killarney was our eastern apogee, where we spent the rainy day in the Killarney Mountain Lodge, had drinks by the fire and I taught the guys to play bridge. From there we started the long trek back, exploring the North Channel’s most beautiful places by day and playing bridge in the cozy cabin each night. On a boat, there are long stretches when nothing much happens. Hours pass, even days, just enjoying nature and appreciating being alive. Such tranquility, though, seems destined to become its opposite. And just as anxiety is an inevitable part of getting underway, so too does it seem that you can’t return home without a final test.

My sons and I had faced that. In a heavy wind just five miles from home, one of the genny lines somehow wrapped around the prop, leaving us drifting between two reefs without our best sail and our engine. Though the mainsail alone isn’t very effective, we made it back after a four-hour battle with the gusting wind.

I hoped to avoid any more drama on this trip. But ahead of me was the last challenge, crossing from the top of the North Channel to the bottom. During breakfast in Blind River, a small Canadian mainland port on the Channel’s northern rim, I was watching weather reports and considering our options. From Blind River due south, the crossing was 20 miles, but ideally we’d cross diagonally, which would get us closer to home but add another 15 miles to the trip. We had to cross at some point. The question was whether to do it that day when the wind was expected to blow 10-12 miles an hour or the next when there’d just be a slight breeze and virtually no waves.

I’d sailed in eight-foot waves with the boys three years ago, and it was intense. I never felt it was dangerous though, because we were always within half a mile of shore. If the waves had built to 10 feet or more, we could have ducked into the quieter waters in the lee of the land. I was determined to avoid anything like that on this trip, especially getting caught in heavy wind and waves far from shore.

The Blind River harbormaster suggested I cross that day. Winds at 10-12 wouldn’t be bad, he said. I’d get much closer to my destination to the southwest, and the waves were just one to two feet, currently. When two other boats came into port, I asked their skippers what conditions were like. One said it wasn’t bad at all. Another agreed but said he wasn’t going back out that day. “We’re in the lee here, and it’s misleading,” he said. “I think it’s going to build.”

I spoke with the harbormaster again, asking how often the forecast changed there. “It won’t change much, so you might as well just cross and get it over with.” I decided to take his advice, setting a west-southwest course for Drummond Island, 35 miles away. But I did so with an uneasy feeling.

It was a clear day as we left the harbor and two miles later, when we passed the shelter of the Canadian mainland, we felt the full northwest wind. It was still early, about 11 a.m., and the wind was blowing about 10 miles an hour, with two- to three-foot waves. Nothing remarkable, and we sailed on. By noon, the Canadian mainland was four miles behind us, and the cliffs of Manitoulin Island to the south were just faintly visible some 18 miles away. By 1 p.m., I estimated the winds at 15 — above the day’s top forecast — and three-foot waves, maybe four. If it stayed there, no problem. The guys were having a good time. Good for them. Another 25 miles to go.

By 1:30, we were in four footers with winds at maybe 18. No need to estimate how far we were from land either to the north or south. We had committed to the crossing, and I just sailed the boat. We didn’t have the mainsail up. We didn’t need it in that heavy wind. The power of the bigger genny was all we needed, maybe more than we needed. And at 1:45, I asked the guys to reef the genny. By partially furling the big sail, we’d have less sail area out, essentially depowering the boat in this strengthening breeze. In other words, there was more wind than we wanted.

By 2 p.m., I was in my own world, concentrating intensely on sailing as the others chatted. The boat was doing fine. The trouble was not conditions as they were; it was what they might become. We were well into the middle of that big body of water, a good 10 miles from land on either side. We were sailing in five footers, plunging down and rising up as we sliced into them on an angle. I analyzed the situation constantly, and the more I did, I started getting a queasy feeling. It wasn’t seasickness. I’m prone to that but only when I go into the cabin while we’re moving. This was different. This was the realization that I was responsible for my friends, and that if the waves built from their current five feet to eight or 10 or more, there wasn’t a thing I could do about it. It was exactly what I’d wanted to avoid, and here I was with no option but to sail through it for the next four hours and hope.

It was a change from Baie Fine when the guys were worried about sinking and I wasn’t. Now, they were having fun and I was filled with dread.

This would be my private ordeal — a North Channel challenge special-ordered just for me. Time slowed to a crawl, measured wave by wave. And Gordon Lightfoot’s great song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” came to mind. “Does anyone know where the love of God goes, when the waves turn the minutes to hours?” As much as I’ve liked that song for 45 years, I never truly appreciated the searing truth of that line until that moment. The awareness, however, gave no solace.

Moments later, I interrupted the guys and told them we had to put on life jackets. Their faces registered sudden recognition of possible danger, and from then on, they kept a weather eye on the western horizon to gauge what was coming. For me, though, once we all wore life jackets, the queasiness subsided. I didn’t expect a disaster, but if it came, at least we’d all survive.

The writer’s friends, (from left): Jeff Bell, David Guenther, and Colonel Geoff Catlett

In this weather, there’d be no one to relieve me on the helm, and the best thing was to occupy at least part of my mind with chatter. I quickly asked a couple of forced questions, including a staccato “What are your top 10 movies?” realizing instantly we’d discussed that days earlier and that my repetition had betrayed my state of mind. Up and down we went, and some time later — who could say how long? — I asked them to reef the genny again, further reducing our sail and speed. By then, I guessed it was blowing over 20, and occasionally we plunged through a six-foot wave.

When they finished reefing, I announced we were altering course — forgetting about making Drummond and instead heading due south to the nearest land — which I figured was Cockburn Island. It would cut two hours off the trip, and I guessed it was eight miles, or two hours away. It was a no-brainer, and we sailed on, with the outline of Cockburn slowly turning from indistinct gray to darker green the nearer we got. To change their mood and mine, I yelled in a pirate voice, “And an extra measure of grog to the first man who can make out an individual tree on Cockburn!”

We consulted the GPS to make sure it was Cockburn we were heading for and to find out exactly where the tiny port of Tolsmaville was on the land mass ahead. The wind was literally howling in the shrouds as we made our way. We’d later learn it was blowing 25 with gusts up to 30. The white caps rolled from right to left as we cut across them.

With our destination coming more clearly into sight about an hour away, our spirits lifted as the Colonel and Bell traded turns on the binoculars, scouring the shoreline ahead for the harbor. I headed for where I thought I remembered the marina to be. And the Colonel finally called out, “I see it! I see the breakwater! The surf is smashing against it!”

We were on target and as we got within a mile, the only thing that remained was furling the genny completely, so we’d be in a controlled approach, under engine power only. The trouble was, the furling mechanism sometimes stuck, which it did presently. That required someone to get on the bow and turn it manually as someone else pulled the rope from the cockpit. In these plunging five- to six-footers, I didn’t relish asking anyone to crawl up there. I’d feel better doing it myself, but I couldn’t leave the helm. Bell was the only one I felt comfortable asking, the one I thought had the best chance of battling those elements without mishap or injury — but there was no guarantee.

And so it was that he crawled up along the high side, holding the guidewire with his right hand and grabbing the contours of the deck with his knees as he made his way to the prow where the sprocket awaited. Back in the cockpit, Guenther was poised to pull the line, furling the rest of the genny as soon as Bell signaled. The gusting wind and plunging spray made communication nearly impossible, but we heard Bell yell “Okay! Do it!” Guenther heaved the line in, cleated it, and the genny was furled. Bell made his way like a cat back to the cockpit to a hero’s welcome with whoops, handshakes and claps on the back.

Finally, we made the right turn into port, exiting the roiling bay and reaching the incongruously calm waters behind the buffeted concrete breakwater. After nearly six hours of intense sailing, I heaved as big a sigh of relief as I can remember. We tied up at one of the many empty slips, as the waves thundered against the cracked, old breakwater, the spray shot up, and the wind howled. Moments later, Guenther handed me a glass of straight Scotch and, with a knowing look and a smile, we shook hands.

***

When at last we sailed into our home port, we all felt triumphant and relieved to be on terra firma. At the local fish restaurant, we toasted each other and the voyage. For the guys, it was an epic adventure, and they compared it, in turns, with the Odyssey and Jason and the Argonauts. If we did it again, someone said, we could charter a bigger boat. I nodded and laughed, even though I now loved that old boat that had delivered us safe and sound.

I was mainly relieved my responsibilities were finished. In some ways, it was more than I’d bargained for. And that night, I thought I’d probably never do it again. I recalled an old Pittsburgh friend who sailed the North Channel solo every summer, ultimately dying on his boat there at the age of 78. I was 60 now. I didn’t need the danger. Didn’t need the anxiety.

And yet, in the months since then, the travails have faded and the highlights remained. It was an epic challenge for me too. I’d gotten better as a skipper, better at knowing what to do and what not to do. I made the 325-mile voyage with a green crew, navigating the waters, the winds and the human complexities. I’d exercised the necessary authority with some nuance, apologized when appropriate and, through everything, had kept the four of us on good terms despite close quarters.

We’d battled the elements together. And we’d been tested, each in his own way. And now, as the winter sets in followed by our remaining years ahead, we’ll tell our own tales around the fire: a story about four old friends, graybeards all, who sailed to the far side of their world, heard the siren song of the north and returned safely home again.