Was Herbert Simon the 20th Century’s Galileo?

In the mid-1980s a journalist visiting Carnegie Mellon from France suggested that a statue of Herbert Simon should join those of Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Galileo and Bach in front of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute. At the time, I considered this a bit of Gallic hyperbole, but now I don’t.

Simon came to Carnegie Tech in 1949 along with some other future Nobel Prize winners to start a business school, GSIA. They pioneered the scientific approach to business. When other universities got wind of this new approach, they raided the GSIA’s faculty. Most left for the coasts, but Simon stayed until he died in 2001, remaking the university in his quest to understand intelligence.

He made many scientific contributions, but two of them have deep implications for humanity. The first was his claim that humans were not completely rational. No one doubts this today, but he fought a long battle with economists who preferred to assume humans were completely rational because it allowed them to create mathematical theories. His followers have vanquished such thoughts. Daniel Kahnenman received a Nobel Prize by illustrating exactly how humans err in decision-making and many have followed into the new field of behavioral economics.

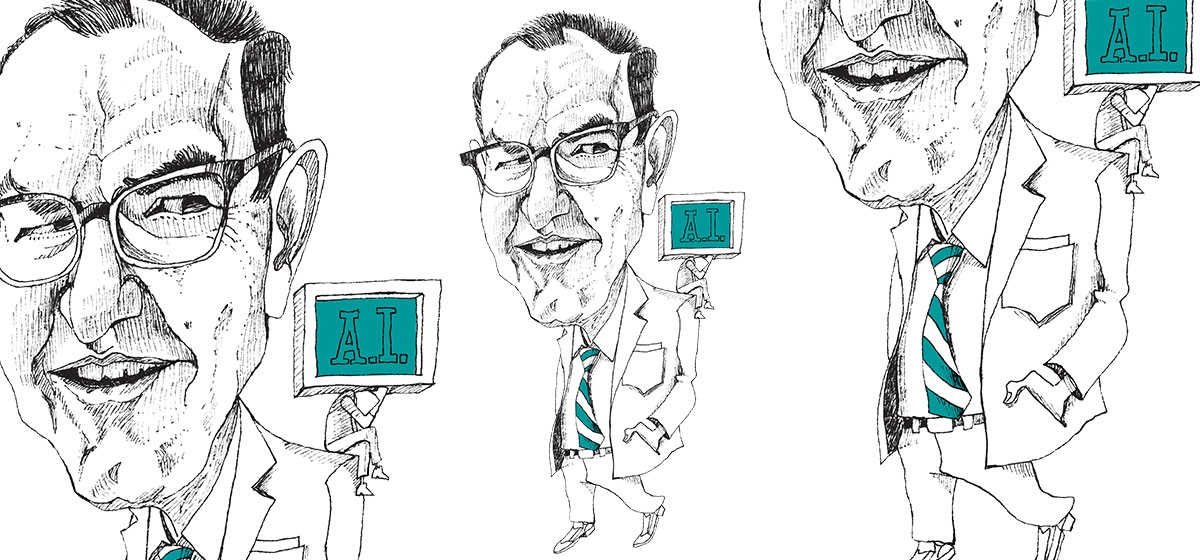

His second major claim was that a computer could, in principle, do anything a human could. This also seems obvious to any materialist, someone who doesn’t believe in any divine human attributes. He and his colleagues created the field of artificial intelligence in the 1950s and set about demonstrating computer simulations of every conceivable human talent. Public opinion about AI, as it is called, has had many ups and downs. It is currently sky high with computers running factories and investment funds, beating world champion board-game players and scaring the bejesus out of famous geniuses like Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk.

If AI ever achieves the goals of its proponents, Simon will get fatherhood honors, for he was its most adamant promoter. If it disrupts our world as much as some fear, it might be as significant as when Galileo insisted that the earth circles the sun and disrupted a cherished belief of Christianity. Simon was never imprisoned; but, worse, he was ridiculed.

Simon himself envisioned it when he wrote:

“The definition of man’s uniqueness has always formed the kernel of his cosmological and ethical systems. With Copernicus and Galileo, he ceased to be the species located at the center of the universe, attended by sun and stars. With Darwin, he ceased to be the species created and specially endowed by God with soul and reason. With Freud, he ceased to be the species whose behavior was—potentially—governable by rational mind. As we begin to produce mechanisms that think and learn, he has ceased to be the species uniquely capable of complex, intelligent manipulation of his environment.

I am confident that man will, as he has in the past, find a new way of describing his place in the universe—a way that will satisfy his needs for dignity and for purpose. But it will be a way as different from the present one as was the Copernican from the Ptolemaic.”

While this passage appears to show concern for humanity, I read it as Simon’s assertion that his work was as significant as Galileo’s, Darwin’s and Freud’s.

Simon also knew that credit for a discovery sometimes goes not to the discoverer but to whoever makes the most noise about it. Copernicus gave the definitive proof of heliocentrism, but he was stuck in Poland while Galileo told everyone in Rome.