The City of Pittsburgh Faces Crisis but Its ‘Rainy-Day Fund’ Leaves It Better Prepared Than Most

In a letter to the White House Monday seeking federal support, Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto projected a 21 percent loss in revenues this year. The expected $127 million loss will plunge the city into a financial crisis, but that blow may be softened by a little known rainy-day fund.

“Over a five-year period from 2020–2024 the City expects to lose a total of $239 million, which amounts to a 7.5% cut,” the Mayor wrote. “These estimates are extremely fluid and will likely change depending on the length of business closures in the City. The tax revenues that are most in peril are payroll, parking, earned income and property taxes: these four taxes alone could see $97 million in losses just this year.”

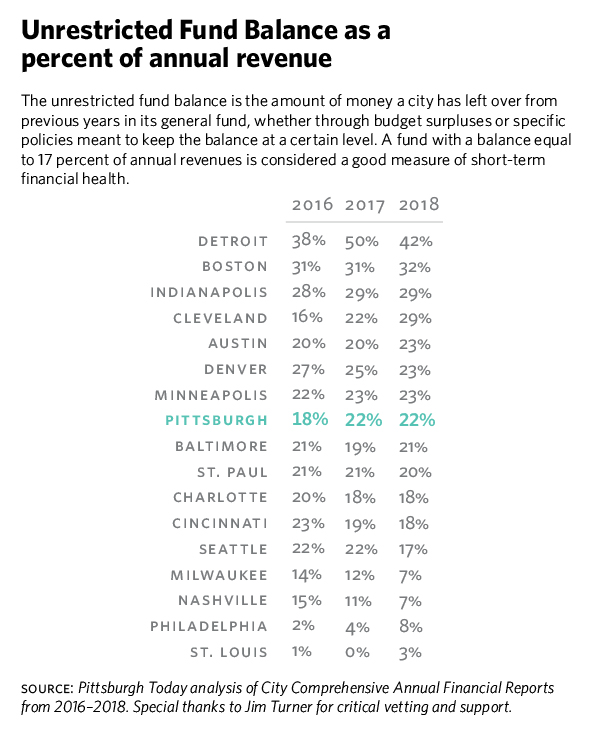

Pittsburgh, however, may be better prepared for the revenue crunch than many cities because of what is known as its unrestricted fund balance—the amount of money a city has left over from previous years in its general fund, whether through budget surpluses or specific policies meant to keep the balance at a certain level.

The City of Pittsburgh’s unrestricted fund balance is higher than what experts recommend and on the higher side compared with Pittsburgh Today’s 15 Benchmark cities.

“The unrestricted fund balance is basically your rainy-day fund, it’s your savings account,” said Michael Lamb, Pittsburgh City Controller. “When that number is up, it’s a very good indication of short-term health.”

While no part of the nation will be spared severe economic trauma from the pandemic, experts say cities with consistently healthy unrestricted fund balances are better positioned to weather the looming fiscal crisis.

“It’s a big deal,” said George Dougherty, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public and International Affairs. “It will be highly significant depending on the types of services they provide.”

A penny saved

Having an unrestricted fund balance of no less that 17 percent of revenues for the year is a practice that the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) recommends cities adopt. A balance that size translates into about two months revenue for the year.

As of the end of 2018, Pittsburgh’s unrestricted fund balance stood at $124 million, about 22 percent of its revenues.

Michael Mucha, the Chicago-based director of the GFOA’s Research and Consulting Center, said that larger cities with more diverse revenue streams could responsibly keep their balance below 17 percent. But smaller cities and communities with more unstable revenues would be smart to aim for a balance significantly above the threshold. “What’s important is that cities consider their specific risk factors,” he said.

For the past three years, Pittsburgh’s unrestricted fund balance has steadily hovered slightly above the GFOA’s recommended 17 percent threshold. Among Pittsburgh Today benchmark regions, Austin, Denver, Minneapolis and Baltimore have balances similar to Pittsburgh’s. Detroit has a whopping 42 percent unrestricted fund balance, the highest among benchmark cities. St. Louis has the least cushion against the financial hardships to come with a balance of only 3 percent. Philadelphia doubled its unrestricted fund balance from 2016–2018. Still, it represents only 8 percent of its budget.

Uncertain months ahead

The severity of the economic pain inflicted by the pandemic remains unknown. So, too, is how unrestricted funds will be used. It’s likely, however, that a portion of them will be used to shore up essentials, such as emergency medical services.

But even dipping into a healthy unrestricted fund balance won’t prevent the city from running a deficit, Lamb said.

On a national level, Dougherty said the pandemic underscores the importance of a healthy rainy-day fund. “Running surpluses and planned unrestricted fund balances are just good practice for the things that we can’t predict.”