Who is That Guy, Anyway?

Collecting is an addictive passion. My wife and I collect architect-designed chairs, carved and inlaid wood items, textiles, bakelite dress clips, pre-Revolutionary maps of New England, miniature hats and, perhaps the strangest, glass swizzle sticks with a Pittsburgh provenance.

My main collecting interest over the past 25 years has been fine art prints and watercolors of Pittsburgh scenes from the early 20th century. The result is a thoroughly congested den and a total absence of empty wall space in our home.

The true, passionate collector is not interested in the mere accumulation of objects, though having “too much stuff” is often the result. What’s interesting is the story behind the object: where it came from, who once possessed it, the creative process behind the item, its value, and, of course, whether one got a “deal.” For many collectors, the “quest” may be the most important aspect. It’s not just the physical search for the item; the quest is a thorough exploration of and relentless probing for all information about the object.

This quest began with an inquiry from Graham Shearing who was writing a Pittsburgh Quarterly article on visiting artists who were captivated by Pittsburgh. I showed Graham an etching of a baseball player done in 1904 by French artist Jean-Emile Laboureur (1877-1943). He was intrigued. Laboureur was certainly an outsider, but Graham felt the print was so rare that it demanded an article of its own.

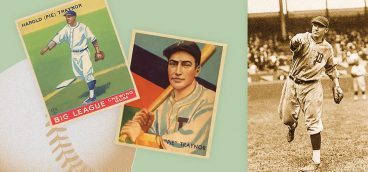

The print is rare. Laboureur wrote on the reverse “2 ou 3 epreuves-pl. rayeé” (2 or 3 proofs — plate cancelled). Besides my print, the only other known copy of the image is in a private collection in France. Graham asked the identity of the player depicted. I suspected it might be Honus Wagner but had never tried to confirm it. Graham mentioned that the most valuable baseball card in the world, the Piedmont T206 Honus Wagner, sold in 2000 on eBay for $1.265 million. There are approximately six of them, in various conditions. A comparison of rarities indeed, although I would gladly trade my print for the Holy Grail of American baseball memorabilia, a T206 Wagner. But I was hooked, and the quest was on.

When I acquired the Laboureur etching from a print collector-dealer in the Midwest, I knew of its rarity, owning several of his Pittsburgh images, but I was much more interested in the etching’s connection to Pittsburgh. Laboureur arrived in Pittsburgh on Jan. 13, 1904, intrigued by the wonder of work and the industrial capitals of the United States. He was also amazed at the conspicuous consumption of the social elite. Laboureur had an education in art history and a style influenced in part by Toulouse-Lautrec, whom he had met in 1896. Laboureur’s style is similar to the decorative work of the French graphic avant-garde.

Connection no. 2

Rina Youngner is the author of “Industry in Art—Pittsburgh 1812-1920” and my second connection in the quest. As part of her doctoral thesis, Rina acquired copies of many of Laboureur’s letters home during his 1904-1906 stay in Pittsburgh. She got the letters from the artist’s son, Sylvain, who lived near Paris. They tell of the young artist’s first visit to the U.S. and his attempts to find patrons in Pittsburgh, while absorbing the nation’s industrial might.

Laboureur was entertained at the Duquesne Club and at parties in Sewickley; he was introduced to the social and business elite of Pittsburgh’s gilded age. He produced two successful series of etchings (10 prints each) while in Pittsburgh: “Ten Etchings from Pittsburgh, 1905” and “In the Pittsburgh Mills, 1906.” The subjects ranged from mill workers’ tenement houses to the view from the 16th floor of the Frick Building.

One exceptional print I located in Paris, “La Blanchisseuse Negre” (The Black Laundress), which was done separately from the two series of etchings, depicts a woman hanging laundry in the back yard of a home in Shadyside, close to where Laboureur rented his Pittsburgh apartment. The second set of etchings depicts steelmaking from his visits to the Edgar Thomson Works. According to Rina, this is the first representation of steelmaking inside a steel plant presented as high art. These Laboureur images of Pittsburgh are exceptionally rare, but the Carnegie Museum of Art collection has examples of both sets.

Among the purchasers of his work were the most important patrons in the city: Henry Clay Frick; Dr. William Holland, the first director of the Carnegie Institute’s Museum of Natural History; Edgar Kaufmann; Rabbi Leonard Levy of Rodef Shalom; and John Beatty, director of the Carnegie Institute’s Department of Fine Arts and prime developer of the Carnegie International. Others included the Carnegies, Childses, Woodwells, Thaws, Chalfants and Negleys.

Could Laboureur’s letters to his parents provide clues as to the identity of the baseball player in the etching? I asked Rina to check. She uncovered nothing new, however, except a mention in a July 12, 1904,

letter that Laboureur was finishing a sport picture of the “National Game.”

The greatest ball player

John Peter (“Honus”) Wagner, “the Flying Dutchman,” was as important in the 1904 sports community as Clemente, Bradshaw and Lemieux are to my generation. As quintessentially Pittsburgh as a Tessaro’s Pittsburgh rare burger or a Primanti sandwich, Wagner was a monumental figure in his time. Born in 1874 in Mansfield, Pa. (now Carnegie), he was the son of a coal miner, and his first job at 12 was in the mines and manufacturing hearths. He was one of five brothers who all played baseball; they were known as the Wagner Brothers ball club. “That’s how I could play all positions. On our family

team you had to know how to play everywhere, as we were always shifting,” Wagner said.

When Wagner retired in 1917, at the age of 43, he held more major league records than any player in history, including eight batting championships. He led the Pirates to pennants in four years and played in two World Series. In 1905 he became the first player to have his name branded on a Louisville Slugger. In 1936, Wagner, along with Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, was among the first five inductees to Baseball’s Hall of Fame. Cobb, not one to easily praise a competitor, said, “Wagner is the greatest ball player that ever lived.”

Even though he became acquainted with the likes of William Howard Taft and Henry Ford, Wagner was a regular guy. During the baseball season, he often rode the 10-cent streetcar from Carnegie to Pittsburgh and then changed cars to get to Exposition Park on the North Side, where the Pirates played until Forbes Field opened in 1909. It was said that Wagner attracted fans along the entire route who asked for stories about the game or the Pirates’ chances. He was shy and unpretentious, and he loved to fish and hunt. Although other teams offered more money, Wagner never left Pittsburgh and lived in Carnegie his entire life. He married Bessie Smith of Crafton, built a home in 1917 on Carnegie’s Beechwood Avenue and lived there until his death in 1955.

The artist’s son

A catalogue raisonne of an artist’s work attempts to document all images produced by the artist. In Laboureur’s case, there are three published catalogs. The most definitive was produced by his son, Sylvain, in 1989. The Sylvain Laboureur catalog provides a list from his father’s August 1904 sketchbook, an “American Notebook,” of a series of five etchings dedicated to baseball for which “there are no proofs.” The list from the American Notebook lists five images: baseball player (batter), the catcher, the umpire, the infielder and the pitcher. According to the catalog our “joeur de base-ball” (baseball player) is the “only survivor from a series that was probably finalized to the point of becoming a print and for which we have some other traces; other sketches in some notebooks and a list where the plates are presented as having been completed. Having returned to Europe, the artist judged that these subjects could not have interested the clientele of the Old Continent.”

So Sylvain Laboureur might be another source for the quest, connection No. 3. Was he still alive? Would he still have access to this “American Notebook” and perhaps forward copies to me? Are there other letters from the spring and summer of 1904 which might nail down the identity of the baseball player etching?

Enter connection No. 4. Madame X is my esteemed print dealer in Paris, a source, for entirely selfish, personal collecting reasons, I am reluctant to reveal. Madame X was extremely generous, but was she willing to join the quest? I told her of the project. She wasn’t aware that I owned the rare Laboureur image of the baseball player. Yes, Sylvain was alive and she would contact him on my behalf. So began a series of e-mails and letters to France. I wrote in English, and X translated into French for Sylvain. Sylvain wrote back in French. X translated into English. In forwarding me copies of the sketches from the “Notebook,” he said that the notebook from that time frame also contained other projects, such as the one on the “Negresse etendant son linge” (Black woman waiting for her laundry) and the aforementioned “La Blanchisseuse Negre.” Sylvain wrote, “Please excuse this racist-seeming expression with no link to my father’s ideas of the time.”

He forwarded copies from pages of his father’s sketchbook depicting drawings of baseball subjects during his 1904 visits to Exposition Park and copies of his father’s notes from the “American Notebook.” He hadn’t located any more proofs or engravings corresponding to the baseball series, other than the one reproduced in the catalogue from the private collection in France. As for letters, those that exist are in the hands of a woman in France who is completing her doctoral thesis on Laboureur’s time in the U.S.

Sylvain didn’t want to disturb the researcher’s work, so I’d have to wait on that front.

The fifth connection

I turned to the next source, David Conrad, who is not only a Pittsburgher and accomplished actor, but also a baseball savant. I gave him a copy of the Laboureur print and copies of the sketchbook images. If I could give him the date Laboureur actually visited Exposition Park, he could get me the box score of the game, the opponent and perhaps determine some of the names of the players in the drawings. One of the drawings appears to depict a left-handed catcher — very rare. The Pirates had one in 1903 but not 1904. When I realized I wasn’t going to find a specific date, it was clear that an analysis of the etching image would have to become the crucial means of identifying the player.

Conrad’s believed the print looked like Wagner. Wagner was bigger than most ballplayers of that era, not in height but in girth. He wore his cap very low, like the player in the print.

He had the jutting jaw you see in the print and that broad, German nose. Wagner wore his socks high; they looked as if they were tucked up under the knees, just as in the print. He was noted for his bowlegged stance, and the player in the etching is bowlegged. But according to Conrad, the biggest proof is the lack of the knob at the bottom of the bat. Wagner often hit with a bat that didn’t have that bottom knob. Power hitters then didn’t require it. Today, they do, so they can hold onto the bat as they torque it. Conrad also noted the close comparison between the etching and the series of three drawings on one page of the sketchbook. The squatting player resembles how Wagner set up as an infielder, straight back, hands out and open, making him almost completely symmetrical. There are many photos of Wagner in this posture. The third drawing is a right-handed batter. His pants and hat seem similar to the player in the print. His feet are turned inward, bowlegged like Wagner’s.

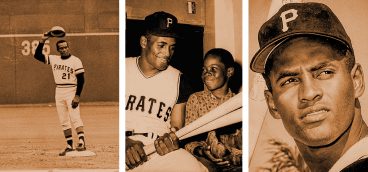

Conrad showed the print to another baseball cultist in Los Angeles, whose first response was, “Oh, it’s Wagner.” I mentioned I was going to visit with Duane Rieder, who had previously seen the print. Conrad felt Rieder’s opinion would be conclusive. Rieder probably knows more about Roberto Clemente than anyone alive and is preoccupied with Pittsburgh’s baseball history and the preservation of important archives and memorabilia.

I asked Rieder, my sixth and final connection, whether he’d ever seen a photo of Wagner batting with his hands apart as is depicted in the etching. He said such a photo exists, and he had a book with that iconic image of Wagner’s hands apart holding a bat. This photo was uncovered in the Ken Burns’ special on baseball. It was taken in 1912 by Charles Conlon, who said Wagner was the only player who would permit him to photograph the distinctive grip. Before I could get over to Rieder’s studio, my oldest son, Kendal, located the photo, the original of which is in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

To Wagner, a batter’s grip was critical. He usually choked up a little, but often he would split his hands a few inches. This split-hand style, not uncommon in 1904, is exaggerated by Laboureur in the print. This style was often referred to as the Wagner-Cobb grip, since Cobb also used it. Sometimes Wagner would keep his hands together and then split his grip to make better contact, often when he had two strikes. The split-grip is also used to make it easier to direct the ball into right or left field, depending on the situation.

Rieder also said Wagner liked a 35-inch bat, longer than most players of the era, and often used a heavy bat, sometimes 38 ounces or more. He called it a tree trunk, and the bat in the etching looks like a monster club. In those vintage photos of Wagner kneeling before a parade of bats, the one in his hand is the largest of the group. Laboureur exaggerated this in his image.

Wagner normally batted right-handed, but sometimes he stepped to the left side of the plate. The image in the Laboureur print appears to depict a left-hander. However, when one recognizes that the printed image is a reverse of the etched plate, it is clear that a right-handed batter is the subject of the print.

When Laboureur went to Exposition Park to see our national game for the first time, Wagner was the sport’s greatest personage, and he played with abandon. The Pirates had won the National League pennant in 1902 and 1903 and were in the first World Series against Boston in 1903. In 1904, Wagner was the star of the team. If Laboureur were going to draw a baseball player, he would have selected the most important player, not some rube. Wagner also clearly represented the blue-collar type of personality Laboureur would later depict in his industrial views of the city.

Finally, when depicting a scene or object, an artist tries to reflect the essence of the subject. Laboureur’s etching is not meant to represent an exact reproduction of Honus Wagner. In depicting the large, bowlegged player, his hands apart, jutting jaw, broad nose, low cap and big bat, Laboureur has captured the essence of the Flying Dutchman. So in this case, my quest ends with a bottom of the ninth grand slam. There’s nooooooo doubt about it! Anyone want to trade for a T206 Wagner?