A Great Mind Ponders Grim Alternatives

For readers who missed part 1 of this series of posts, I am summarizing a fictional novel written almost forty years ago.

When George suggested that Grace Atkinson be summoned to the deliberations on the Eastern Shore, not everyone was enthusiastic. For one thing, Grace was recovering from a stroke.

Moreover, as one Panel member put it, what difference would Grace’s presence make?

“I think about it like this,” said George, who had voted for Plan A—i.e., that he beard President Johnson and threaten to convene a press conference if Johnson didn’t cancel Black Hole. “If Grace votes with me, that will give us six votes. We’ll only have to convince one of you annoying holdouts and we’ll have seven.”

“On the other hand,” replied the Panel member, “if Grace votes for Plan B [sending the Black Hole file to the newspapers] the vote will be tied, 5-5. We’ll only have to convince two of you recalcitrant bastards and we’ll win.”

Everyone had a good laugh, but, as usual, George got his way. He suggested that Jenny fly to Chicago and try to convince Grace to come to Maryland.

Jenny was, for sure, the right choice to go. Although she and Grace had never met before the Georgetown Convention was organized, the two women had become close over the months. They tended to see eye-to-eye on the issues and even when they didn’t, their disagreements were respectful.

But what Jenny didn’t know was that Grace had lied about her medical condition. Grace hadn’t suffered a stroke and was recovering—she had cancer and was dying.

Grace had been invited to join the Georgetown Convention, and then to serve on the Approvals Panel, because she was probably America’s leading Constitutional scholar. At the age of 76, Grace was now emeritus at the University of Chicago Law School, but she was still a formidable intellect and a force to be reckoned with in the hothouse world American Constitutional scholarship.

The culture wars of the 1960s and hostility to the War in Vietnam had profoundly changed American universities and that included law schools and Constitutional scholars. The term “politically correct” wouldn’t acquire a pejorative connotation until 1987, with the publication of Allan Bloom’s “Closing of the American Mind,” but even by 1971 the trend was powerful.

The received wisdom about the American Constitution already went something like this: It was a document created by an elite group of educated and affluent males, designed to serve the purposes of people like themselves, and had done so for nearly 200 years.

Interestingly, Grace Atkinson agreed with this description of the Constitution. Where she differed from the PC crowd was this: she thought that that was exactly how it should be. Yes, the framers were an elite group of people who happened to be all male for purely historical reasons.

And, yes, they had created a document that worked for them and people like them. But—and it was huge “but”—it had also worked for virtually everyone else. People living under the U.S. Constitution, or similar documents modeled on it, lived freer and better lives whether they were elites or non-elites, rich or poor, black or white, male or female.

The Constitution wasn’t perfect—hell, nothing is perfect—but it was, in Grace’s words, “the most perfect governing document ever drafted.”

Before Grace was invited to join the Georgetown Convention, she had already begun work on a book that would be her “magnum opus.” The book would make the arguments summarized above in great detail and with many historical references.

But after working with the Convention for seven months (of its, so far, nine-month life) Grace had been diagnosed with a rare,fast-growing and inevitably fatal form of brain cancer. Her doctors gave her no more than six months to live.

Since self-pity was an emotion unknown to Grace, she promptly reassessed what was left of her life. She needed to stop spending so much time on the Georgetown Convention and a lot more time on her book.

But as Grace turned to the book with renewed determination, she recognized, reluctantly, that she wouldn’t have time to finish it. Instead, she arranged to publish a shortened version of the book in three consecutive issues of the University of Chicago Law Review.

That is how the situation stood when Jenny Leader innocently rang the bell at Grace’s Hyde Park apartment on the south side of Chicago. When Grace opened the door, Jenny at first thought she was being greeted by an elderly cleaning lady. Grace had failed so much in two months that Jenny simply didn’t recognize her.

The two women sat down to tea and Jenny did her best to convince Grace to come to Maryland—without, of course, spilling the beans about Project Black Hole. But she soon saw that it was hopeless. Grace was determined to finish her law review article and she wasn’t going to let the Georgetown Convention interfere.

“You have nine good people on the Approvals Panel,” Grace said. “Pick someone from the working groups or the task force to replace me. I’ll send you some names if you would like.”

Jenny stood up and paced around Grace’s small living room for several minutes. Then she turned to Grace and said, “If you tell me the truth about your illness, I’ll tell you why it’s so important for you to come to Maryland.”

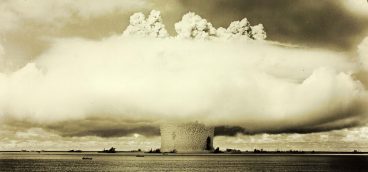

Less than an hour later Jenny knew that Grace was dying and Grace knew that the President of the United States was about to unleash nuclear weapons on the world with no public or Congressional oversight.

Grace pondered the matter for a very long time, then said, “If you can find an ambulance that will take me that far, I’ll come to Maryland.”