Who are the preeminent individuals in American business history? A strong case might be made for a quintet: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, Bill Gates, John D. Rockefeller and Sam Walton. Who is primus inter pares? It’s Henry Ford in a walk-away.

Here’s why: Ford was an industrialist, inventor, aircraft pioneer, museum curator, horticulturist, labor progressive, racecar driver, philanthropist and, subtly and most importantly, a sociologist. This same man was a bitter opponent of organized labor, an anti-Semite, a mentally abusive father and a fickle autocrat.

Paradox entwined many aspects of Ford’s actions and personality. He was a shy man who reveled in the limelight; a reluctant philanthropist who, in order to avoid taxes, created the world’s largest foundation; and an early farmer who hated the drudgery of farm life. The paradoxes continue: Ford maintained a lifelong reverence for the rural life his Model T altered so completely; he said, “history is bunk” yet established Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum as living history; he was an indifferent manager who created the world’s largest privately owned enterprise; and finally, he was an industrial giant with a sweeping vision whose actions were all too often dictated by the narrowness and pettiness of a small man.

Farmer to mechanic

Henry Ford’s grandfather and father were of English stock and came to America via County Cork in 1847. They settled in southeastern Michigan near Dearborn. William Ford (1826-1905) married an orphan girl of Belgian descent, Mary Litogot O’Hern (1839–1876). The first surviving child, Henry Ford, was born in July 1863, the same month and year of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Ford’s schooling lasted from age 7 until 17. Like all farm children of the era, young Henry contributed meaningful work to the success of the family farm, but with no interest in the mind-numbing labor. However, simple mechanization was increasing farm productivity, and Ford fastened upon it. “I was a born mechanic,” he said. “My toys were tools, they still are.”

The year 1876 was tragic and pivotal for Henry Ford. His mother’s death loosened his ties to home, and a first inkling of the course of his life occurred that July. While traveling with his father in a wagon to Detroit, he beheld a self-propelled steam engine on its way to a threshing job. He jumped off the wagon and peppered the operator with questions. The machine’s stationary mode would have impressed Henry, but seeing it move under its own power was almost magical.

For his 13th birthday, he was given a watch. Fashioning his own crude tools, he took it apart and reassembled it, faster each time. He began repairing clocks and watches for free throughout the neighborhood. He later observed, “It is not possible to learn from a book how everything is made, and a real mechanic ought to know how everything is made. Machines are to a mechanic what books are to a writer.”

In December 1879, he left the farm and walked 10 miles to Detroit for a four-year mechanical apprenticeship at the James Flowers & Brothers machine shop for $2.50 a week. With a weekly boarding house bill of $3.50, he found extra work repairing watches for $2 a week. The proprietor moved the repair bench to a back room, concerned that customers might be scared off by Ford’s youth. After nine months with Flowers, he spent over two years in the engine works of the Detroit Dry Dock Company, learning about large machinery and motors. Long after, he regarded this as his fundamental apprenticeship.

Ford first met Clara Bryant (1866–1950) in 1885. She was the oldest of Melvin and Martha Bryant’s 10 children. Her father worked a 40-acre farm near Ford’s father’s farm. Henry and Clara were both serious and practical people. They married in 1888, creating a partnership in which Clara was a willing helpmate. Ford’s dreams of a self-propelled vehicle were yet nascent, but Clara had confidence in his fixity of purpose.

The marriage was given an economic basis through William Ford’s promised gift of a nearby 80-acre tract, half covered in timber. The elder Ford’s charge to his son was to clear and farm the land and it would be his. Henry set up a saw mill, selling lumber and financing a modest home for Clara and a small machine shop for his experiments. Ford accepted his father’s proposition “more because I wanted to experiment than because I wanted to farm.” In 1891, with the timber exhausted and the prospect of farming looming, Ford took a job with Detroit Edison. To further his experiments, he had to know electricity.

Ford’s antecedents

When the Fords moved to Detroit in 1891, automobiles were virtually non-existent in the U.S. By 1900, there were thousands, and the auto industrial age had arrived. To understand this decade of inflection, we must back up a bit. In 1877, August Otto obtained a patent on a four-cycle internal combustion engine, the seminal invention that laid the automotive industry’s foundation. Its basic features still undergird today’s gasoline engine, but it would be decades before the Otto engine would power the vehicles of Ford and his competitors. It was as big as a stove.

To the extent that there is an inventor of the automobile, credit must go to Gottlieb Daimler. Daimler built an Otto-type engine suitable as a power plant for an automobile. With a carburetor mixing nine parts gasoline to one part air, he substituted petroleum for synthetic gas. And by increasing the rpms, he lowered the weight-to-horsepower ratio to a modest 80 pounds per horsepower. “I have created the basis for an entire new industry,” he declared. Unfortunately though, Daimler focused on marine engines.

It was a French company, Panhard & Levassor, that steered automotive advancement back on the main road. The former wagon maker licensed the Daimler engine in 1889. By 1892, Panhard & Levassor vehicles rattled around the cobblestone streets of Paris—briefly the center of the automotive world.

Second only to the invention of the internal combustion engine in the development of the automobile was the advance of the bicycle industry. In a sense it constitutes the missing link between the horse and the automobile. The bicycle industry gave impetus to automotive advancement along two lines.

Henry Ford and other pioneers were influenced by the finely machined sprockets and gears coupled with metal hubs, spokes and pneumatic tires. Secondly, bicycle companies employed modern manufacturing methods in machining sub-assemblies and final assemblies that provided a template for automotive manufacturing. Henry Ford was an early American automotive pioneer, but the first were brothers Charles and Frank Duryea of Springfield, Mass. They made a successful run of the first gasoline automobile in September 1893. On a bitter cold Thanksgiving Day in 1895, with Frank at the wheel, a Duryea won a highly publicized 5.2-mile race from Chicago to Evanston, Ill., averaging 6.66 miles per hour. Literally and figuratively, the race for automotive leadership was on, and 32-year-old Henry Ford was well back in the pack.

The Quadricycle

Ford started at $45 per month at Detroit Edison, and within four years he was chief engineer, earning $1,900 a year. In 1893, the year their only son, Edsel, was born, the Fords moved again, to a home with a small out-building for Ford’s workshop. He attracted a small cadre of helpers who worked at Edison during the day and for Ford on nights and weekends. David M. Bell answered an Edison ad for a blacksmith. “What kind of blacksmith are you?” Bell answered, “A carriage blacksmith.” Ford with a faint smile replied, “Oh, a carriage blacksmith. You come to work.” Bell set to work nights and weekends on Ford’s project. Ford was no solitary inventor. He did little direct work himself, instead instructing and encouraging his four helpers—“try this, try that”—until his vision took final shape.

Ford aptly named his first vehicle the Quadricycle, bearing witness to the bicycle’s influence. Ignoring its complexity and originality, the quadricycle might crudely be described as a pair of bicycles lashed together with a motor in between. It ran on bicycle wheels with pneumatic tires. The Quadricycle was small, light and, at 500 pounds, the lightest vehicle yet. Light weight combined with engineered strength (through special steels) would be the hallmark of the famous Model T.

Early on June 4, 1896, Ford steered the little Quadricycle down Detroit’s Grand Avenue. Over the next two months he took it on test drives at every opportunity; breakdowns and other problems were Ford’s feedback for numerous improvements. Above all, he was a practical man, not an engineer or a theorist. Real problems required concrete solutions that steadily improved the article. It was kaizen (continuous improvement) before the Japanese coined the term.

Ford derived another benefit from driving around Detroit—attention. He loved the limelight, limited as it was then. Occasionally, he parked the car and hid behind nearby bushes to listen to the excited comments of the gathered crowd. In August of that fateful year, Ford was invited by his boss, Alex Dow, to the annual convention of the Edison Association in New York. Ford met Thomas Alva Edison and sketched out his concepts for the word-famous inventor. Edison slammed a dish-rattling fist on the table and declared, “Young man, that’s the thing! You have it. The self-contained unit carrying its own fuel with it! Keep at it.” Edison would become a close friend. Ford never lacked self confidence, but Edison’s praise heightened his optimism. Ford sold the Quadricycle for $200 and set to work on a new car.

Starting a business

The Quadricycle generated enough interest to enable Ford to attract backing for automotive manufacturing. In 1899, he amicably parted ways with Detroit Edison and concentrated on the Detroit Automotive Company. It was one thing to create the Quadricycle and quite another to field a commercially viable product. From 1899 to 1901, the Detroit Automobile Company produced 20 cars and then ground to a halt. Ford had turned decisively in a new direction: racing.

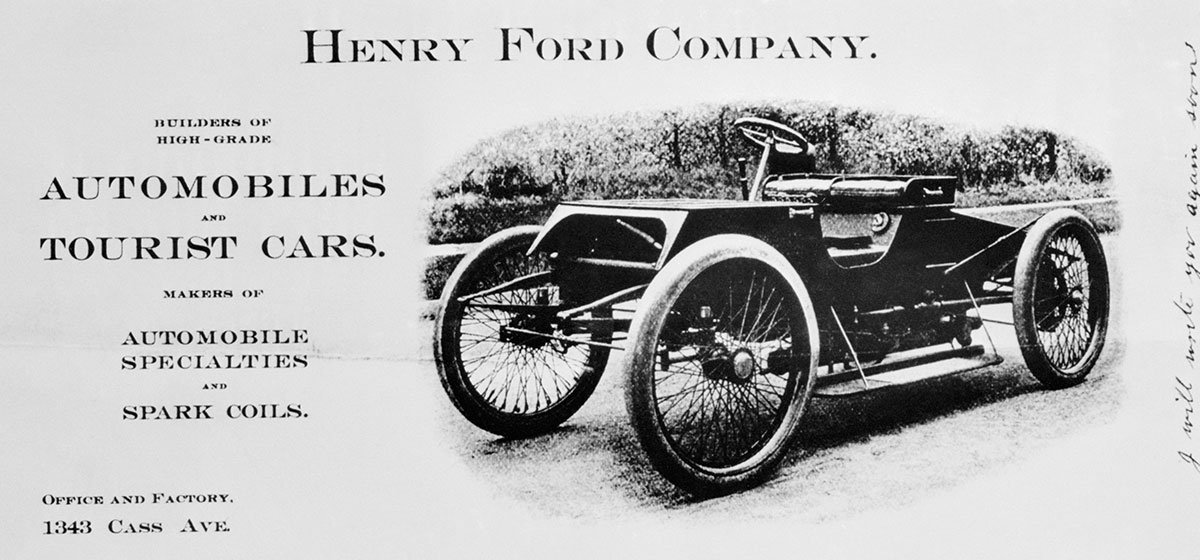

The 1,428-mile Tour de France Automobile race, first held in 1899, created a sensation in Europe and gave impetus to auto racing in America. Ford and his competitors knew that fame on the track would help sell cars. William H. Murphy, a wealthy lumber merchant and investor in Detroit Automotive Company, backed Ford in a new enterprise, The Henry Ford Company. It would build a racer and then capitalize on it with a line of commercial vehicles. Ford built the car and won a race against the formidable Alexander Winton of Cleveland. Ford’s win caught the eye of two prominent bicycle racers, Tom Cooper and Barney Oldfield.

Ford was now stuck on racing and was mule-headed in applying his talent to product development at the Henry Ford Company. Cooper, who had made money from his cycling career, backed Ford in building an advanced racer, the famed 999. So fearsome was this monster with its 10-foot wheel base and 7-inch cylinders that neither Ford nor Cooper found the courage to drive it. Oldfield agreed to drive the car, but there was a hitch—Oldfield had never driven an automobile. But with an ever-present cigar clenched in his teeth, the fearless Oldfield shrugged it off, saying, “I might as well be dead as dead broke.” Never slowing for turns, Oldfield lapped the field and went on to become America’s most famous racecar driver. He later reflected, “Ford and I made each other. Ford by making the car and me by driving it.” Then with a smile, he added, “but I did much the best job of it.”

Ford secured the backing of wealthy Detroit coal merchant Alexander Y. Malcomson for a third attempt at a commercially successful vehicle. Malcomson, 36, was captivated by both Ford and the seemingly limitless vistas of the young automotive industry; he was a plunger. Ford brought in a brilliant trained mechanic and practical metallurgist, C. Harold Wills, who would be involved in the design and engineering of every Ford vehicle through the Model T. During the winter of 1902, when Ford and Wills’s fingers numbed working in an unheated building, they would don boxing gloves and flail away at each other until the circulation returned. A skilled calligrapher, Wills designed Ford’s logo with the curlicue crosspiece on the F. It is still there today.

The Ford Motor Company

Malcomson was wealthy but overextended, and bankers were looking over his shoulder. Through a combination of Malcomson’s business connections and Ford’s fame for both automotive design and racing, they cobbled together a syndicate, raising $28,000. The Ford Motor Company was incorporated on June 13, 1903. Ford and Malcomson held the largest stakes, with 25 percent each. The company’s dazzling success rested on two remarkable partnerships. The first was between Ford and Wills and the second was with James C. Couzens. The Canadian-born Couzens was a blonde, stocky, belligerent-looking young man when he was seconded by Malcomson to the young Ford Motor Company. Couzens was Malcomson’s office manager and had initial doubts about the automotive flyer, but he soon fell under Ford’s spell. During his 12 years with Ford, the hard-as-nails Couzens built and ran the company.

The Ford Motor Company was able to launch a product on a miniscule $28,000 because it was strictly an assembler. Ford purchased the running gear, including the motor, frame, drive-train and axle as a unit delivered to the Mack Avenue plant, where a modest 40-man crew attached the body and wheels.

The running gear was manufactured by the Dodge brothers, among the most colorful of all automotive pioneers. John and Horace Dodge were red-haired, quick-tempered and argumentative—with others and themselves. They often relaxed by a hard night of drinking and the subsequent trashing of the unlucky watering hole. They were inseparable. Early in their careers, when asking for a job, they were told that there was room for one but not for both. John snapped back, “We’re brothers and we always work together. If you haven’t got room for two of us, neither will start. That’s that!” When success was but a twinkle in Ford’s eye, the Dodge brothers had a sizeable business with many established automobile manufacturers soliciting their capacity. But they, too, believed in Ford and, enticed by a 10 percent stake, committed to furnish 650 sets of running gear at $250 each. It was the best decision the cantankerous Dodge boys ever made.

Production started in June of 1903 and a steady flow of orders began in July. The Model A was a 1,250-pound runabout powered by a two-cylinder, eight-horsepower motor, which gave the car a top speed of 30 mph. It had the hallmark of all future Ford models. At $750, it was economical and reliable. Through March of 1904, on the sale of 650 units, Ford Motor made a profit of $98,851.

Ford’s explosive sales growth necessitated increased manufacturing space, and in early 1905 the company moved to a plant on Piquette Avenue with 10 times the space. Here the complementary roles of Ford and Couzens came into full flower. The demands of rapid growth put more immediate pressure on Couzens; he had direct responsibility for finance, accounting, sales, advertising, purchasing, and a host of sundry matters. His cramped outer office overflowed with vendors and prospective dealers entreating inclusion in the valued Ford franchise.

If you wanted to find Henry Ford, the last place you would look was in his dust-covered office. Ford pursued “management by walking around” before it became fashionable. He walked every inch of the floor—jesting, telling stories, and moving the humming operation forward by oblique directions: “I wonder if you could get this done right away. It would be fine if you could do” so and so. He knew everyone by name, and they called him Henry and Hank. Once there was a problem with mail. In search of an invoice, Couzens sent a clerk to ask Ford where it was. “It might be in my office,” was his response. The clerk found the invoice among 200 unopened letters on Ford’s desk. Reporting back to Couzens, the clerk was told, “Your job is now to open Mr. Ford’s mail.” Ford had his own way of dealing with Couzens’s insistence on orderly routine. Once when he asked for a part, he was told he had to sign a form. When he asked why, he was told that Mr. Couzens had initiated this procedure. Ford asked the young man to bring the several boxes of forms to him. Ford poured gasoline on the pile, tossed a match in it, and walked away smiling.

Seeing that the infant automotive business was likely to outshine his coal business, Malcomson told Ford he would like to send Couzens back to coal and assume his active position in the Ford Motor Company. Couzens was adamantly opposed, and Ford backed him to the hilt. Then the coal baron launched a heated policy debate in the boardroom. In 1903, cars costing less than $1,375 constituted two-thirds of the market. By 1907 the figures were reversed. Malcomson wanted to follow the direction of the market (it turned out to be a head fake) by producing a higher-priced car. Ford was determined to stake out a leading position in the low end of the market by producing one, and only one, model capable of sweeping the field.

The battle lines were drawn, with Malcomson on one side and Ford and Couzens on the other. Ford came up with an ingenious solution that cut the Gordian knot. He set about making Ford an integrated manufacturer, not an assembler. He established the Ford Manufacturing Company to produce the powertrain for the company’s low-cost model, excluding Malcomson, but giving the Dodge brothers equity. By adjusting the price paid to the Ford Manufacturing Company, profits could be dialed up or down in either company. Ford and Couzens assured the other shareholders that once Malcomson went away the companies would come back together. Foolishly, Malcomson became the principal backer of a completely new car company. Financially stretched and having no support on the Ford board, he sold his 25 percent interest to Ford for $175,000. It was a handsome gain, but in view of the halcyon days ahead, it was a pittance.

Ford now had 58 percent of the stock, Couzens had 11, and the Dodge brothers 10. From that day forward, management control was fused with ownership control. Ford was the absolute master of his enterprise, exercising far more power than Carnegie or Rockefeller.

The Model T

The Ford Model N, introduced in 1906, launched the Ford Motor Company on its path to dominance in the burgeoning automotive market. The Model N was a four-cylinder, 15-horsepower car, weighing 1,050 pounds and capable of 45 mph. At $600, it was “a car for the common man—absolutely guaranteed in every respect,” Ford said.

Ford sold 8,423 vehicles in that selling year, compared with 1,599 a year earlier. Profits rose $100,000 to $1 million. The company offered higher-priced body styles R and S, but all built on the same platform. The common platform was the key. Through the use of a single chassis, Ford could avoid the curse of the annual model change—new tooling and interrupted production.

The Model N’s stunning success precipitated a radical change in Ford’s manufacturing. The company moved to a vastly larger plant at Highland Park in northern Detroit. Production had now grown beyond Ford’s management capabilities. Walter E. Flanders, a flinty Vermonter and self-educated machine-tool expert, joined. Under Flanders, batteries of high-speed machine tools and grinders manufactured tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands of precision machine parts assured to feed the voracious maw of demand. Years later, reflecting back on what all this meant, Henry Ford observed, “Our policy is to reduce the price, extend the operations and improve the article. You will notice that the reduction of the price comes first. We have never considered any cost as fixed.”

As Ford needed Flanders, Couzens needed Norval Hawkins. Hawkins’s accounting firm had audited Ford and was familiar with its operations. A strong salesman, Hawkins’s greatest strength was his orderly managerial mind. This facilitated a working relationship with the hyper-demanding Couzens. Hawkins organized the dense network of dealers throughout the U.S. and later the world. He relentlessly reduced the size of dealers’ territory to force more intensive cultivation of a smaller customer base. Hard-hitting ads drove home the case for the Model N: “Not one agent in 10 took on the Ford line willingly. His customers forced it” and “since the agents’ profit is so small, the buyer must be getting pretty nearly ‘all automobile’ for his $600.”

Even as sales for the Model N were ramping, Ford began work on his masterpiece, the Model T. The birthing room was a walled-off, restricted space, 12 feet by 15 feet on the third floor of the Piquette Avenue plant. Working with Ford was his alter ego, Wills, and a handful of confidants, including Charles Sorenson, a Danish patternmaker hired in 1905. Over a 40-year career, “Cast Iron Charlie” would become the most powerful man in the organization next to Ford. He got his start by taking Ford’s ideas and sketches and then making wooden patterns and finally parts. Ford never relied on blueprints (there was question as to whether he could read them). He was a “cut and fit man”; once he saw the part, he knew it was right or knew how it needed to be changed. On the Model T, Ford possessed almost a divine insight; at every fork in the road he instinctively took the right path. At the core of the many advances in the Model T lay vanadium steel. This permitted the tensile strength of crankshafts, axles and gears to be more than doubled, halving the weight of the part. The Model T sat high on the road. It was designed to take a beating over country roads that hardly merited the name. It was light, powerful and durable.

Demand for the Model T was simply inexhaustible. Sales rose from 10,607 in 1909 to 472,350 in 1916. From 1908 to 1916, company sales rose from $9 million to $207 million and profits jumped from $1 million to $57 million. By 1927, its last year of production, total sales of the Model T exceeded 15,000,000. It was the greatest product in automotive history.

It was in 1913, with production climbing toward 200,000 units at the Highland Park plant, that mass production and the assembly line came of age. Contrary to legend, Ford did not invent the assembly line. Rather, it developed in response to the insatiable demand for the Model T; it bubbled up from the bottom. Assembly line mass production is like a river system, with rivulets of small components assembled into larger subcomponents, such as motors and axles, finally all coming together. The complexity was staggering. In 1914 there were 15,000 machine tools at Highland Park. Parts had to be produced accurately and quickly, and then subassemblies were fed into and synchronized with the entire system. Like so much with Ford, it was cut and fit, trial and error. The automotive industry and others soon adopted assembly line mass production that first saw the light of day at Highland Park. The fame of this American production miracle soon spread around the world. It was given a name: Fordism.

The $5 day

On Sunday, Jan. 5, 1914, Ford gathered a small group in his office, including Couzens, Hawkins, Sorensen and Wills. Budget estimates for wages, production and profits were written on a blackboard; Sorensen acted as scribe. Model T production was projected at 250,000 units. Ford called attention to what he perceived to be an imbalance between wages and profits. He then instructed Sorensen to plug in higher daily wage minimums, thus shifting dollars from the profit column to the wage column. Beginning at $2, the numbers moved up steadily in 25-cent increments. Finally, when Sorenson chalked $5 on the board, Ford jumped up: “Stop it Charlie, it’s all settled. Five dollars a day minimum wage at once.” Thus began the famous $5 day.

The following Monday, with drums pounding and trumpets blaring, the crude rhetorical flourishes of the announcement read: “The greatest and most successful automobile company in the world would inaugurate the greatest revolution in the matter of rewards for its workers ever known to the industrial world.” The $5 day made Ford one of the world’s most famous men. It was not charity, nor was it a snap decision. The size of the future automotive market was like the monster out in the forest. Ford perceived its immensity. For Ford, wages and profits were not the zero sum game that Frick and Carnegie made them in the steel industry. The Model T was built so anybody could drive it, Ford mass production made it universally available, and the $5 day meant everyone could afford it. The next seven years perfectly validated Ford’s vision and methods. By 1921, Ford produced over a million units with profits of $75 million. At the same time, wages rose and Model T prices plummeted to $285.

Ford established the “Sociology Department” to insure that Ford employees would put their increased income to good use. Each investigator was assigned 727 employees and made 15 “house calls” a day. The questions were deep and probing. Was the home adequate and well kept? Was the diet healthy? Were family finances in order? Was English spoken at home? To increase English proficiency, an English school was established. Looking ahead to future Ford employees, the Henry Ford Trade School flourished throughout Ford’s lifetime. The hiring policies of the Ford Motor Company were cutting-edge for their day. Special efforts were made to hire the handicapped, ex-convicts, and a growing number of blacks migrating to Detroit.

None of those present on that Sunday in 1914 could have known it, but that day marked the apogee of Henry Ford’s career. He was 50 and would live another 33 years, but his great creative work was behind him. He would become immensely richer, and Ford Motor Company would become a globe-girdling enterprise. Increased fame would carry Ford to mythical status. But from here on, it was a long downhill slide on a gentle slope.

Total control

During the five years after 1914, as Ford Motor Company profits soared from $25 million to $70 million and as fame made him a world figure, Henry Ford changed. A series of key departures removed any counterbalance to his absolute power. Although remaining a director until 1919, Couzens resigned in 1916. Wealthy and politically ambitious, he went on to be mayor of Detroit and a U.S. senator.

The Dodge brothers did not go quietly. With Highland Park bulging at the seams, Ford began to plan the huge River Rouge complex. At the same time he cut the price of the Model T to $360. To finance all this, Ford planned to pay only nominal dividends. John Dodge exploded. In 1913 the Dodge brothers had begun to manufacture automobiles in a price range above the Model T. They were heavily reliant on their dividends from Ford. The Model T price reduction was the crowning blow. It would sap Ford’s profits by $40 million; Dodge said Ford might as well have burned the money. A court trial ensued.

On the stand Ford said he was embarrassed by the “awful profits; we don’t seem to be able to keep the profits down.” Plaintiff’s counsel: “What is the Ford Motor Company organized for except profits, will you tell me Mr. Ford?” Ford: “Organized to do as much good as we can everywhere for everybody concerned.” It was pure Ford—right from the heart. The Dodge brothers won the suit, dividends were paid and Ford moved immediately to Plan B. For the first and only time in his life, Ford secured a line of credit to buy out his partners. Couzens received $29 million and the Dodge brothers $25 million—a handsome return on their 1903 investment of $10,000. They would not live long enough to enjoy it. The inseparable brothers died months apart in 1920. In addition to Couzens and the Dodge brothers, Harold Wills and Norval Hawkins joined the exodus. Henry Ford was alone. John D. Rockefeller at his peak owned 2/7ths of the Standard Oil Company. Henry and his son Edsel Ford now owned 100 percent of the Ford Motor Company.

On a broader stage

Ford’s public embarrassments began with the “peace ship.” Flush with worldwide fame and his growing fortune, Ford undertook the Herculean task of bringing peace to the warring nations of Europe. In November 1915 he chartered the Scandinavian liner Oscar II in order to fill it with pacifists of every stripe, including Hull House’s Jane Addams, department store magnate John Wanamaker, and his friend Edison. Naively, Ford sought government sponsorship, and toward that end arranged a meeting with President Wilson. Oblivious to White House protocol, Ford plunked down in an armchair without being asked, his leg dangling over the arm of the chair. He pressed his case, and the president turned him down. The luminaries never showed, and Ford got sick and left the ship in Norway. The press pilloried the peace ship from the start, labeling it the “Quixotic project of a country bumpkin.” When told the cost totaled $465,000, Ford reposted, “well, we got a million dollars advertising out of it and a helluva lot of experience.” If the peace ship didn’t break the back of Ford’s desire for a public persona, subsequent events did.

Facing a tight congressional campaign in 1918, Woodrow Wilson convinced Ford to run for the U.S. Senate. He lost, although by less than 5,000 votes.

In 1916, the Chicago Tribune’s colorful owner, Colonel Robert McCormick, labeled Ford an anarchist. Ford filed suit for libel. The case came to trial in Mount Clemens, Mich. in May 1919. Hundreds of attorneys, reporters and sundry retainers representing the armed camps of Ford and McCormick jammed into the sleepy town. The circus atmosphere nearly rivaled the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tenn. From the beginning, Ford was his own worst enemy. He and his attorneys let the McCormick legal team shift the focal point of the trial from Ford’s alleged anarchy to his views on America. It was role reversal; Henry Ford, not the Chicago Tribune, was on trial. On the stand, Ford was grilled. His limited education and narrow focus left him an easy mark. When asked “Who was Benedict Arnold?,” Ford replied, “He is a writer, I think.” When his own counsel objected to a question, Ford brushed him aside and answered an unfair question the judge was prepared to overrule. Ford won the trial and was awarded six cents. His honesty and sincerity made him the laughing stock of the intelligentsia but endeared him to the majority of Americans.

The darkest chapter of Ford’s public activities came with his weekly paper, The Dearborn Independent (1919–1930). Each issue contained “Mr. Ford’s” own page, ghostwritten by William J. Cameron. “The International Jew: The World’s Problem” blared on the May 1920 cover of The Independent. What brought on this insanity? Sensationalism was to be the cure for flaccid circulation. Again, in 1924 and 1925, The Independent published a series of anti-Semitic articles on the prominent Chicago attorney, Aaron Sapiro. He sued, Ford apologized and settled. But the damage was done. The only half-hearted defense of Ford’s mis-behavior is that it was done more out of ignorance than malice. After 15 years of failed attempts to give voice to his philosophy, he retreated into domestic isolation at his Dearborn residence, Fairlane. During the last 20 years of his life, Ford contented himself with random acts of intervention at the Ford Motor Company. He damaged it, but could not destroy it.

Ford’s more successful extra-automotive activities during the 1920s bear witness to the fertility, boldness and surprising flexibility of his mind. He began by taking over a struggling local aircraft builder. The company needed an airfield. When told by his advisor, Ernest Liebold that the site had been developed at some expense for a housing subdivision, Ford rejoined, “Oh, Liebold, maybe it was a subdivision yesterday, but it is a landing field today.” In 1926 Ford built the famous Ford Trimotor, the largest commercial aircraft then produced in the U.S. It had a wingspan of 70 feet and carried eight passengers. Production peaked in 1929 with 86 planes. Ford organized his own airline with service to Chicago, Cleveland and Buffalo. Planes were sold to the Army and Navy as well as Pan American, Northwest and TWA. When the Depression cramped automotive profits, Ford folded his aircraft operations. The Ford Trimotor did not become the Model T of airplanes—that honor belongs to Donald Douglas Sr. and the legendary DC3. But today the Ford Motor Trimotor that carried Admiral Byrd to the South Pole hangs proudly in the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum with the Spirit of St. Louis and the Wright “Flyer.”

In 1929, Ford set about to discover a versatile and nutritious crop to rival wheat, corn and rice. He chose the soybean and backed the experiments of the famous black scientist George Washington Carver. Ford technicians developed a process for extracting oil from soybeans. It was used for the manufacture of all Ford paint and for plastic components. Today, the soybean is the world’s fourth largest crop. In 1920, Ford bought the Detroit & Ironton Railroad. Perplexed by the high cost of roadbed maintenance, Ford suggested substituting steel crossties embedded in concrete for traditional wood ties and gravel roadbeds. He was told by his engineers that harmonic vibrations would crack the concrete. Ford said, “Has anybody tried it?” The experts said nobody ever had; their engineering calculations pronounced definitively on the subject. Ford: “Then go ahead and lay down a thousand feet and let me know what happens.” As predicted, the concrete cracked, the ties dislodged and the engine derailed. Ford: “Anybody hurt?” Answer: No. Ford: “Good, now we know it doesn’t work.” It was vintage Ford.

Edsel Ford became president of the Ford Motor Company in 1919. At his father’s urging, he had skipped college and begun his career at the company in 1912. The tragedy of Edsel Ford is mirrored by the rise of Charles E. Sorenson, whose success paralleled the construction of his giant River Rouge complex. On its 2,000 acres were coke batteries, blast furnaces, and foundries, along with glass and tire manufacturing. Rouge grew to become the world’s largest manufacturing complex. Sorenson was its lord and master; he was 11 years older than Edsel and 18 years younger than Henry Ford. He was at the same time a mentor to Edsel and a second son to Ford. He was, in effect, the son that Ford wished Edsel to be. Edsel was an obedient son and an able manager. Given the opportunity, he might have built a competent team capable of moving the Ford Motor Company from one-man rule to a professionally managed organization. In the mid-20s, Ford told Sorenson and others that Edsel, not he, would be running the company. Instead, he often undercut Edsel in the most demeaning way. For instance, Edsel with due consultation authorized the construction of a battery of coke ovens. Ford then confided to one of his henchmen, “As soon as Edsel gets those ovens built I’m going to tear them down.” Edsel died in 1943, ostensibly of stomach cancer, but perhaps more of a broken heart.

Following Edsel’s death, Henry Ford resumed presidency of the company before being succeeded by his grandson, Henry Ford II, in 1945.

Henry Ford died of cerebral hemorrhage on April 7, 1947. By the terms of his will, his Ford ownership was divided into Class A (non-voting) stock and Class B (voting) stock. The charitable Ford Foundation, charterd by Henry and Edsel in 1936, held 90 percent ownership, while Edsel’s widow, Eleanor, and her four children held voting control through their 10 percent ownership of the B shares. To this day, Ford is still the largest family-controlled company in the world.

The bottom line

Save for the Gutenberg printing press, the automobile has had more impact on society than any other invention. And Ford’s influence was far greater than all his automotive contemporaries combined. But the creation of the mass-produced Model T was only the foundation upon which rested the towering Ford legend.

A 1922 ad carried a message from Henry Ford: “Buy a Ford and spend the difference.” Not save, but spend. By reducing the price, increasing the market, and raising wages, Ford made the automobile the ultimate consumer product. This was strikingly original, and Ford pushed his thinking further. Despite the creation of the Ford Foundation and considerable charitable giving, Ford really didn’t believe in charity—and said so. Profits were not to go to charity but toward constant and insatiable reinvestment in the business, creating more and better products and jobs. He regarded his business as a semi-public entity. Thus, like a heavy-footed driver running a stop sign, Ford on his journey from agrarian America sped through industrial capitalism directly into consumption society and the age of social responsibility. But this journey brought with it the growth of shallow materialism and a declining work ethic. This disquieted Ford, and he unfairly identified Edsel and his fancy Grosse Pointe friends with these deficiencies. When he sent his minions to destroy Edsel’s coke ovens, he was lashing out at his son for his role in a world that he neither understood nor wanted.

Henry Ford played an active role in the creation of his own legend. He was the first celebrity businessman. His many faults were written in bold letters. How did grassroots America vote? Over a period of 25 years, Henry Ford received 300–700 personal letters a day, millions in all. Henry Ford wrapped his slender fingers around the heartstrings of America as no one before or since.